Nearly everyone has their passion. Some people love to garden, hike or travel. Others play video games, dance or volunteer.

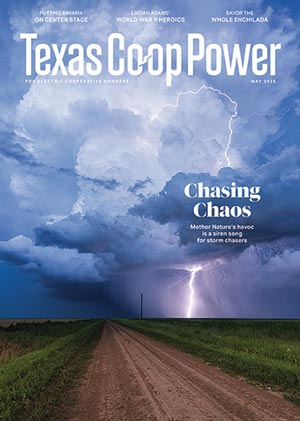

Chelsea Burnett chases storms. Her unusual passion surfaced at age 2 in the late 1980s, when, upon hearing thunder, she’d rush to a window and search the skies.

“As I got older, I watched the Weather Channel and local weather updates,” recalls Burnett, who lives in Little Elm, north of Dallas. “I had weather calendars, and I’d cut out newspaper articles about weather in the region. I also had a weather radio alarm clock that played local forecasts.”

Today, Burnett, a member of CoServ, makes a living from weather-related work. So does her husband, Adam Lucio. Their mutual passion led them to become storm chasers—a term for professional and amateur weather watchers who pursue tornadoes, hurricanes and other severe weather.

Why? Some want to see their first tornado. Many crave the adrenaline rush. Others photograph storms for spectacular images, scientific research or news coverage. And these days, social media, mobile devices and even tour groups are making it easier than ever to find and share stunning storms despite extreme risks.

Modern-day chasers follow in the wake of David Hoadley, considered to be the father of storm chasing. In 1956, he photographed the aftermath of a severe thunderstorm in his hometown of Bismarck, North Dakota. His fascination led him to drive after and document storms using his own forecast maps. From 1977 to 1986, he published Storm Track magazine for the growing chaser community.

At 86, Hoadley, who lives in Falls Church, Virginia, still chases.

“It’s a challenge,” he says. “I enjoy intersecting storms and getting pictures. I just do what I like to do.”

Some words of warning: Chasing is dangerous, sometimes deadly. And even despite the best of safety precautions, accidents happen. In June 2013, three veteran chasers were killed by a tornado near Oklahoma City. Other chasers have died in car crashes while on the road.

In 1996, daring risk-takers came to life when Twister tore into theaters nationwide. The disaster film—which inspired a generation of weather scientists—stars Helen Hunt and the late Bill Paxton as storm chasers trying to release data-gathering sensors into a tornado in hopes of improving early warning systems.

The same goal returns in Twisters, the action-packed 2024 sequel that features scientists and chasers going up against tornadoes in the social media era using more sophisticated technology.

A Tornadic Expeditions tour in April 2021 came across a rare weather phenomenon in Lockett: a tornado alongside a rainbow.

Courtesy Erik Burns

A storm cell produces lightning beyond a church in Gainesville.

Courtesy Chelsea Burnett

Tim Marshall of Flower Mound, in the Metroplex, Hoadley’s protégé, started storm chasing in 1978. In those days, he’d stop at pay phones to call the National Weather Service for radar updates. Then he and his partner would take off for a location where a storm might intensify. Or not.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, the odds of catching a tornado were 1 in 20 times when you went out,” says Marshall, who has seen hundreds of twisters. “Now it’s 1 in 8 or 10. It’s still more miss than anything, but the odds are better because of our technology.”

Marshall and Hoadley were among the six inaugural inductees to the National Storm Chaser Hall of Fame in February. Professionally, Marshall, a CoServ member, has worked since 1983 as a meteorologist and forensics engineer. As part of his job, he assesses damaged buildings after catastrophic weather events.

A Tornadic Expeditions tour pursued this supercell for 125 miles across West Texas, from Spur to Tuscola.

Courtesy Erik Burns

Tim Marshall and Carrie Cunningham met in 2010 chasing storms for the Vortex2 research project.

Courtesy Carrie Cunningham

“Before a storm, power crews prestage their trucks,” he says. “So the first people I see coming into a disaster area are the power crews. It’s amazing how many of them get ready and are there once law enforcement clears the roads.”

Most chasers carry first-aid supplies in case they’re the first on the scene of a disaster.

Carrie Cunningham of Boerne, near San Antonio, met Marshall in 2010 when she volunteered with Vortex2, which was the largest tornado research project of its kind. As a driver, she was among a team of more than 100 scientists and crew members, with 40 support vehicles and 10 mobile radars, who raced after supercell thunderstorms for six weeks across seven Midwestern states.

On June 10, 2010, she witnessed her first tornado with Marshall near Denver. Every season since, she and her husband, Doug, have chased with Marshall. When forecasts and weather models predict risky conditions, the couple pack up and head north.

“We call them ‘chase-cations,’ ” says Carrie Cunningham, a member of Bandera Electric Cooperative. “It’s not always about seeing a tornado. I just love to drive, visit the small towns, eat in cafés and meet new people. For me, it’s spiritual being with the storms and nature.”

Then there’s the tradition among the community of eating a steak after a sighting.

“Some of our family think we’re crazy,” she says. “A lot of friends are fascinated, and some say they’d love to go with us.”

For more casual storm adventure seekers, chasing tours can be booked through many companies in Texas and beyond. That is, if they’re not booked up, thanks to renewed interest inspired by Twisters.

For example, Tornadic Expeditions completely sold out for 2025 tours by the end of 2024, and 2026 will fill soon. Erik Burns, a Grayson-Collin Electric Cooperative member who lives in Whitesboro, near the Oklahoma border, launched the niche business in 2015.

“On a seven-day tour, we cover about 2,500 miles,” says Burns, who met his Australian wife, Emma, on one of his 2019 excursions. “Our tours are laid-back and personable. We only put four guests in a van, so everyone’s got a window seat.”

The U.S. experiences more tornadoes than any other country—about 1,150 per year, which is about five times what Europe will see in a year. And 2024 was the second-worst tornado season on record in the U.S., with more than 1,735 confirmed twisters, including 169 in Texas—more than any other state. On average in the U.S., 73 people die in tornadoes per year.

Burns and his chaser guides conduct five- to 10-day trips from April into July across Tornado Alley, a twister-prone area that roughly spans north from Texas up to Nebraska and South Dakota. Tours may also venture into neighboring states, depending on weather. Guests travel in vans equipped with Wi-Fi, cameras and laptops loaded with radar and satellite-tracking software.

A Tornadic Expeditions tour watched this twister in Hawley stay on the ground for 24 minutes.

Courtesy Erik Burns

Texas A&M University students studying atmospheric sciences launch balloons for National Weather Service research.

Courtesy Chris Nowotarski

Since 2018, Ray Myers of Plano has been on three Tornadic Expedition tours. He’s also accompanied Burns on numerous solo trips. On April 23, 2021, the two witnessed five tornadoes near Lockett, west of Wichita Falls, including twin tornadoes and one that spiraled next to a rainbow. What was his reaction to seeing his first?

“I said, ‘Oh, look at that! Oh, look at that—look at that—look at that!’ ” recalls Myers. “There are just no words. You are witnessing one of the most powerful things in nature. Some people go speechless. Some cry.”

Storm chasing has even joined the collegiate world. Since 2020, the department of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University has offered a spring course called convective storms field studies. Students are trained on how to storm chase, forecast tornadoes and conduct field research.

“Then for two weeks in May, we go out storm chasing,” says Chris Nowotarski, an associate professor. “The students take turns forecasting and navigating where they think there will be storms in the Great Plains. They also launch weather balloons and send the data to the National Weather Service.”

After graduation, “our meteorology majors go on to become forecasters for the National Weather Service, private forecasting companies or aviation companies that need weather forecasts,” Nowotarski says. “Some go into grad school to do research related to severe weather or other weather. Some go into television.”

A Tornadic Expeditions tour poses with a tornado in 2022 in Crowell.

Courtesy Erik Burns

Schooled or not, storm chasers provide information that advances scientific understanding of weather.

“Many amateur storm chasers are more focused on collecting photography and videos of tornadoes, which may be less useful in improving our understanding and prediction,” Nowotarski says. “But these chasers report tornadoes to the National Weather Service. These reports are critical to developing an accurate record and climatology of tornadoes that can be used for future studies.”

Although she has no meteorology degree, Chelsea Burnett has years of hands-on training and experience. She’s a tour guide for Tornadic Expeditions and a public speaker with Storm Science, which conducts educational weather programs. She’s also a member of Girls Who Chase, an online group that encourages and connects women who want to storm chase, and is a chaser and speaker with Texas Storm Chasers.

In her chasing career, Burnett has gone after 70 twisters (and three hurricanes). But—like all storm chasers—she’ll never forget her first. On the night of December 26, 2015, she was standing outside a gas station near Red Oak, south of Dallas, when power flashes and lightning illuminated the sky—and a tornado.

“I couldn’t believe I was seeing one,” she recalls. “It was the most incredible moment of my life! You’re eye to eye with one of Mother Nature’s most raw processes. To see a tornado come together truly is a spiritual moment.”