Editor’s Note This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org.

Mike Harrell grew up like many in rural Texas in the 1960s, with a passion for sports and the outdoors but most of all hunting and the solace it provided. Particularly the solace.

As a boy, he’d ramble through the Central Texas flatlands north of Austin, stalking whatever was in season. Alone time. Just him, the quarry and his thoughts.

After Harrell graduated in 1974 from Florence High School, where he was a standout in track, baseball and football, he needed to find a vocation to match his avocation. His father, Milton, owned an electric shop, so he went to work for him.

Harrell didn’t mind the work. “What I didn’t like was dealing with people, especially service calls,” he recalls five decades later. “It got to the point I told him I wasn’t going on any more service calls.”

So like any good electrician, Milton completed the circuit by removing the barrier. Harrell would only work on wiring new houses and rewiring uninhabited ones.

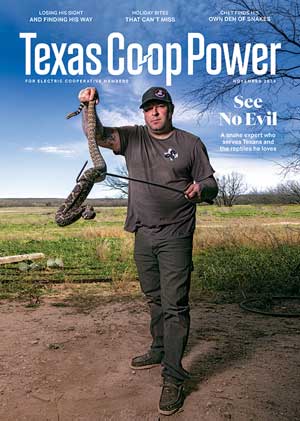

The hardest job was yet to come. By 28, Mike Harrell would be completely blind. Now he had to rewire himself.

After losing his sight, Harrell found his way around a dominoes table.

Eric W. Pohl

Sometimes people meet the sturdy 68-year-old retiree—whether it’s at a Texas 42 dominoes tournament or representing Florence as a volunteer city council member or anyplace outdoors, really—and before long, they’ll drop words like “amazing” and “impressive.” But Harrell isn’t impressed.

“I’ve been told that before,” he says. “But I’m just like everybody else.”

Except Harrell lost the sight in his left eye in a hunting accident when he was 16. Walking in the darkness, a branch whacked his face. “It hurt,” he says, “but it really didn’t bother me a lot.”

Monday came and the pain was worse, and his sight was blurry. It kept worsening, and doctors couldn’t stop it. Pretty soon the eye stopped seeing, the result of inflammation of the optic nerve.

Harrell adapted. He could still excel as a one-eyed tight end and defensive end in football, and he stayed formidable in track, running the hurdles. He did it by studying his motions between steps, memorizing every nuance, until he ran them by rote.

He began working as a roughneck locally and then on an offshore rig reachable only by helicopter. He settled down, got married and started a family.

He’s become an expert at reading the pips—indentations—on his pieces by touch.

Eric W. Pohl

One day, while welding a broken trailer latch, he thought he’d gotten something in his right eye. He looked at it in the rearview mirror, and it was bloodshot.

An ophthalmologist prescribed corticosteroids to fight the inflammation. “All I could see is if you look at the sun and it looks like a damn light bulb,” Harrell says.

So he had his first operation. “I could tell what color hair people had or what color their clothes were,” he says. “I got excited.”

Neither the excitement nor rudimentary vision lasted. His retina wouldn’t attach correctly, not with a second or third operation. Then came the dreaded words: “There’s nothing else we can do.”

“I was devastated,” Harrell says. “I didn’t depend on nobody for nothing. I did everything myself. Now I can’t even drive. Can’t see my family. I can’t see my kids.

“It was pretty rough.”

Friends wanted him to go to the Criss Cole Rehabilitation Center, a state facility in Austin that trains people with limited vision to have productive lives, but the only facility he was interested in served equal parts alcohol and self-pity.

For a year and a half, he drank and couldn’t find work.

Harrell and partner Keith Kyle with their second-place trophy won at the 2023 Texas State Championship Domino Tournament. “I think I’m a dagburn good player,” Harrell says.

Eric W. Pohl

One night he took out a shotgun and sat on the bed, when he heard the voice of his toddler son.

“I didn’t know my son was in the bed,” Harrell recalls solemnly. “He grabbed me around the neck and said, ‘Dad, don’t do it.’ ”

Harrell pauses in reflection.

“I didn’t know whether I would have pulled the trigger if he hadn’t been there,” says Harrell, who’s estranged from his first family. “I never told anybody about that and don’t know if he’s old enough to remember or not. I don’t know.”

A bit before Harrell turned 30, he gave himself a present: self-awareness.

“That’s the time where I said, ‘You know, I’m gonna have to do something about this,’ ’’ he recalls. “I remembered sitting with my grandma, and she was telling me, ‘I know it’s a terrible thing you lost. But you know, if you just look around, there’s always somebody in worse condition than you are, and most of the time, you don’t have to look very far.’ ”

He found it at the CCRC. Harrell couldn’t master Braille because his fingertips were too calloused from oil field work, but he learned woodworking and other manual skills, though he could never figure out why he was required to wear safety goggles.

Harrell, a Florence City Council member, memorizes his pieces as he feels the pips.

Eric W. Pohl

He patched up his relationship with his higher power, discovering hidden blessings in his experience. Ultimately, he also found a career. He decided on transmission building and repair, tactile but challenging, applying the same memory skills he learned while running hurdles in high school.

Gradually he learned to make money from it, started his own shop, got remarried, started a second family, got divorced again and finally retired five years ago. At 4:30 a.m. every weekday he hitches a ride to the local gym to work out.

“Some people with disabilities feel stuck,” says Jessica Kovarna, one of his two daughters from his second marriage. “He’s the opposite. It’s like he doesn’t have one, just a minor inconvenience.”

Former Mayor Mary Condon, who remembers meeting Harrell when she first moved to Florence in 1978, says he has evolved into a man steeped in faith and self-acceptance.

“Because he’s blind, people tend to tiptoe around him,” she says. “Mike just replies by making fun of himself.”

Harrell enjoys a game with friends in Florence.

Eric W. Pohl

One day at church, a well-intentioned guy offered to help him find his way. “No, I don’t need help,” Harrell said brusquely.

The pastor overhead Harrell and cornered him. “If you won’t let that person help you,” the pastor said, “you are taking a blessing from someone.”

Harrell accepted that help.

When Harrell was a child, he watched his mom and her siblings play Texas 42. He studied the game, joined in when he was in high school and kept playing until he lost his sight.

At CCRC, he discovered a set of dominoes. Excited at something familiar in his hands, he resumed playing and even bought a set with the dots raised instead of indented.

Decades later, his dominoes schedule is full. A typical week has Sunday games at his aunt’s house, Monday at Salado Creek Saloon, Tuesday in Liberty Hill, Wednesday at his church, Friday warmup for a Saturday tournament and tournament play on Saturday at spots around Texas.

“I like competition,” Harrell says. “One reason I chose automatic transmissions to rebuild was because of the challenge doing that and being blind. That’s the same reason I play dominoes. The competition and the challenge.”

Harrell gets a couple of accommodations for 42. He’s allowed to feel the dominoes to identify the numbers they carry. And he can also ask what tiles have been played. “He keeps what’s been played in his head,” frequent partner Keith Kyle marvels. “His memory is amazing.”

In 2023, he and Kyle took second place at the state 42 dominoes tournament in Hallettsville, winning $115, matching trophies and some admiration. They expect to try again for the state title next spring.

You might not think a city of 1,170 people requires a city council meeting lasting almost three hours, but the folks entrusted to shepherd the interests of Florence are nothing if not thorough.

During the July meeting, Harrell sits in the overstuffed chair at the dais and mutters a whole lot of “seconds” and “yesses” and not much else.

“And you thought I talked a lot,” he says to the only public spectator who stayed for the duration.

Condon finishes up a conversation with the current mayor and finds Harrell.

“You ready to go?” she asks.

Harrell puts his hand on her shoulder, and they set out for her pickup truck. “I was ready 2½ hours ago,” he cracks.

Just people. People helping people.