Cow women “simply took their freedom, much to the relief of their men, who always needed help … They learned to ride as equals with men. Because firearms were a necessary part of everyday life, they used them when they had to. They dealt with hostile Indians and cutthroat rustlers. On the trails, they endured and often enjoyed the rustic conditions,” historian James M. Smallwood writes in Texas Women on the Cattle Trails edited by Sara Massey (Texas A&M University Press, 2006).

All 16 women profiled in the book are compelling, but I find Sara Massey’s account of Lizzie Johnson Williams (1840-1924) especially intriguing because Lizzie’s outlook was so modern and idiosyncratic. It was the polar opposite of my more traditional grandmother. Born over a half century later than Lizzie, in 1898, a mere three years shy of the Victorian cut-off, my grandmother far more fit that era’s definition of womanhood. She was raised in a two-room house on her father’s small Texas Panhandle cotton farm. She received a third-grade education.

Being born into a family of educators, Lizzie spent her childhood learning about arithmetic, spelling, grammar and music. By the time she was 16, she was teaching in her father’s Hill Country school system known as the Johnson Institute. In her mid-20s, Lizzie started making extra income by keeping the books for local cattlemen. She quickly learned the cattle trade, and her bookkeeping business became very lucrative. Still, she found herself bored at times, so she began publishing pulp fiction using a nom de plume and made enough money to start investing in cattle and buy her own home in Austin. At 32, Lizzie was a single, professional woman living on her own and making good money.

By contrast, my grandmother married my grandfather when she was 16. They remained on her family’s farm and cared for her parents until their deaths. I never once heard my grandmother mention being bored. When she wasn’t cooking and cleaning she was quilting and sewing. The closest she ever came to understanding the cattle business was performing her daily task on an overturned bucket at the south end of a milk cow.

Lizzie became a cattle broker after the Civil War and eventually invested in a Chicago cattle company. Originally worth about $2,500, the stock paid 100 percent for three years straight, and Lizzie sold it for $20,000. She invested in more cattle and land, lots of it. This was early in the cattle boom, and she was able to dispatch her cowhands to round up wild cattle and brand them. She was sending cattle up the trail to market by 1879.

In Lizzie’s day, young women were considered spinsters if they weren’t married by their early 20s. But Lizzie, who turned down several fervent suitors, wasn’t ready for marriage until the age of 39 when she fell in love with Hezekiah George Williams, a fellow cattleman and retired preacher with seven children. Lizzie was smitten, but romance didn’t alter her shrewd business sense. She insisted that Hezekiah sign a contract saying that her property, along with all future financial gains she might make, belonged to her. The idea of such a “pre-nup” would’ve been foreign to my grandmother.

In the mid-1880s, Lizzie and Hezekiah made at least three trips up the Chisholm Trail taking their separate herds. A ranch foreman recounted that both Lizzie and Hezekiah instructed him to appropriate and brand the other’s unbranded calves. Lizzie went to cattle sales with Hezekiah, but they bought separately. Lizzie turned out to be the better judge of cattle and the stronger moneymaker.

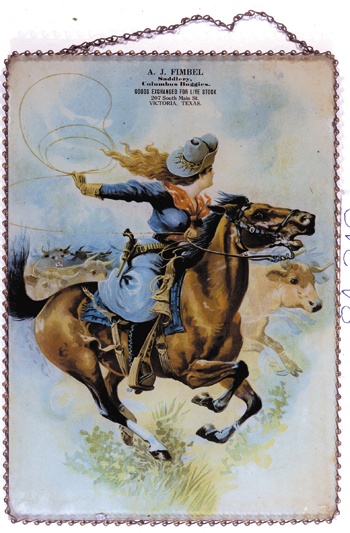

When she had the opportunity, Lizzie wore fine silks and velvets purchased in New York and Kansas City, and on one trip she bought $10,000 worth of jewelry. But on the trail, she donned calicos and cottons, a bonnet and a gray shawl and rode in a buggy.

At the end of the century, Lizzie and her husband traveled extensively, staying in fancy hotels and shopping for elegant clothes. When Cuba became a market for Texas cattle, Lizzie and Hezekiah moved there and stayed for three years. At one point, Lizzie lost a $40,000 shipment of cattle, but it obviously didn’t break the bank.

Less than a year later, Hezekiah was kidnapped and held for $50,000 ransom, which Lizzie promptly paid. After that, she made him sign all his property over to her. They returned to Galveston on Christmas Eve in 1905.

Despite their friendly rivalry, Lizzie loved her husband. When he died in 1914, Lizzie paid $600 for a fine casket. “I loved this old buzzard this much,” she wrote across the undertaker’s bill.

By then she owned property in Llano and Hays counties and buildings in Austin. She owned a 4,300-acre ranch in Trinity County, a 10,000-acre ranch in Culberson County, and acreage in East Texas near Conroe. One thing she didn’t have was a close family. In her later years, she became reclusive and lived out the rest of her life in her Brueggerhoff Building in downtown Austin. She no longer lived in grand fashion but became a miser, bargaining down the price of her morning orange juice. She died a decade after Hezekiah without leaving a will. Her distant family was left to sort out her estate, worth over a quarter of a million dollars.

My grandmother never left her Texas Panhandle farm. Every morning for 86 years, she woke up and looked out the back door at the same horizon. She rode in a buggy a whopping 20 miles away on her honeymoon. It was the farthest she had ever been from home, and the farthest she would go for years to come. She never learned to drive a car. She never traveled on trains or airplanes. To my knowledge, she never owned a diamond.

She outlived my grandfather by two decades and died in 1984, still light-years behind Lizzie in independence, self-confidence and wealth. But she did have a family and she left a will, and because of it I am able occasionally to stand at her back door and take in the same Panhandle horizon she saw every single day of her life.