Texas has a surplus of towns identifiable by a singular, defining reputation. Dublin is famous for Dr Pepper. Brenham is renowned for Blue Bell Ice Cream. Gainesville is known for patriotism.

Every April, Gainesville hosts recipients of the Medal of Honor, America’s most prestigious decoration for valor on the battlefield. This community just south of the Red River pays round-trip airfare for any Medal of Honor recipient who wishes to make the four-day visit. City representatives pick them up at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and take them to town in a public safety vehicle motorcade, escorted by hundreds of Patriot Guard motorcyclists. Gainesville hosts honorees in area hotels and allots them cash stipends for general expenses.

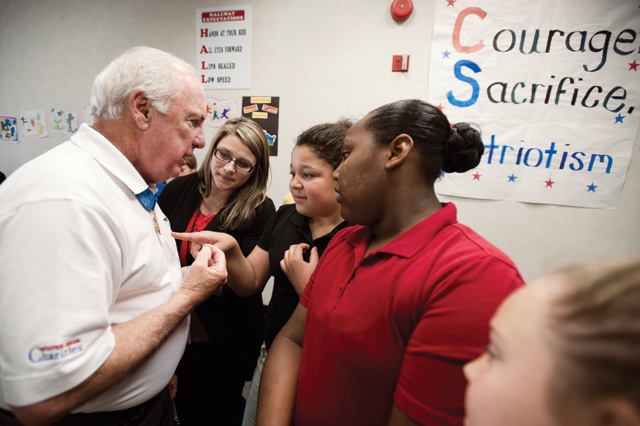

The Medal of Honor Host City Program features a casual dinner, a formal banquet and a citywide parade. In addition, the honorees rub shoulders with Gainesville residents, make appearances at schools and attend other social events to discuss their military service and what the award has meant for them and their families. First-time honorees are also memorialized by tree plantings along Gainesville’s Home Grown Hero Walking Trail.

“It’s a grassroots effort,” says Jenny Richardson, receptionist at the Gainesville Area Chamber of Commerce. “From newborns to folks in their 90s, everybody is involved. When it first started, no one knew how far it would go or how big it would get. Today, anybody who wants to be involved can, whether it’s just standing at the parade waving a flag or giving a ride to one of the events to someone who couldn’t get there on their own.”

Don Pettigrew founded the Medal of Honor Host City Program in 2001 with wife Lynnette. He says the event simply sprang up out of necessity.

Pettigrew, who served with the Marines in Vietnam, had gotten into the habit of attending Iwo Jima reunions in Wichita Falls in the late 1990s and had met all but two of the living Medal of Honor recipients of that World War II battle. When he asked why the two had never made it to the reunions, he was told that neither they nor the event planners could afford the travel expenses.

“I thought someone ought to do something about it,” Pettigrew says. He relayed the disappointing circumstances to then-Gainesville Mayor Kenneth Kaden, who suggested that Pettigrew be that someone.

“The mayor said we could do it in Gainesville,” adds Pettigrew, who has been a member of Cooke County Electric Cooperative for 30 years. “He tasked me with putting together a board and coming up with some guidelines. And that’s how it all started.”

The Medal of Honor was created in 1861 to memorialize American servicemen and women who “conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk” of their lives comport themselves “above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States.” Over those 153 years, American presidents—in the name of Congress—have awarded 3,463 Medals of Honor to the nation’s most courageous soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coast Guard personnel, including 76 Texans. When Gainesville’s Medal of Honor program began in 2001, there were 150 living recipients. Today there are only 76. Forty recipients have participated in Gainesville’s program.

In July 2012, travel and map publisher Rand McNally and USA Today named Gainesville the “Most Patriotic Small Town in America” as part of its Best of the Road promotion. It came as no surprise to former Army Capt. Harold “Hal” Fritz, a 2013 Gainesville honoree and president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, based in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

“The whole essence of Gainesville’s Medal of Honor program is to show that the community and the citizens appreciate what honorees have done to preserve our freedoms,” says Fritz, a 1971 Medal of Honor recipient who lives in Peoria, Illinois. “The people of Gainesville have no hidden agenda,” Fritz adds, “and they’re not in it for the limelight. Their only goal is to let us know they appreciate our service.”

Fritz received the Medal of Honor for leading his vastly outnumbered platoon though an intense firefight in the Binh Long Province of South Vietnam on January 11, 1969. When his armored column encountered crossfire during an ambush, Fritz, then a first lieutenant, was seriously wounded. Realizing that his platoon was in danger of being overrun, Fritz climbed atop his burning vehicle and shouted orders, establishing a defensive perimeter for his remaining comrades. Under heavy fire from opposing gunners, he ran from position to position, repositioning his men, assisting the wounded, distributing ammunition and providing encouragement. He manned a machine gun to break the assault and then led another counterattack carrying only a pistol and bayonet.

Don “Doc” Ballard, a former Navy hospital corpsman second class and 1970 Medal of Honor recipient, attends Gainesville’s festivities every year. His favorite aspect is visiting with the kids, but his annual presence also stems from a profound sense of responsibility.

On May 16, 1968, Ballard ran across a fiery battlefield in the Quang Tri Province of South Vietnam to tend to a wounded comrade. He then instructed four Marines to move the wounded soldier to safety when an enemy soldier approached, threw a grenade and began shooting. Ballard shouted at the Marines to take cover then threw himself on the grenade. When it failed to detonate, Ballard got up and began helping other wounded Marines, saving at least a dozen lives.

Ballard, who lives in Kansas City, Missouri, says he doesn’t attend Gainesville’s Medal of Honor events for the ones he saved or the ones who survived the war. “When I’m here, I wear the medal for the guys that paid the ultimate price,” says Ballard, who retired from the Kansas National Guard as a colonel. “I’m sure any of them would change places with me in a minute. I wear the medal for them because I know they would do the same for me.”

For Fritz and Ballard, the Texas city’s Medal of Honor program celebrates everything that’s right with America. “It’s about community and respect,” says Fritz. “The citizens of Gainesville make you feel like you’re part of the family.”

Hosting the veterans has changed the folks in Gainesville, too. “It’s made each of us evaluate our own sense of patriotism,” Richardson says. “It’s made us realize that patriotism is not generational. It’s a process, an everyday process of being thankful for those who have served and those who will serve.”

Ballard says he feels the celebration sends a great message. “We need to impart our values to our kids,” he says. “The whole program is dedicated to real heroes—not guys who hit home runs or make the tough shots on a basketball court—but guys that really laid it on the line, for their country and for the guy next to them.”

——————–

E.R. Bills of Aledo has written ‘Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious’ (History Press, 2013).