Let me begin with a story from 1963, when we were seniors at Austin High—two couples looking for something different to do on a summer night. We drove out U.S. 183 toward Burnet and came upon the Hilltop Inn, all lit up with lots of cars and trucks parked outside.

The people inside—the picture is etched in my mind—were dancing. There were couples, but there were also women with women and children with children. Some women were—I swear—wearing gingham dresses and bonnets.

A man inside stepped in front of us. He looked us up and down. We were wearing shorts, and not just any shorts but the newest rage, madras plaid shorts. He said, “You’re not welcome here,” and shut the door.

We had stepped into the world of the cedar choppers. Decades later, I would spend about five years researching the history of this community for my book, The Cedar Choppers: Life on the Edge of Nothing.

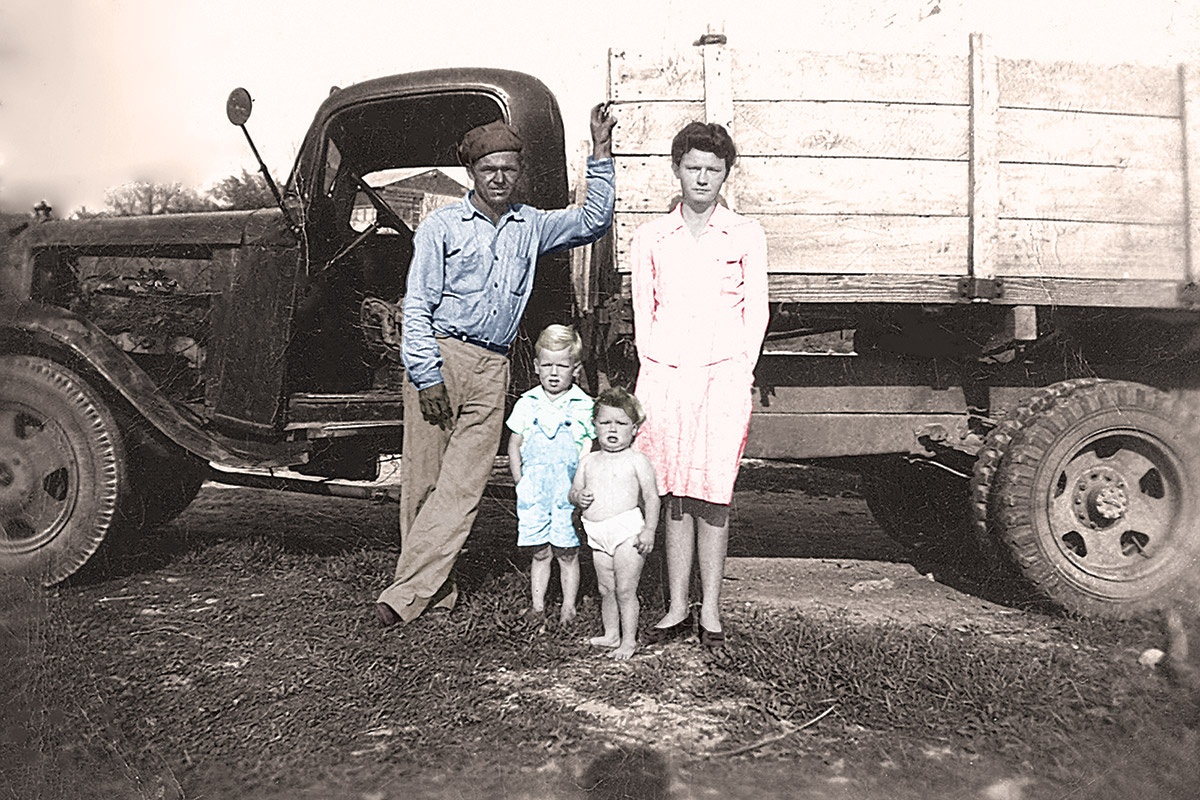

The cedar choppers were descendants of Scots-Irish immigrants who had migrated from the hills of Appalachia after the Civil War. They replicated their Appalachian way of life in the cedar brakes of the Texas Hill Country, where they raised large families in shabby housing without plumbing and survived by growing some corn, raising some stock, hunting, making moonshine and turning cedar into charcoal and posts.

When the agricultural economy of the South crashed during the Depression and farmers left in droves, this lifestyle enabled them to hang on. As late as 1941, an Austinite could still marvel that “within sight of the Capitol dome live mountaineers who speak a dialect and get their water from springs,” according to a passage in the book Texian Stomping Grounds.

Mountain cedar (Ashe juniper) had always been valuable because it has a heart of dark, oil-permeated wood that lasts for decades. When farms were turned to pasture after World War II, the demand for cedar fence posts soared. With nothing but an old truck and an ax, a man could make as much money in two days cutting cedar as a week working in one of the local quarries.

Cedar choppers were some of the most independent laborers in America: They had no boss, no land to farm, and they could sell their cedar anywhere. They took orders from nobody, accepting the money society offered but rejecting its routines. Their defining characteristics became fierce independence and a combative directness in dealing with the outside world.

The emergence of Austin as a metropolitan area brought cedar choppers and their coarse ways into stark contrast with the genteel urban population. “Cedar chopper” became a pejorative term, like Okie in California. Strong as they were from cutting cedar with an ax, they didn’t hesitate to fight back. Frank Wilson, who knew cedar chopper families, said in a 1978 interview at the Austin History Center, “They were very independent and very proud people—and aggressive, very aggressive.” This clash of cultures became the story I wanted to tell.

My first interview was with Ronnie Roberts, who as a kid had loaded cedar onto trucks at his grandparents’ yard in Oak Hill, then a community southwest of Austin. He told me that his father, grandfather and great-grandfather had all been cedar choppers, living along Barton Creek, west of Austin. His dad owned a cedar yard outside Kerrville and was an upstanding citizen and a deacon of the church. But Ronnie’s older brother died at 6 of a brain tumor, and things fell apart. His dad started drinking, and his mom committed suicide. In 1958, Ronnie and his three sisters moved in with their grandparents at the cedar yard.

I was stunned by his honesty and by the responsibility of telling his and other stories—not in generalities but as actual events in the lives of people whose parents, grandparents and great-grandparents had grown up in the hills, worked together, intermarried and raised families. To have a chance of understanding them, I knew I had to know these connections. I had to create a big family tree. By the time I finished over a year later, it encompassed more than 2,500 related individuals and demonstrated that most of the cedar choppers in the Hill Country counties were kin to one another.

As I got to know them better, I became more direct as I gathered oral histories. I asked Alice Patterson, “Did y’all ever feel, when you went into Austin, that some of the people in Austin kind of looked down at you as country folk?”

She replied, “You know what? It didn’t bother me. They do. They did.”

“They did?”

“Yeah, they did. And I didn’t know it.”

I asked Don Simons, “How did you guys feel when you came into town and you saw these nice green lawns, and these guys walking around with their white golf shoes on. What did you think about that?”

“Terrible,” he replied. “When you didn’t have no shoes. And the end of your toes were bloody because you stubbed them on the rocks. You felt terrible because people looked at you. They don’t know how to deal with you. Very degrading.”

They wanted to talk about their lives and share the uniqueness of their upbringing and what it was like to grow up working in the brakes. They were proud of their fortitude and far enough from some of the painful aspects that they could talk openly.

The heyday of the cedar choppers that began in the 1940s ended abruptly with the introduction of steel fence posts in the 1960s, but the story lives on.

Ken Roberts, a member of Pedernales EC, has lived on a ranch outside Liberty Hill for the past 45 years. He retired as a professor from Southwestern University, where he researched the effects of economic change on rural people in Mexico and China. Contact him at thecedarchoppers.com.