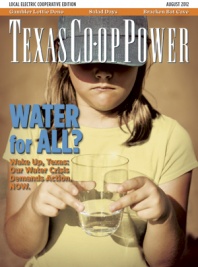

Editor’s note: In this special issue, we explore our most precious resource—water. Starting with this introduction, we take close-up looks at the sobering realities facing Texas. It’s no longer enough to simply be concerned about future water supplies, state officials and conservationists say. Drastic action is required now, starting with conservation, education and long-range plans. Is there hope? Yes. But it takes everybody working together. Every drop counts.

‘Why worry? they said. It would rain this fall. It always had. But it didn’t. And many a boy would become a man before the land was green again.’

From The Time It Never Rained, by Elmer Kelton

That strange-looking contraption behind Robert Lee Mayor John Jacobs is a spillway—something that hasn’t been needed in a long time at E.V. Spence Reservoir, which sits almost empty in the wake of severe drought. The blue floodgates on the bottom of the spillway stand about 90 feet above what now is dry ground. Robert Lee came close to running out of water, and other West Texas cities face the same threat. ‘We were just the canary in the coal mine,’ Jacobs says.

Woody Welch

On a warm April morning north of San Angelo, thick yellow wildflowers cover roadside ditches like luxurious rugs. But as State Highway 208 winds toward the tiny town of Robert Lee, the eye snags on the inescapable: charred, dead trees standing sentry on hills still bald from vicious wildfires a year ago.

Inside City Hall, Robert Lee Mayor John Jacobs steps out of his office, offering a cheery, weatherproof grin beneath his horsehoe moustache. Yes ma’am, come on in. You think he’d be sick of the drill by now: For the past several months, major media outlets—PBS, the Wall Street Journal, MSNBC, etc.—have been rolling into town to gawk at the cracked, parched ground of the huge, almost-empty E.V. Spence Reservoir that’s no longer helping supply water for half a million people, including the 1,050 residents of Robert Lee.

But Jacobs, a gentleman who removes his cowboy hat indoors, patiently chauffeurs visitors around town. He even let a German TV crew see that he wouldn’t get trampled while slinging out range cubes for his cattle.

Like Charlie Flagg, the fictional protagonist in The Time It Never Rained, the 66-year-old Jacobs is a multigenerational rancher with deep West Texas roots. Both men call San Angelo the nearest big city. And both understand a fundamental truth: Water is life.

His cattle sold, Flagg’s character resorts to “burning pear,” burning the spines off prickly pear cacti for his Angora goats to eat during the prolonged drought of the 1950s.

During that same real-life drought, Jacobs was about 6 when he learned to drive, working the clutch and stick shift on a Ford pickup. His father, walking behind the vehicle, burned pear for his hungry cattle with a handheld torch connected by hose to a propane tank in the pickup bed.

Decades later in 2011, when record heat, fire and drought scorched the land, Jacobs didn’t bother with the practice. Cacti pears were so dry and shrunken, he says, his cattle wouldn’t have been interested.

Jacobs, who has downsized his herd from 80 to 30 mother cows, has endured his share of drought. But, he allows, he’d never seen, or heard, anything like last year when big rocks—pow! he says, remembering the sound—exploded in pastures during hellishly hot wildfires. And nobody, he says, ever dreamed of seeing the day when E.V. Spence—which at capacity holds 488,760 acre-feet, almost 160 billion gallons—would sit drained and useless, like a swimming pool in which somebody pulled the plug.

The Colorado River Municipal Water District, which owns and operates E.V. Spence, stopped pumping from it in September 2011. The district permitted Robert Lee, a longtime customer, to keep drawing water from the reservoir on its own, but by early 2012, the remaining water was too shallow and salty for pumping.

So here it is April, and on this day, Robert Lee is pumping and treating water from Mountain Creek Lake—essentially a large stock tank in town, built around 1950—that once met all of Robert Lee’s water needs. Needless to say, residents are conserving water. Nobody’s yard is green. And everybody’s counting the days until a 12-mile emergency water pipeline from nearby Bronte is connected.

Yes, Jacobs says, E.V. Spence Reservoir is a depressing sight. But he ruefully smiles and grabs his hat and pickup keys. Come on. I’ll drive you out there.

From an overlook, it’s hard to believe that the sprawling basin below, slowly being overtaken by tumbleweeds and salt cedar, was once a full, artificial lake. Over there, Jacobs says, gesturing toward a nearby cliff, is where his two sons, as teenagers, used to jump into the reservoir, plunging into water so deep they never worried about hitting bottom.

Today, from that same cliff, it’s almost a straight 100-foot-plus drop to a dry beach of scrub brush and rocks. You could rappel down and start walking all the way across the bottom of the barren lake bed between shallow pools in which ducks nonchalantly swim.

Jacobs stares across the desolate expanse, remembering bass fishing tournaments held here and boats so thick on the water you couldn’t stir ’em with a stick. Now the reservoir is a skeleton, with its bones—reddish, rocky earth—exposed. “That,” a grim-faced Jacobs says, “is the picture of drought.”

‘We’re Running Out of Water’

And this is the picture of fear: On May 21, Mountain Creek Lake was down to about its last 8 inches. On May 22, Robert Lee—desperately pumping the last drops from what had become an emaciated pond—started receiving piped water from its neighbor, Bronte.

“We cut it close,” Jacobs dryly understates. What’s happening in West Texas is a wake-up call: Water shortages, say state water officials and conservationists, could happen anywhere in the state. We’re all in the same boat. “People tell me to quit talking about it,” Jacobs says, “but we’re running out of water.”

The Robert Lee mayor gets no argument from the Texas Water Development Board, whose 2012 state water plan (see “Water for Texas,” Page 16) sounds the alarm: During times of drought, the state does not have enough existing water supplies.

It’s an ominous projection on many levels, including this one: More than 11,000 megawatts of Texas electric power generation rely on cooling water from lakes and reservoirs at historically low levels, according to a 2011 drought impact report from the state comptroller’s office. Without sufficient rainfall, that capacity could be jeopardized.

“You can’t run a modern society without electricity,” says State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon, who compares Texas’ water woes to the calm before the 2005 storm of Hurricane Katrina, when experts agreed that New Orleans’ levee system was insufficient—and no one reinforced it. “Nobody’s willing to do it until, whoops, catastrophe,” he says.

“And that’s what it might take for this state,” Nielsen-Gammon continues. “We might actually have to have an urban area run out of water or have major blackouts for people to recognize that this is something important enough that it has to be dealt with, not just on paper, but in practice.”

‘Drought Happens’

Perhaps nothing better illustrates water officials’ frustrations than the tongue-in-cheek “hydro-illogic” cycle being circulated at closed-door meetings. The chart describes people’s perceived attitudes toward weather: drought—concern; severe drought—panic; rain—apathy.

As of June, much of the state had received above-average rainfall for the year, but some of the highest amounts fell in the Dallas, Houston and San Antonio metropolitan areas, Nielsen-Gammon says, tending to steer public perception toward a false conclusion: Everything is nice and green here, so the drought must be over.

Yet in early summer, more than half of Texas remained in drought conditions, with three areas suffering the most: the Big Bend region, the extreme western portion of the Panhandle, and a triangle formed by Abilene, Childress and Lubbock. You’d better believe those people know where water comes from. Meanwhile, there are those who don’t have a clue:

• Years ago, in response to the TWDB’s annual water-use survey, one mayor mailed back his responses with a politely stated letter: “We do not use ground or surface water. Our water comes from a water tower.”

• In 2011, as Texas’ drought became severe, the TWDB received several phone calls from individuals wanting to know—seriously—where the state’s water pipeline was and how they could tap into it.

If only it worked that way—someone could just wave a magic wand over Texas’ driest spots and render them lush and green. Instead, we’re left with cold-hearted science: Most water planners use what’s considered the state’s drought of record—a six- or seven-year period starting in 1950, depending on location—as a worst-case scenario. But a study published last year in the Texas Water Journal is making officials rethink that conclusion. Research of tree rings—bald cypress in South Central Texas, Douglas fir in West Texas and post oak in Central Texas—indicates that several extended droughts were longer and/or more intense than the 1950s dry spell.

Further, note the study’s authors—from the University of Arkansas, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and The University of Texas—Texas has suffered severe decadal-scale droughts at least once a century since the 1500s. The authors don’t mince words: “When water managers consider past droughts, population growth, and climate change, it becomes highly probable that the future poses unprecedented challenges.”

In other words, even as we put the horrific images of 2011 behind us, it can still get worse. Or, as Nielsen-Gammon says: “Drought Happens,” the slogan the state climatologist jokes about putting on a T-shirt.

To some urbanites, the idea of a reservoir—or a town—running out of water is simply unfathomable. By way of education, Nielsen-Gammon likens drought to a child maturing into adulthood: The longer an extreme dry spell lasts, the more strength it gains. It takes years for reservoirs to fill up, and it takes years for them to go down. In semi-arid areas, such as West Texas, reservoir levels can drop each successive year, until finally, if the drought doesn’t break, they hit bottom.

To be fair, plenty of Texans comprehend drought. And many people understand that, depending upon where they live, water comes from aquifers, rivers, reservoirs and, of course, the sky. But, as Robert Lee’s Jacobs reminds: “Only the good Lord can make it rain.”

As San Antonio water officials and city council members look on, Superintendent Art Ruiz explains how El Paso’s Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination Plant converts brackish water to fresh drinking water. The concentrate—the byproduct waste produced during desalination—is piped underground to wells and injected 4,000 feet deep into dolomite rock formations that prevent migration to fresh aquifer water. The facility is drawing global interest, including from San Antonio, which plans to bring a desalination plant online in 2016.

Woody Welch

Water from Water

Flying into El Paso, gazing out the window at the desert floor coming into sharper view, it suddenly seems unwise to relinquish a plastic cup of ice as we start our descent. Save for scattered shrubs and cacti whose coloring blends with the chalky-brown dirt below, the bleak terrain offers few signs of life. No green. No water for miles and miles and miles.

As the plane’s landing gear unfolds, and the flight attendants swoop down the aisle to scoop up drinks, finished or not, it’s hard to let go. Just looking at the desert is enough to make one thirsty. But a quiet chuckle comes: As a visitor to El Paso, it’s easy to succumb to hyperbolic thinking. Water, after all, is what brought this reporter here.

Water. Cold, precious water that’s being saved, reclaimed, protected and transformed in this far West Texas city tucked into the northern corner of the Chihuahuan Desert where the average annual rainfall of 8.8 inches is more than 20 inches below the norm around much of the state.

Yet in what approximates a modern-day miracle, El Paso officials proudly point to the statistics: Since 1991, when its water conservation ordinance was enacted, El Paso projects it has saved more than 231 billion gallons of water. And through a diverse conservation and water management program, the city estimates it is saving almost 19 billion gallons a year.

No, you can’t change the desert. But, says Ed Archuleta, president and CEO of the El Paso Water Utilities Public Service Board, you can change the culture. What that meant in 1989, when Archuleta arrived in El Paso to oversee the department, was the start of an aggressive conservation program and a 50-year water management plan designed to protect the city’s primary water sources: the Hueco and Mesilla bolsons, or aquifers; and the Rio Grande, whose flow relies on seasonal snowmelt from Colorado and New Mexico mountains.

That foresight has yielded remarkable results: Per one of the city’s slogans—“Water shouldn’t only be used once!”—El Pasoans use more than 2 billion gallons of reclaimed effluent (treated wastewater) each year, including for industrial use, golf course and residential property irrigation, and power-generation cooling at El Paso Electric.

And then there’s a magnetic message—making water from water—that’s attracting researchers from around the globe, including desert countries such as Saudi Arabia, to the $91 million Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination Plant. The world’s largest such inland facility has the capacity to produce 27.5 million gallons of freshwater a day, boosting the El Paso Water Utilities’ daily freshwater production by 25 percent.

Hutchison, a U.S. senator who lives in Dallas, helped secure $26 million in federal funding for the plant, the largest project of its kind involving the U.S. Department of Defense and a community. It serves El Paso, which owns the facility, and Fort Bliss, an Army post that owns the land. In 2011, more than 734 million gallons from the plant were blended into Fort Bliss’ freshwater supply.

Through reverse osmosis, a process in which pressurized raw water passes through fine membranes, separating salts and other contaminants, the plant turns salty brackish water pumped from the Hueco Bolson into drinkable water. The permeate, the desalted water, is blended into daily freshwater supplies.

The concentrate—the water containing everything removed during desalination—is pumped 22 miles underground to solar-powered deep-well injection sites on Fort Bliss property surrounded by open desert.

It’s a win-win-win situation: For El Paso, for Fort Bliss and for the Hueco Bolson, in which pumping captures the flow of brackish water toward freshwater wells. The aquifer was dropping 1 1/2 to 3 feet a year by the early 1990s. Now, incredibly, despite drought and little rain runoff, it is stable and at 1960s levels thanks to conservation efforts, city officials say.

“Show me an aquifer that’s been depleted and is now recovering or at least stable,” Archuleta says. “I don’t think you’ll find too many.”

On a mid-April morning inside the desalination plant, the pleasant hum of electric generator units sounds like a waterfall. Standing beside rows of gleaming, stainless steel-encased membranes, Plant Superintendent Art Ruiz fills two paper-cone cups beneath spigots. “Go ahead and tell me what it tastes like,” he says.

Timid sip. Hmmm … it’s uh … pretty good. Is this a trick?

Ruiz smiles, handing over the second cup. “Now, with your finger, taste that.” Whoa! WAY salty. Yep, that’s the concentrate. And the first cup was the permeate. Amazing. It tasted just fine.

Innovation. Conservation. Reclamation. Education. Diversification of water strategies, Archuleta says, is what keeps El Paso afloat. Too many cities, he muses, suffer from short-term thinking: The drought’s over, it’s raining, we can put water issues on the back burner. “If you continue that fallacy, it’ll burn you after a while,” he says.

Take a lesson from the water experts: “El Paso,” Archuleta says, “always has a plan.”