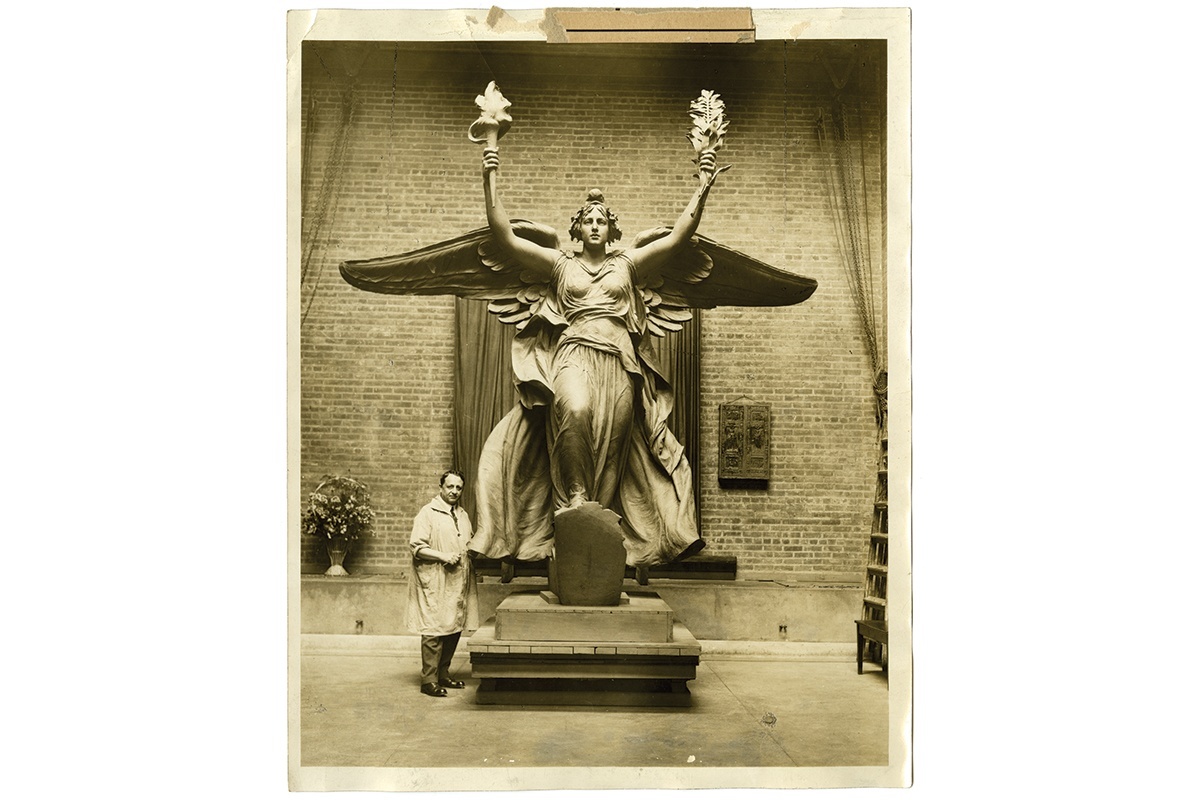

Pompeo Coppini may be the unluckiest sculptor in the history of Texas. The Italian-born artist first came to Texas in 1901 and worked here until his death in San Antonio in 1957. His heroic bronze figures are scattered all over the state, from his Terry’s Texas Rangers monument on the Capitol grounds in Austin to his John H. Reagan memorial in Palestine and his Charles Noyes Memorial in Ballinger. He is considered Texas’ foremost sculptor.

But Coppini saw one of his early works, a statue of George Washington commissioned by Mexico City in 1910, toppled from its pedestal and dragged through the streets of the city by an anti-American mob in 1914. His largest and most visible work, the Littlefield Fountain at the University of Texas at Austin, was curtailed by the university’s board of regents, which removed two large obelisks from the design, then dismembered by the university’s architect, Paul Cret, who distributed six statues intended for the fountain along the campus’ South Mall, turning them, Coppini complained, into “mere decorations.” The university has subsequently removed all six statues, consigning five of them to storage and moving the sixth, portraying Jefferson Davis, to the Briscoe Center for American History.

Coppini’s design for his other major work, the Alamo Cenotaph, was mucked about with in a similar fashion. Coppini envisioned a granite monument with a 60-foot-high shaft rising from a 40-foot-long base that would support two symbolic female bronze figures, the Spirit of Sacrifice and the Spirit of Texas, as well as bronze figures of Travis, Bowie, Crockett and Bonham. The committee that commissioned the monument decided that both the monument and the figures should be marble, a material that Coppini felt would not hold up well in the Texas climate. It has not.

Not everyone liked Coppini’s work. Folklorist J. Frank Dobie was his severest critic. Dobie said he hated the Littlefield Fountain and during World War II suggested that the university should contribute it to the national scrap metal drive. When the Alamo Cenotaph was dedicated, Dobie wrote that it looked like a grain elevator and that Coppini had sculpted Travis, Crockett, Bowie and Bonham in poses that made them look “as though they had come to the Alamo to have their pictures taken.”

After the 1900 Galveston hurricane, which killed 6,000 people, the city fathers commissioned Coppini to create a monument to the victims. Coppini showed them a 10-foot-high plaster cast of his proposed monument, depicting a grieving mother in the midst of the storm pressing an infant to her breast while a small child clings to her skirt. The committee thought that it was too heart-wrenching and rejected it. It was never cast in bronze. Coppini attempted to exhibit the plaster cast at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, but somehow its crate was misdirected, and the cast never made it into the main statuary exhibition hall.

In 1914, Coppini donated the cast of the proposed Galveston monument to UT along with 23 other plaster casts of his work. The university managed to lose all 24 casts. The collection was briefly exhibited in 1919, and no one has seen it since. During his lifetime, Coppini frequently questioned the university about it and never received a satisfactory answer.

Coppini was unlucky even when he was lucky. His Charles Noyes Memorial, considered one of his most moving and poignant works, is on the courthouse square in Ballinger. It depicts a young cowboy standing affectionately by his horse. The cowboy is Charles Noyes, the only son of a wealthy local rancher, who was killed in a fall from his favorite horse. The statue was commissioned by Noyes’ grieving parents in 1919, a low point in Coppini’s career and in his finances.

He intended to ask the Noyeses $25,000 for his work, but when he traveled to Ballinger to meet with them, he was so moved by their grief and their modest style of living that he told Mr. Noyes that he would do it for $18,000. “I was prepared to pay twice that,” Noyes told him.

Texas novelist Stephen Harrigan was so intrigued by the Ballinger statue and the story behind it that he used it as the plot of his novel Remember Ben Clayton. That novel may be Coppini’s greatest legacy to Texas.

A version of this article appeared in Lonn Taylor’s Rambling Boy column in the Big Bend Sentinel in Marfa, September 13, 2018. Taylor, former historian at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, lives in Fort Davis.