Robert Hinkle likes to sit where he can see everyone in the room and who’s walking through the door. He leads me to the corner of a long table at the back of a pandemic-emptied Masonic Lodge in Leander and chooses a seat with a clear view of the entrance.

He wears an Air Force cap and a sky-blue Mason’s shirt embroidered with “N. Hollywood,” each emblematic of the twists and turns of his prolific career.

Attention to wardrobe figured into Hinkle’s duties as unofficial technical adviser on the West Texas and Panhandle sets of Giant and Hud, two better-known entries in the catalog of midcentury Texas cinema. When costume design choices went awry—a hat that wasn’t creased correctly or was impractical for work, jeans too short for horseback riding—he would issue a concise verdict: “A Texan wouldn’t wear that,” then figure out a fix.

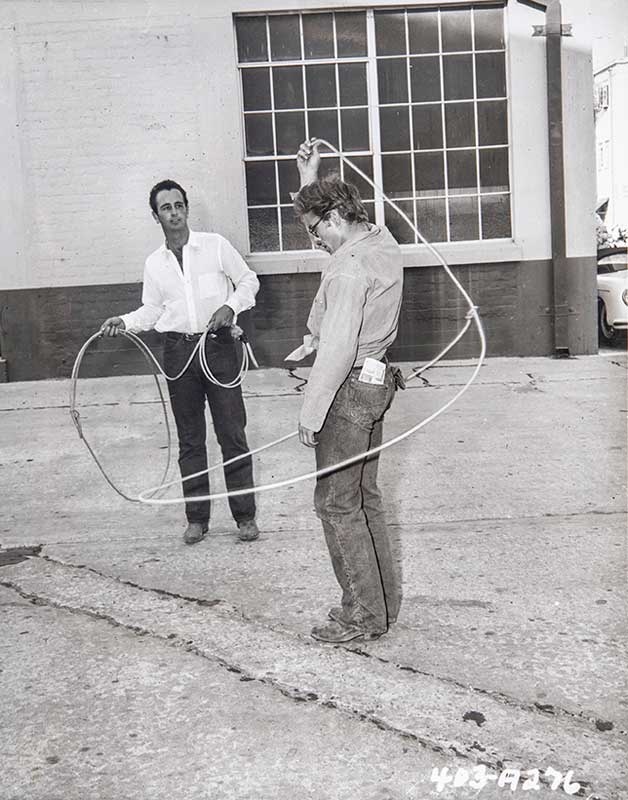

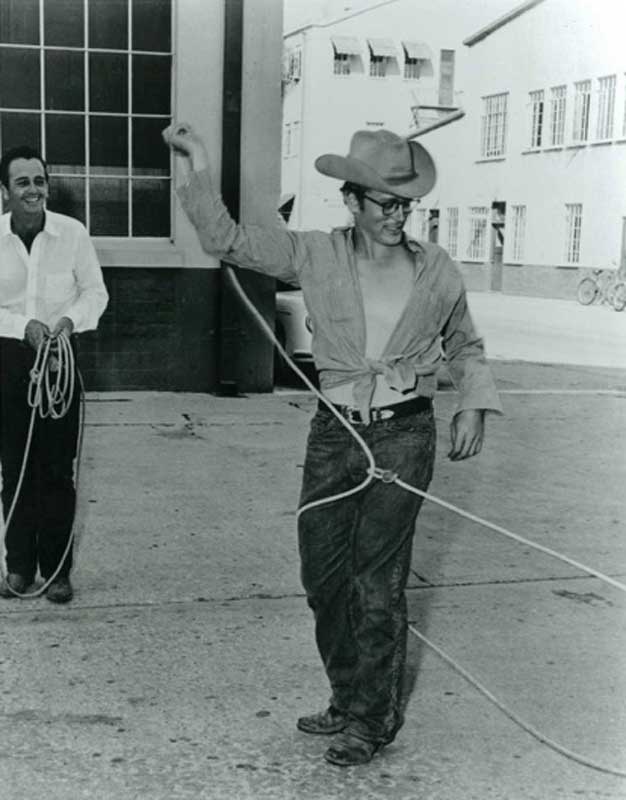

Hinkle lassos Elizabeth Taylor on the set of Giant.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

That was just one duty on two projects over an entertainment career that spanned decades and comprised a raft of roles: stuntman, actor, writer, producer, director and Texas talk man, as Giant director George Stevens dubbed him.

Hinkle’s preference for an unobstructed view isn’t surprising, either. A few years before he coached Hollywood luminaries Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman on the nuances of a type of Texas dialect—leaving the “g” off words like “walking” and emphasizing r’s when they ended a word such as “mother” or “father”—he enjoyed an embarrassment of bird’s-eye views.

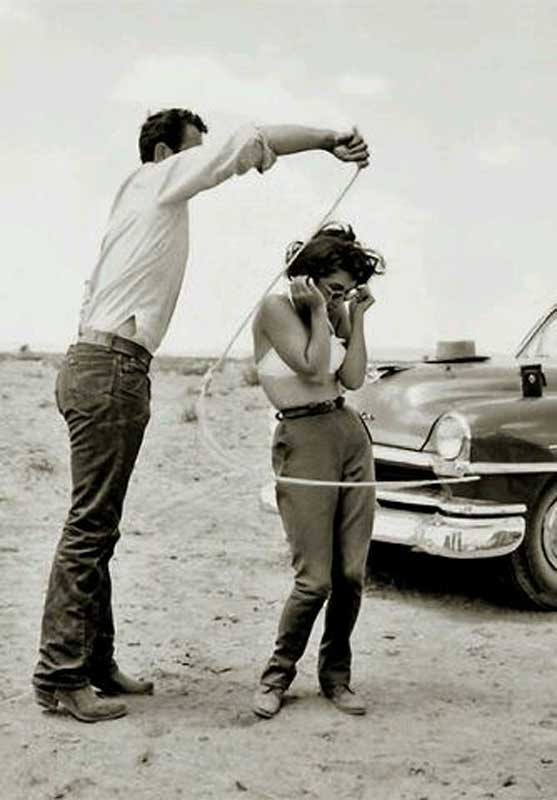

James Dean shows Hinkle how well he’s learned to hogtie.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

Born and raised in the South Plains of Texas, Hinkle left high school in 1947 to join the Air Force at 17 after securing a promise from a recruiter that he could continue his education while enlisted. “Nobody in my family ever had a high school diploma,” he says. After earning that credential, he spent several months in Europe working on a crew that flew coal from Frankfurt to Berlin.

On one trip, the co-pilot had a heart attack midflight. Hinkle took over co-pilot duties for the rest of the round trip, thanks to the private pilot’s license he’d earned at 16.

While stationed overseas, Hinkle’s first stop in Vienna was to board the Riesenrad, a 212-foot-tall Ferris wheel. It was a precursor to a ride he’d take a few years later, on a Ferris wheel much closer to home, with his good friend James Dean.

Not bad for a kid from Brownfield who didn’t officially exist on paper until his 20s.

Web Extra: “He stole the movie,” Hinkle says of James Dean in Giant. “As good as those other people were, he stands out, doesn’t he?”

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

The country doctor who attended Hinkle’s birth on an unelectrified Terry County ranch in 1930 misrecorded his first name as “Bobbie.” It didn’t get corrected until some 22 years later, when Hinkle went to the courthouse with his aunt and uncle in tow to vouch for his identity. Today, the nonagenarian takes that misnomer in stride, along with the doctor’s weekslong delay in recording his birth on the county rolls. “That old doctor,” he says, not unkindly. “At least he got me here.”

Hinkle’s family followed the crops around for work for a time after his birth. “We were poor,” he says. “They were poor people.” After the military and before setting out for Hollywood, Hinkle worked as a weekend rodeo cowboy and in construction, among other jobs. His 12-hour shifts in a West Texas oil field in 1950 and 1951 earned him $1.76 an hour and, years later, a foothold in a conversation with Howard Hughes, the manufacturing scion and film producer.

Web Extra: From left, Dennis Hopper, Monte Hale, Fran Bennett and Hinkle on the set of Giant.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

An uncredited role in a 1956 film, The First Traveling Saleslady, led to a chance meeting of the two Texas transplants in Hollywood. After being instructed by the director to all but pretend not to even see Hughes as he visited the set, Hinkle was wrangled into meeting him anyway when the film’s star, Ginger Rogers, walked him over. The inventor didn’t offer to shake hands, Hinkle says, but the two quickly found common ground: Much to the magnate’s approval, the drill bits the supporting player had used in his oil field days were manufactured by Hughes Tool Company.

During Giant’s 1955 production, Hinkle, James Dean and Elizabeth Taylor, along with a handful of other cast and crew members, repaired to Dallas over the Fourth of July weekend, all because the famously violet-eyed star couldn’t resist the siren song of Neiman Marcus. Hinkle called the luxury retailer and dropped a few names. Stanley Marcus, the store’s owner, not only agreed to allow the group entry to the store on a Sunday, when it would typically be closed, but also sent a plane to Marfa to whisk the group to Love Field.

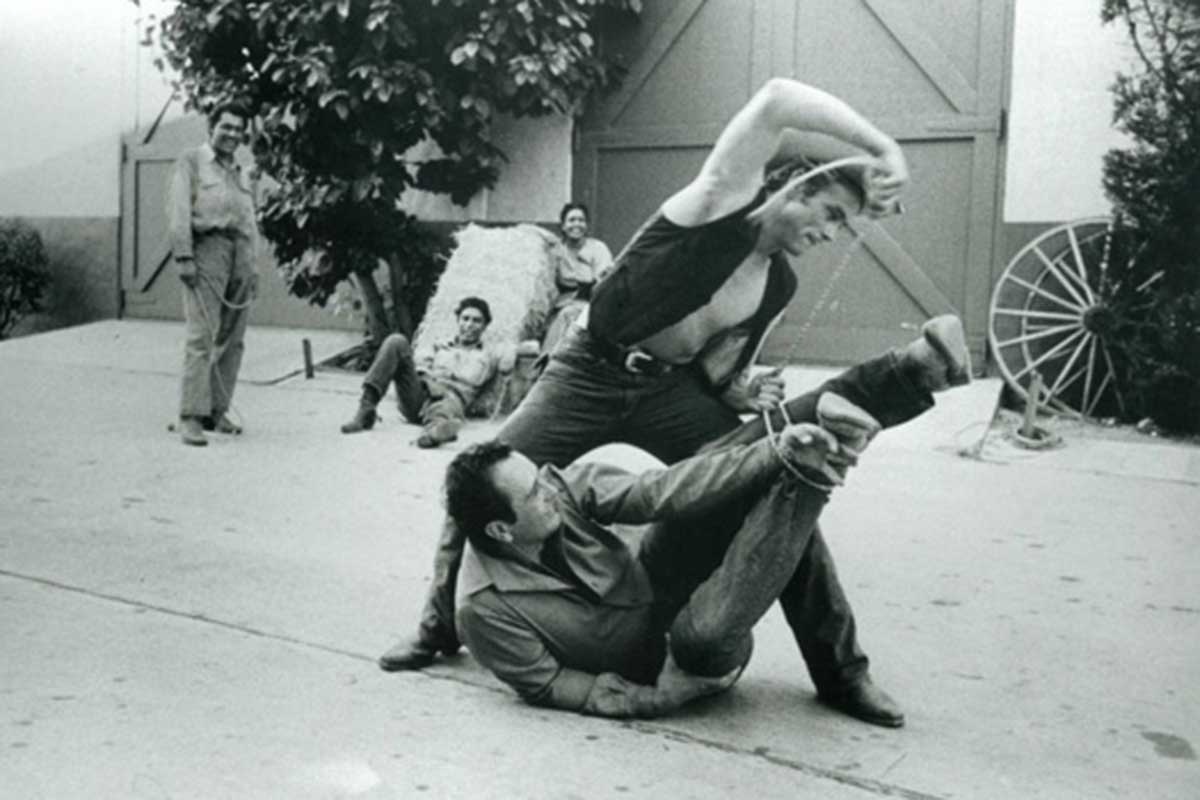

Web Extra: Hinkle and Dean work on lassoing.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

After being feted by Dallas society in Stanley and Billie Marcus’ Highland Park mansion, Hinkle, Taylor and Dean embarked on their shopping excursion, followed by an outing to an offseason Fair Park, home to the state fair, where they rode a rickety wooden roller coaster, sampled carnival fare, played midway games and boarded the soaring Texas Star.

The lighthearted weekend contrasted with Dean’s intense focus on getting the part of Jett Rink, the anti-hero of Giant, just right.

“He told me, the day I met him, ‘I want you to help me be a Texan 24 hours a day,’ ” Hinkle says. During filming, the pair grew close as the dialogue coach modeled Texan sensibilities for Dean. They shared meals, pulled pranks and hunted rabbits together. “He was like a brother,” Hinkle says, “just like I was raised with him there in Brownfield.”

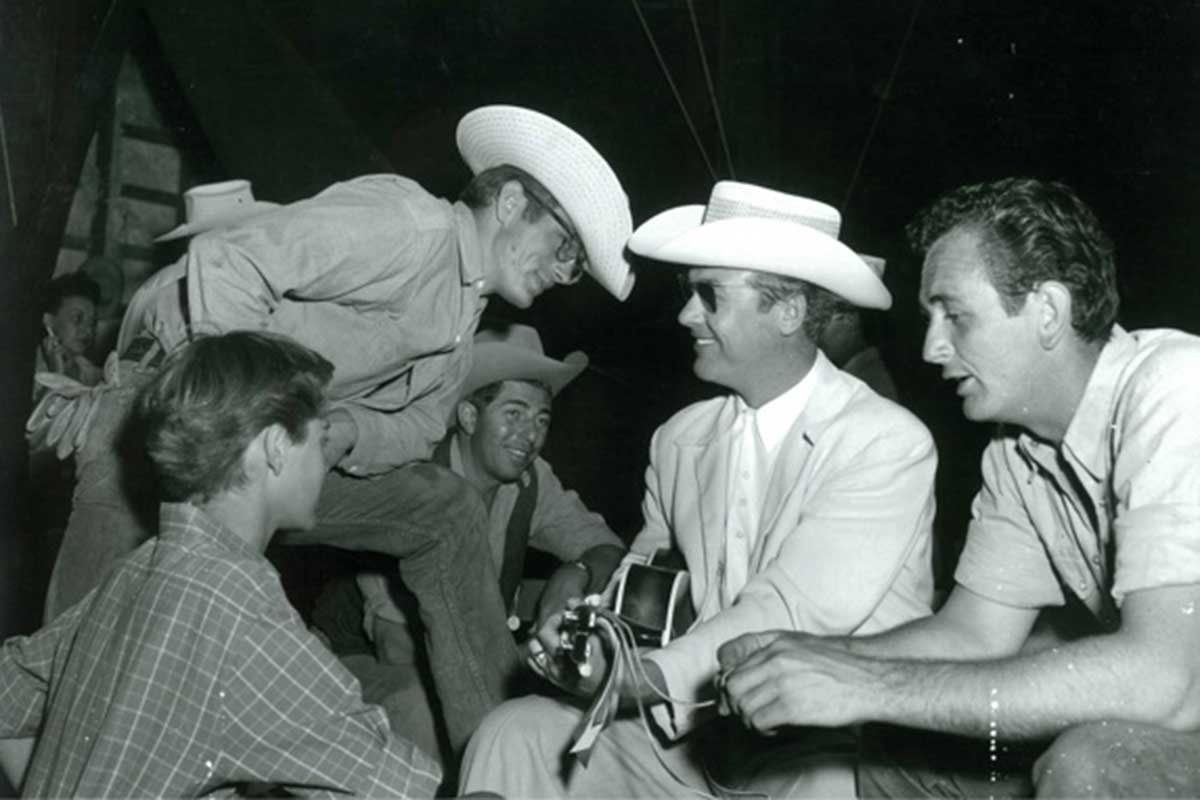

Web Extra: Monte Hale plays guitar for an audience that includes Dean and Hinkle after hours during the filming of Giant.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

Hinkle says Dean wasn’t a big star then, having only one film credit at the time. But his commitment to his craft and his precision in shaping a character in the likeness of his mentor precipitated a friendship.

“He was so dedicated,” says Hinkle, a Pedernales Electric Cooperative member. “He wanted to be with me all the time. Because he wanted to be a Texan. I mean, he watched everything I did and everything I said, watched every person that I met, how I met ’em and things like that, and he just studied it.”

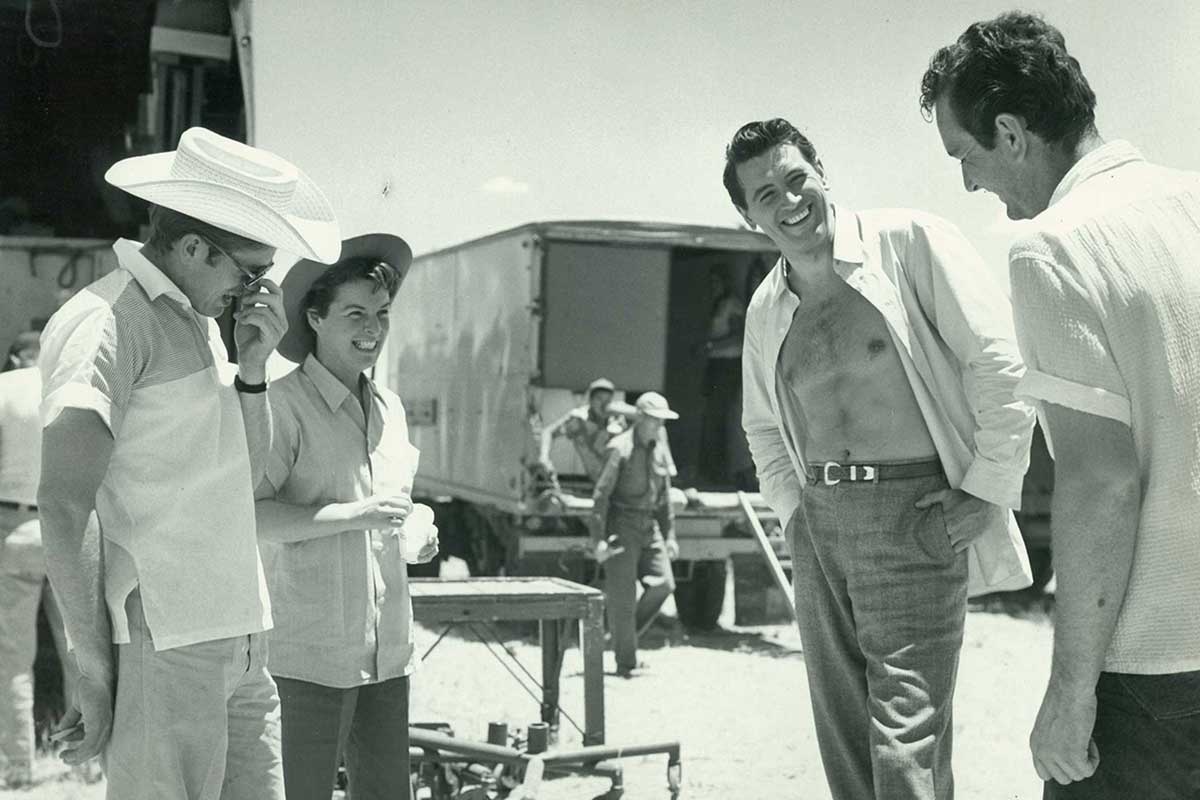

Web Extra: Hinkle with Rock Hudson, left.

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

That osmosis translated to the screen. Dean received a posthumous Oscar nomination for the role, which came as no surprise to his grieving friend.

“He could have played Giant a different way, you know,” Hinkle says. “He wanted to play him just as an old down and out cowboy, didn’t have anything and didn’t figure he’d ever have anything, except a dream.”

After filming of Giant ended, Dean gave a replica Oscar to Hinkle, inscribed with his name, to thank him for creating the character.

Web Extra: From left, Dean, Mercedes McCambridge, Hudson and Hinkle share a light moment. “I was a cowboy stuntman before Giant,” Hinkle says. “It changed everything. Hobnobbing with people like Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, that knew me by name and asked me questions and actually took my suggestions. That changed my whole way of thinking: Well, hell, you know, just ‘cause I was born out there in West Texas and fell off of a damn turnip truck, I didn’t do it last night. I can do anything I want to do.”

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

Back at the Masonic Lodge, the afternoon unspools. Just before he tells me about recruiting Buddy Holly to headline a car-selling telethon starring Western character actor Chill Wills, strains of El Paso fill the room. It’s Hinkle’s iPhone ring tone. His eyes crinkle. “That’s Marty Robbins,” he says. “I managed him for 14 years.”

Web Extra: Dean and Hinkle. “He wanted to be just like me,” Hinkle says. “[Giant co-star] Earl Holliman, the last time I saw him, said, ‘Boy, when I watch that picture, I sure see a lot of you in that Jimmy Dean.’ ”

Courtesy Robert Hinkle

Looking back on his half-century career, spanning roles from cowboy stuntman to mentor to manager and many points in between, I ask if there’s anything he’d change.

“No,” he says. “I’d just love to do it again. I’ve had a lot of rough times and things—boy, I’d take them right along with the good ones, if I could just do it one more time.”

Jessica Ridge is a TEC communications specialist.