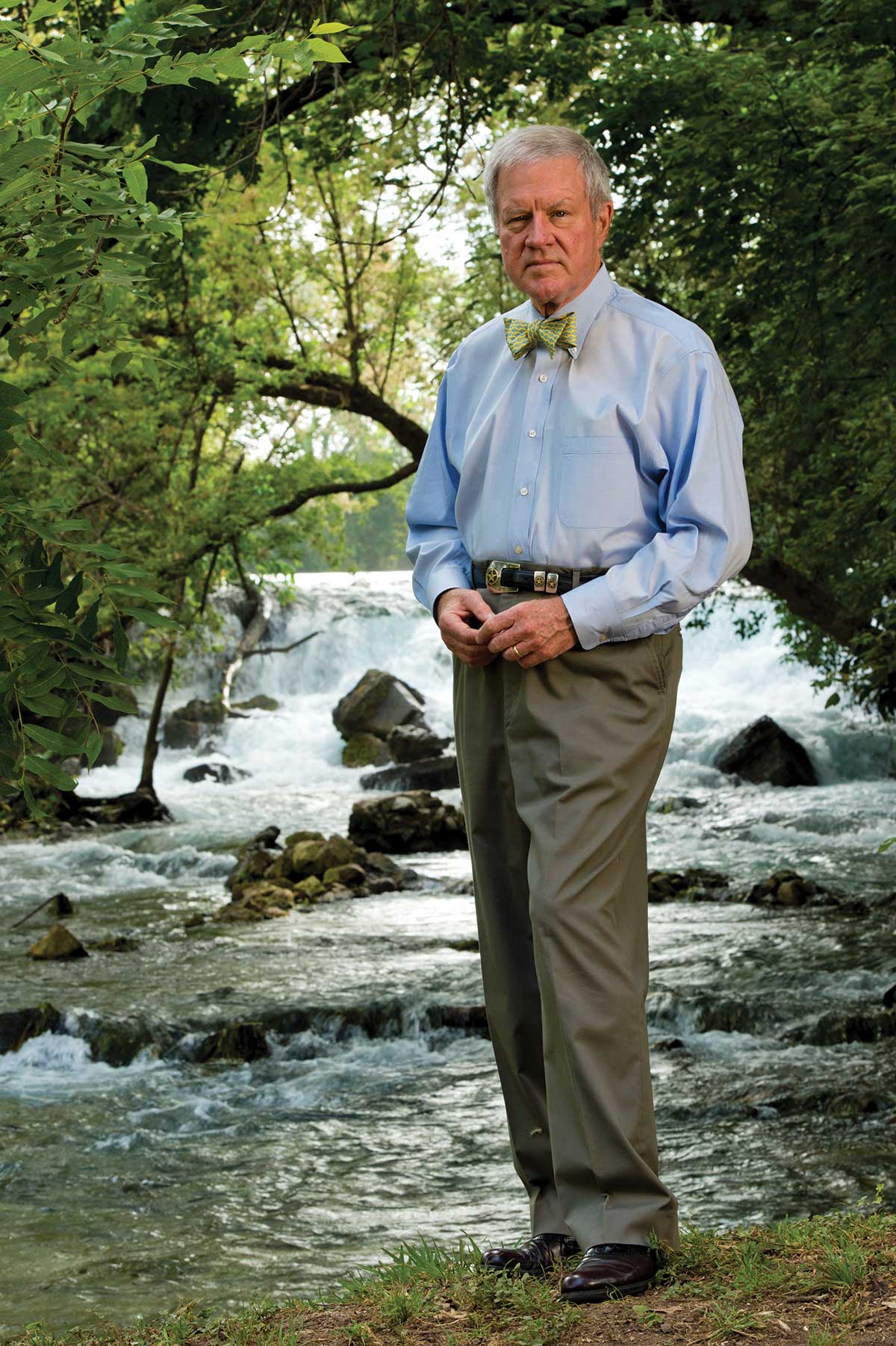

Not long ago, I spent an afternoon with David Baker, who lives near the headwaters of Cypress Creek in Hays County at a lovely spring known as Jacob’s Well. Baker, originally an artist, has spent most of his adult life fighting to protect “the well,” as he calls it, and to keep it flowing and nourishing the creek, one of Texas’ most beautiful streams.

On the day we walked its banks, the creek was dry, and Jacob’s Well had stopped flowing for only the second time in history. The first time was in 2000, and the trend is ominous. For Baker, the possibility that the next generation of Texans will not have the opportunity to experience this iconic spring and many others throughout the Texas Hill Country is unimaginable.

It could happen.

Though the recent drought has helped to focus the attention of Texans on our water problems, to knowledgeable observers, they have been developing for a long time. “You can go without cable TV. You can even go without air conditioning, but you can’t go without water,” says Tom Mason, former general manager of the Lower Colorado River Authority, one of our state’s largest water providers.

The bottom line is that our population here in Texas is expected to almost double in the next 50 years or so, and we have already given permission for more water to be withdrawn from many of our rivers and lakes than is actually in them.

Our vast system of reservoirs was built following the last big drought, the one we call “the drought of record” in the 1940s and 1950s. At that time, most Texans lived in small towns supported largely by agriculture or on farms and ranches. Thus, the drought affected almost everyone directly. As a result, we got serious and embarked on a massive reservoir construction program and initiated a water planning strategy that we still rely on today.

The 2012 edition of the state water plan from the Texas Water Development Board was compiled by 16 regional planning groups across the state and has a price tag of $53 billion for new water infrastructure. We clearly need to invest in providing water for our future. But even if we could come up with that kind of money, the reality of other noninfrastructure challenges suggests that we cannot simply build our way out of this predicament.

The stream along which Baker and I walked that day eventually flows into the Blanco River. The Blanco originates in Kendall County and winds its way to the Guadalupe River in Hays County. On the way, much of its flow goes right back into the ground from the riverbed. The water runs underground to Jacob’s Well, where it comes back to the surface, forming Cypress Creek, which flows down through the villages of Woodcreek and Wimberley and back into the Blanco. The reality is that obtaining a permit from the state to remove water from the river today would likely be impossible—but if you wanted to drill a hole and take it out of the ground above Jacob’s Well, you would have little or no restrictions to keep you from doing so.

Unfortunately, Texas law treats the same water differently depending on whether it is on the surface or underground. This practice is unsustainable and exacerbated by a recent Texas Supreme Court ruling, which declared that groundwater is the property of private landowners.

As stewards of more than 95 percent of the landscape in Texas, private landowners do have a huge role to play in our water future, and they are not getting much help. Texas loses rural and agricultural land faster than any other state, and this continued fragmentation of family lands is irrevocably impairing the function of our watersheds and aquifer recharge zones, as well as increasing nonpoint source pollution, which is runoff from agricultural fields, highways, parking lots and an increasingly paved-over countryside.

We waste too much water.

At home, we use as much as 70 percent of our household drinking water to irrigate our lawns, and much of that is wasted. Before the water even gets to our residences, many Texas cities and water utilities lose up to 25 or 30 percent of their water through leaking water mains or otherwise poorly maintained distribution systems. The cheapest way for us to provide more water for the future is to begin using it more efficiently.

In this regard, most water rights in Texas are dedicated to agricultural use for irrigation, and much of this use remains antiquated and inefficient. The inefficiency magnifies a conundrum: While so much of our water is committed to agriculture, a sector of our economy that is basically flat, municipal growth is booming and thus producing the greatest future demands for water.

Finally, though the Legislature in 2007 established a process for protecting the aquatic ecosystems of our rivers, streams, bays and estuaries by requiring “environmental flow” standards for each, implementation of the law has been spotty at best. Without greater attention to the freshwater requirements of the environment itself, our inland aquatic ecosystems and extraordinary coastal resources are increasingly impaired.

Against this sobering backdrop, we can celebrate some real successes where water is concerned. Our rivers and streams are demonstrably cleaner than they were a generation ago, thanks to passage and implementation of the Clean Water Act. In the area of water conservation, the cities of San Antonio and El Paso have lowered their consumption of water per capita by a full 40 percent. On the landscape, the cities of Austin and San Antonio and Hays County and other local governments have approved hundreds of millions of dollars in bonds to create conservation easements on private lands in important watersheds and recharge areas.

The bond money is used to compensate landowners in exchange for their agreement to a legal covenant that limits development. The farmer or rancher retains ownership of the land, and a vital resource for the community is protected.

Back along Cypress Creek at this time of year, insects are hatching and swarming along the shore. If you are lucky, you can observe the native sunfish slipping up to the bank and batting vegetation with their tails, knocking their prey into the water so they can feed. Such experiences can only leave one with a deep sense of respect for the living freshwater of Texas and the understanding that we are its stewards on behalf of both the economy and the environment of future generations.

Water is life.