The billboard rises above State Highway 71 outside of Ellinger, reminding drivers they can stop at Weikel’s Bakery, some 10 minutes farther west in La Grange, to buy kolache. The billboard is little different from thousands of others advertising roadside stops in Texas, save for one thing. The Weikel’s billboard almost towers over Hruska’s Store & Bakery on Highway 71. Hruska’s sells kolache, too, that are equally as famous as Weikel’s.

Think barbecue is taken seriously in Texas? Wait until you hear about kolache.

“Kolache is a symbol,” says Denise Mazel, a Czech native and chef who owns the Little Gretel restaurant in Boerne. “Kolache is a small pastry, but to every Czech, it represents family. So everyone is going to say their kolache is the best and their recipe is the best.”

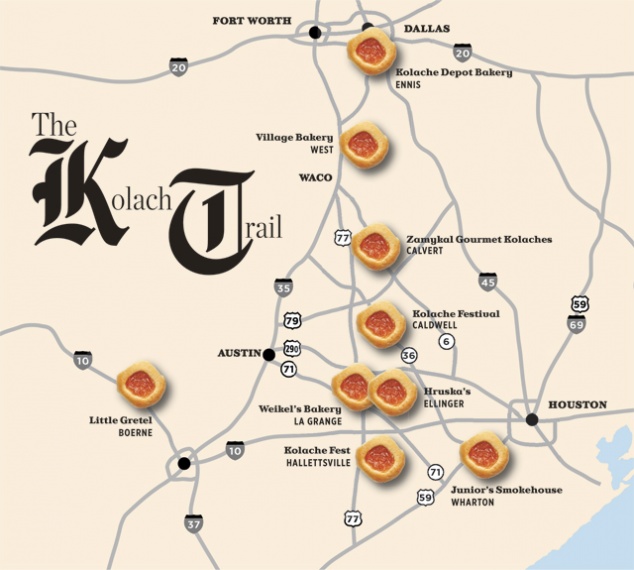

Kolache, plural for the Czech word kolach, are one part sweet roll and one part tradition, and have been a Central Texas staple since Czech-speaking immigrants brought them with them in the 19th century. They might not be as famous statewide as barbecue or chili, but partisans are just as loyal, just as opinionated and just as ferocious in their sympathies. Want to start an argument in Hallettsville, home to the annual Kolache Fest each fall? Say something nice about kolache from West or Ellinger or La Grange or Wharton.

Call it a kolache state of mind.

“You can travel across the United States, and at every exit you’ll see McDonald’s and Jack in the Box and Taco Bell,” says Imran Meer, who owns the Kolache Depot in Ennis, about 40 minutes south of Dallas. “Even in Ennis, a small town, we have five Subways. But you don’t find kolache on every corner. That’s what makes it unique, and that it’s unique is why it’s still popular, even after all these years.”

A Long Tradition

Anyone who has driven Interstate 35 more than once knows about West, 15 minutes north of Waco and home to three kolache bakeries—impressive for a town of just 2,800 people. But kolache are about more than geography; there are kolache bakeries as far east as Corpus Christi and as far west as Lubbock, and even in the four big cities—anywhere, apparently, where someone has a recipe, often handed down from the old country, and the wherewithal to use it. Still, if there is a focal point for Texas kolache, based on the concentration of bakeries and Czech communities, it’s probably the area between Austin and Houston that includes Hallettsville, Ellinger, La Grange and Wharton. Yet residents around Caldwell, near College Station and home to a kolach festival of its own, almost certainly will take issue with that in the finest kolache tradition.

“We eat a lot of kolache here,” says Sharee Rainosek of the Hallettsville Chamber of Commerce, who oversees the 19-year-old kolach festival and the chamber’s kolache sales (about 500 dozen a year), kolache queen pageant, kolache-eating contest and, for the last two years, the baking of a 6-foot-long kolach. “This is an area with a long history of Czech and German immigrants, and that means we have a long history of kolache.”

The pastry can trace its Texas roots to Czechs who settled in Central Texas before and after the Civil War. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were 250 Czech communities in the state, according to the “Texas Almanac.” Traditionally, kolache were made at home, with bakery-made pastries unheard of (still true in the Czech Republic). They were made with a sweet yeast dough, hollowed in the center, filled with fruit and eaten as an afternoon snack. Fillings were simple—apricots, poppy seeds, prunes and cherries, all available locally in Eastern Europe. Kolache were similar to other Eastern European pastries such as the Polish piernik and a Ukrainian sweet where filling was placed inside rolled dough.

A century later, much has changed, except for the basic recipe. Finding homemade kolache is becoming more and more difficult, says Rainosek, thanks to the usual 21st century reasons—more women in the workplace, an emphasis on convenience foods and generations further removed from the idea that kolache should be homemade.

Fillings have become almost exotic—pecan pie and chocolate coconut cream among the 30 varieties at Zamykal Gourmet Kolaches in Calvert, for example. The modern bakery, whether the traditional Village Bakery in West, with its lace decor and its claim to be the oldest Czech bakery in the state, or the truck stop-like Hruska’s and Weikel’s, is now where most people, Czech heritage or not, get their kolache.

Always Evolving

This is part of what Jamie Allnutt, the marketing manager at the Village Bakery, calls the kolach’s resurgence in popularity. It’s not so much that the pastry ever went out of favor; rather, she says, “people are going back to their roots, and they want to experience other people’s ethnic roots. It makes them happy when they do that, and they can do that with kolache.”

She divides the postmodern kolache world into three parts:

• Gourmet, where bakeries focus on nontraditional fillings and attempt to update the pastry for the 21st century. Kolache, in fact, have been embraced by the artisan food movement, and trendy takes on kolache are popular in Austin and Houston.

• Bigger is better, where bakeries focus on size.

• Tried and true, where bakers make traditional kolache as they were made in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Which brings up the question that everyone has an answer for, and which is different for everyone who has an answer: What are the best kolache?

The question can’t be answered because, as Jude’ Routh, who owns Zamykal with twin sister Jody Powers, notes, “The thing about kolach recipes is that every family recipe is different, like every family has a different recipe for meatloaf.”

Each region—no, each bakery—has its partisans, and none of the others measure up, in the same way that two people will argue about whether mesquite and direct heat barbecue is better than pecan and indirect heat barbecue as long as either can take a breath. One bakery’s dough is too soft or too yeasty while another’s fillings are too sweet or too fruity. Or it may come down to the kolach not being round enough, because shape matters. Besides, is that other recipe really that authentic? And none of this takes into account the sausage-filled kolach, which isn’t really a kolach at all and often brings on another round of argument (see sidebar below).

And don’t even bring up kolache sold at chain doughnut shops.

The irony is that many of the kolache in Texas have one important thing in common—most of the recipes are authentic, handed down from generation to generation. Routh talks about the family recipe that took three years to perfect. Teresa Jones, who owns Hruska’s, talks about her bakery’s passion for what she calls its original style of kolache. Kalan Besetsny, whose family owns five Besetsny’s Kountry Bakeries in Central Texas, credits his grandmother’s recipe for the business’ success. James Dornak, who bakes kolache at Junior’s Smokehouse in Wharton, uses a recipe from his family, Czech on both sides.

The other irony? Many bakeries, even those that offer exotic fillings, report that their best-selling kolache are the most traditional—apricot, poppy seed and cream cheese.

Regardless of style or niche, everyone sells lots and lots of kolache. Some sell so many that, in the finest competitive tradition, they don’t want to talk about how many. Zamykal, though, which is located in a town with one stoplight on the way to towns not much bigger, will sell as many as 300 a day. At its Hallettsville location, Besetsny’s will sell some 8,000 a week, and Junior’s Smokehouse sells a couple thousand each week.

This, ultimately, is why kolache have endured and evolved over the past 160 years.

“It’s about our German and Czech heritage,” says Besetsny. “It’s still out there, and here in the country; it’s still in the blood. People remember their grandmother making kolache, and they want to relive that. They want to remember what that was like.”

Which is a fine thing for any pastry to be ableto do—even if no one agrees what it’s supposed to taste like.

——————–

Jeff Siegel is a Dallas writer.