It’s a scene straight out of a campy old Western.

After a long day of driving cattle—from 5 a.m. until dark—that ends with pushing the herd to a cattle trap by an old Army air base, full-time cowboy Stephen Weathers rendezvous with fellow cowboys finally relieved of their saddles.

“Then we’d sit around the campfire, cooking cans of pork and beans and have a great time joking around,” he says. “When we’d finally get to sleep in the bunkhouse, anyone snoring would get a cowboy boot thrown at him.”

Except this isn’t a dusty trail to Abilene, Kansas, but a Gulf beach in Matagorda County. And instead of a marathon drive, it’s more of a bovine biathlon.

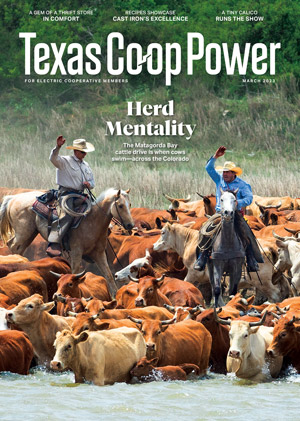

The biannual Matagorda Bay cattle drive is one of the most historic and unique drives in the U.S. For more than 100 years, the Huebner Bros. Cattle Co. has been moving its herd back and forth between winter grazing pastures on the 30-mile-long Matagorda Peninsula and the summer pastures on the family’s ranch south of Bay City. The operation involves swimming the cattle across the 15-foot-deep Colorado River close to where it empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

Huebner Bros. Cattle Co. cowhands drive their cattle off Matagorda Peninsula and across the Colorado River for summer grazing near Bay City.

Erich Schlegel

Logan Meyer, 14, awaits the cattle as they reach Matagorda Bay Nature Park.

Erich Schlegel

Keith Meyer, Huebner Bros. ranch manager, is the fifth generation of cattlemen in his family to organize and run these drives. “Our family has been moving and swimming cattle on and off Matagorda Peninsula consecutively since 1917,” says Meyer, who’s been involved since he was 6 or 7. “I’ve grown up working this cattle drive alongside my father and grandfather.”

The drives move the cattle to the peninsula for the winter months, then move them inland in the spring, just before hurricane season begins and storms threaten their safety. The cowboys time the crossings to occur during periods of slack current, when tidal motion is minimal.

Every November, just before Thanksgiving, about 550 head of cattle are moved in two-story 18-wheeler cattle trucks from the Huebner ranch to a holding pen near the beach. This area is part of the Lower Colorado River Authority’s 1,333-acre Matagorda Bay Nature Park. After passing the coastal fishing town of Matagorda, the cattle are hauled down FM 2031, past homes on stilts along the Colorado River to the west and past 934 acres of protected Matagorda Bay wetlands to the east.

Once the cattle have been delivered to the holding pen and the road is blocked, Meyer and his team of 10–12 drovers lead the herd toward the water. Some of them are local youngsters on horseback who are learning from the more seasoned veterans.

At Matagorda Bay Nature Park, the cattle drive takes a right-hand turn at the miniature golf course to the river’s edge, and the 100-yard swim to the peninsula begins. A small flotilla of cowboys on motorboats ensures the cattle don’t stray, and in about 15 minutes, all are across.

Randy Duncan keeps watch over the spring herd of some 800 cattle.

Erich Schlegel

Lauren Spanihel-Wahlberg helps move the cattle off Matagorda Island.

Erich Schlegel

By the return trip in spring, the herd of 550 grows to about 800 bulls, cows and calves.

“I used to love the cattle drive,” says Weathers, a member of Jackson Electric Cooperative, which serves this corner of Matagorda County. He worked the drive for about 15 years. “We’d get on the peninsula early the first morning and start riding west down the beach. We’d split up our team. Some riders picking up cattle along the beach, some in the dunes covered in salt grass.”

Even though this Beefmaster breed of cattle is known for hardiness in harsh, humid coastal climates, the mosquitoes and biting flies on Matagorda Peninsula can be too much for the herd to handle as the weather warms. The seasonal change challenges the cowboys too.

“The warmer temperatures have brought the rattlesnakes out of hibernation,” Weathers says. “You’ll find rattlesnakes sunning themselves on top of the salt grass, perched about leg high as we ride. The snakes and the biting flies are enough to force some cattle to swim across the river on their own.”

Thus begins the trek back to the Huebner ranch.

“Our ranch pastures have had time to rest over the winter, and the cattle and calves are ready to get going inland,” Meyer says.

The Matagorda drive includes moving the Beefmaster cattle along sidewalks.

Erich Schlegel

Jacie Wahlberg, 7, helps with the roundup.

Erich Schlegel

Jeralyn Novak, communications coordinator for Beefmaster Breeders United, calls the Matagorda Bay cattle drive a modern-day Lonesome Dove. It’s “straight out of the Old West but with a 21st-century spin,” she writes.

Jeff Crosby, executive director of the Colorado River Land Trust, a nonprofit that works to protect land and water in the Colorado River watershed, witnessed a spring cattle swim firsthand. “This is an important part of our historical Texas heritage,” he says.

The cowboys don’t set or share dates for the spring or fall drives, so lucky onlookers have only the weather and tides to go by. After more than a century of trial and error, these efficient workers have the drive down to a science.

“Cattle drives are still done the same way,” Crosby says, “because moving cattle from one location to another was perfected long ago.”