Driving through my hometown of Jacksonville in East Texas one warm spring day, I decided to detour along Lincoln Street and tour the old neighborhood I visited so often during my childhood in the mid-70s. I was glad to see that one of my favorite spots remained. Back then, we’d called it Miss Melvin’s Place. Now, it was freshly painted, with a new sign that read Sylvia Mae’s Soul Food, and the parking lot was full. The owner must’ve passed Daddy’s test.

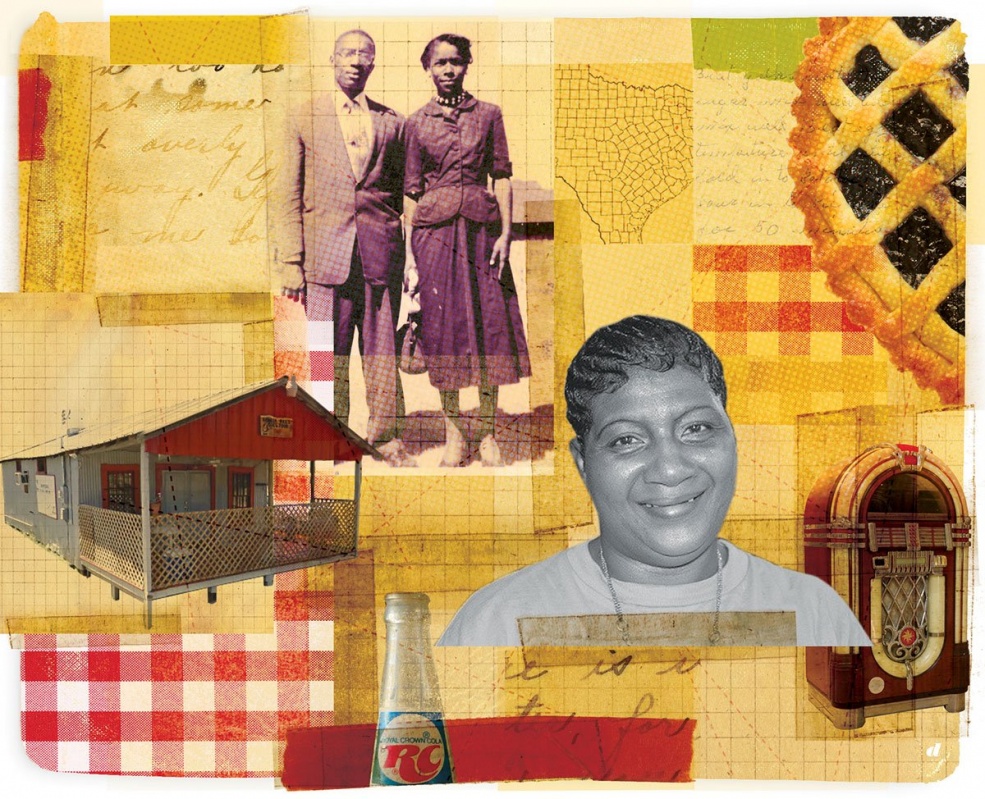

Back during the segregation era, Lincoln Street was typically bustling. On weekends, it was called the “red-light district,” says my 92-year-old mother, Connie Nays. “Paycheck money could be spent on gambling, jumping juke joints, bootleg whiskey and other cash-flowing businesses.” Good eating places were all around, and one was Miss Melvin’s. There was no sign out front, and it sold fish sandwiches and plate lunches.

Tapping my brakes that spring day of my return visit, I was amazed at how the landscape along the street had changed. The businesses had included the general store, the café/pool hall, the drugstore and others, as well as Mr. Polk, who parked his “cab” beside the café to wait for folks who needed a ride.

Now, the street looked like a tornado had swept through and taken away most of the buildings. It made me feel sad.

The change was an unintended effect of integration, after which everyone’s green money was good everywhere. There was no longer a need for anyone to go to the back of a café to order a hamburger. Once anyone could go anywhere to get what they needed, business thinned out in the neighborhood.

Now there are mostly vacant lots, but I was glad to see a new brick church with flashing neon lights, and a brick building with three tenants, including an insurance agent and a beauty shop.

As I approached the next corner, my heart pounded as I saw the building I remembered from my youth, now with a blinking sign that said “Open.” I pulled into the still-red-dirt parking lot and reflected on my memories of the busy café.

I was an energetic teenager, raised on a farm outside of Jacksonville. To beat the summer heat, we started our mornings before daybreak. Monday though Friday, my mom cooked a hearty breakfast. After eating, we put on our hats and cool cotton clothing and prepared to select the best vegetables we’d raised for sale. We kept the bruised or overripe vegetables for eating and canning at home.

Saturdays were different. We got to go to town, and my sister and I would ask our parents for money to get a golden-fried fish sandwich. When we entered Miss Melvin’s, we knew we would see a crowd of characters from the community.

The screen door’s slam announced customers coming in or going out. I’d immediately notice the bright lights flashing on the jukebox. Usually it was playing a blues song. Passing by the red-topped tables with mismatched chairs, my sister and I headed to the bar because sitting at the bar made me feel grown-up.

There were always a few people waiting and a few people eating, and there was a freedom feeling in the place, like when the teacher leaves the room. I inhaled the mingled aromas of fish and cigarette smoke. Talk was punctuated with bursts of laughter, and all competed with the song from the jukebox.

Someone would always yell, “That’s my song!”

Dad gave us $5 to share since he had to buy gas to drive home. “Two sandwiches. To go,” I told the waitress, side-glancing at my sister. I knew it would be a long wait because the cook didn’t start any order until you placed it. And she used a cast-iron skillet, not a deep fryer. From the bar, I could see her turning and fixing things through the kitchen door.

When I asked about the drinks, I was told that they only had Pepsi, RC Cola and water. No NuGrape or Fanta orange? I sighed, because our parents forbade brown sodas. So I ordered water.

Our food came out smoking hot and sacked to go, but I couldn’t wait. I signaled my sister to sit down, and it became an “eat here” order.

After observing the various customers and how the waitress handled them all, I just wished I had more money so I could leave her and the cook a good tip.

Now, as I opened the door of my car, I wondered how Miss Melvin’s had changed. I entered to check out the food and service of the new owner.

From segregation. To integration. To modernization.

As I entered the café, all races were dining together. The menu included down-home cooking such as meatloaf, chicken and dressing, oxtails, smothered pig feet and, of course, fried fish. The new owner, Sylvia, had posted blue “Like us on Facebook” signs on the tables.

The place still seemed small and cozy. Sylvia made me feel like I had just walked into her kitchen and sat down. In a few minutes, she brought me my plate. The macaroni and melting cheese, fresh purple hull peas and hot-water cornbread were delicious. It looked like the building still holds cooks and owners who passed the test Daddy always gave us kids.

My daddy would gather his unsold vegetables from the farmers market, and then we’d sell them up and down the streets. I’d help work with the customers. He always reminded us that customer service is just as important as the product. Daddy would say, “Now listen, chirren: You may have only one chance to keep a customer.” Then he would watch to see how we handled customers. That was our test.

After cleaning my plate and finishing off my unsweetened tea at Sylvia Mae’s, I left satisfied. I had entered wondering: Which would win this time, customer service or the product? I’ve found, even in changing times, it takes both.

——————–

Cynthia Matlock manages a small cattle ranch outside of Whitehouse with her husband.