In the first half of the 20th century, color barriers in America were repeatedly broken by black athletes. Jesse Owens was the star of the 1936 Olympics in front of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Berlin. The Brown Bomber, Joe Louis, reigned as the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1937 to 1949 and was a national hero after defeating German fighter Max Schmeling in 1938. And Jackie Robinson sent shockwaves through baseball in 1947 when he broke into the major leagues.

Even before African-American athletes became household names by eclipsing racial milestones in sports, a group of students from Wiley College in Marshall were making similar, if not just as dramatic, inroads—not in sports, but in the arena of collegiate debate.

“It’s amazing their story is so little-known,” says Lloyd Thompson, professor of social sciences and history at Wiley. “They were phenomenal.”

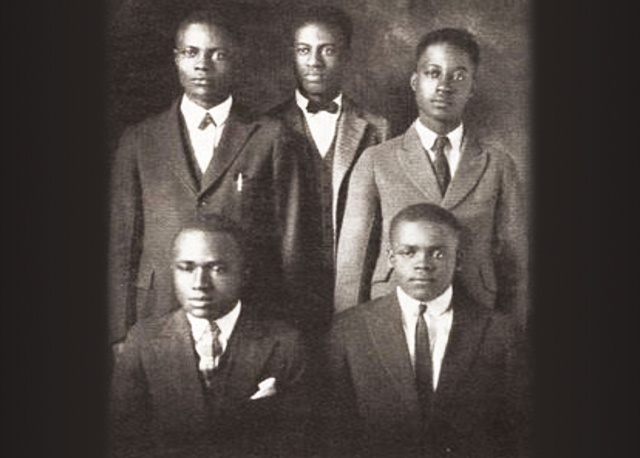

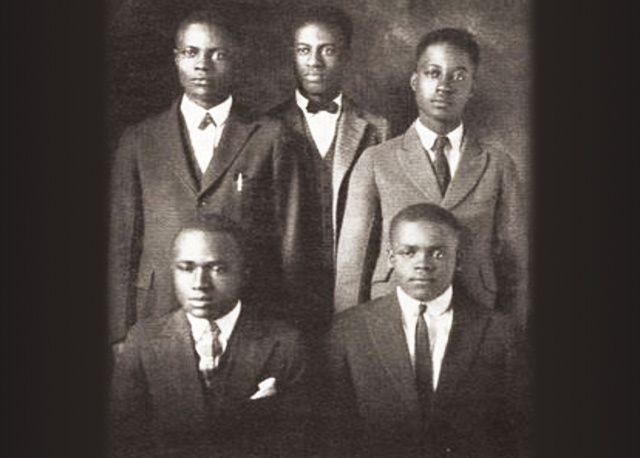

In the fall of 1923, Melvin Beaunorus Tolson took a teaching job at Wiley, a small, all-black college where he wore many hats. Besides teaching English, he wrote poetry, founded and directed a local theater troupe and coached football. Then, on October 28, 1924, he founded the Forensic Society of Wiley College.

Wiley’s Forensic Society became Tolson’s passion, and he taught aspirers to the debate squad that points of view contained no intrinsic truth. Wiley debaters were not simply taught to defend their own individual, heartfelt opinions or beliefs—anyone could do that. Wiley debaters were pushed outside their personal and philosophical comfort zones and forced to win arguments from both sides, lofty or low, seemingly correct or incorrect. They analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of pro and con stances on an issue and then explored ways to bolster, mitigate or refute the premises and conclusions of each side.

Tuesday and Thursday nights at the Tolson house—where members of the debate team gathered to sharpen their cognitive wares—were not for the faint of wit. The Tolson living room became a philosophical shark tank where opinions were solicited, offered, interjected, dissected, rejected, resurrected, conflated, berated, restated and occasionally perfected. Tolson worked to refine his debater’s elocution and delivery. No superfluous gesture, distracting tic, stalling pause or monosyllabic “uhhh” or “well” was safe. Tolson pounced on them like a hawk, cutting them from each team member’s oratory.

Surprisingly, some of the debate topics of the day easily could be substituted for the pressing issues of today. During the 1934-35 debate season, forensic contests were based on four questions: 1) Should the international shipment of arms and munitions be restricted? 2) Should the incomes of presidents of corporations be limited? 3) Should health care be available to all at public expense? 4) Does social planning fall under the purview of the federal government?

Tolson required every Wiley Forensic Society member to read hundreds of books, journal essays and magazine articles on history, government, economics, literature and sociology. With their growing awareness and polished dialectic skills, Tolson’s polemicists staked out intercollegiate debate as their baseball diamond, cinder track or boxing ring and began pummeling their opponents.

In more than 100 debates from 1930 to 1940, they lost one competition. After they dominated all the historically black colleges, including Bishop, Fisk, Howard, Morehouse, Tuskegee, Virginia Union, Knoxville and Wilberforce, they scheduled debates with white colleges.

The national forensic organization that governed collegiate debate competition in America was called Pi Kappa Delta, and it restricted participation in events to white students. Tolson formed Alpha Phi Omega to serve historically black colleges, and Wiley scheduled contests with white colleges as unofficial, no-decision affairs.

In early 1930, the Wiley forensic team matched intellects with law students from the University of Michigan, becoming one of the first teams from a black college to debate a white college team in America. The event was held at the African-American-owned Seventh Street Theater in Chicago because most white-owned venues prohibited racially mixed audiences. In March 1930, Wiley became the first black college to debate a white university in the South, contesting Oklahoma City University at Avery Chapel in Oklahoma City.

The interracial debates were controversial, but Tolson considered them more unifying than divisive. “When the finest intellects of black youth and white youth meet,” Tolson later wrote, “the thinking person gets the thrill of seeing beyond the racial phenomena the identity of worthy qualities.”

Most of the Wiley Forensic Society’s exploits failed to make local or state newspapers because Wiley was an all-black institution. But with coverage or not, under Tolson’s guidance the Wiley Forensic Society became a polemics powerhouse, with each successive debate squad as formidable as the preceding, dominating teams from institutions three, four and five times their enrollment. They did this while traversing the Jim Crow South on shoestring budgets and circumnavigating “whites only” accommodations and restaurants. By the mid-1930s, Wiley was being called the “Harvard West of the Mississippi,” and it was then that the Great Debaters made their mark.

During the 1934-35 debate season, Wiley steamrolled their usual opponents and then set out on what Tolson called the Interracial Goodwill Tour to debate a number of colleges on their way to California to challenge the reigning Pi Kappa Delta national champion, the University of Southern California.

In the early spring of 1935, they were well-received in Fort Worth when Texas Christian University made history by becoming the first white college in the South to invite a black college team onto its campus for a debate. Wiley debaters Hobart Jarrett and Cleveland Gay handily defeated the recently formed Forensic Frogs and, afterward, the crowd rushed the stage to shake their hands and congratulate them. Tolson later remarked that TCU “had a splendid team, and we were never received more agreeably anywhere.”

On March 22, 1935, Jarrett and Gay defeated Willis Jacobs and John Kennedy from the University of New Mexico at Texas’ El Paso Negro High School. Next, the Wiley College debaters faced a team from San Francisco State Teachers College before heading to Los Angeles to face USC.

USC put the Wiley team up in dorm rooms, and Tolson subsequently confined them there. USC’s speech department was larger than Wiley College’s entire campus, and Tolson reportedly didn’t want his team intimidated.

On April 2, 1935, Wiley debaters Jarrett and Henry Heights locked minds with the Southern Cal debaters in front of a crowd of 2,200 at Bovard Hall. Based on interviews and reports of the event, Jarrett and Heights impressed everyone with their erudition and wit and vanquished the nation’s pre-eminent white collegiate debate team.

As the contest was a no-decision affair, Wiley College was never proclaimed national champion by Pi Kappa Delta, but they did earn the title of “The Great Debaters,” and their ascent to the apex of collegiate intellectualism was no less amazing or inspiring than the accomplishments of the era’s great black athletes.

“Given the temper of the times in which they lived,” Thompson says, “their success is hardly believable. To hail from a tiny black college in East Texas and reach the pinnacle of intercollegiate debate—it was just an incredible achievement.”

In 2007, “The Great Debaters”—a movie directed by and starring Denzel Washington and produced by Oprah Winfrey—hit theaters and introduced the story of the legendary Wiley forensics program to the American public. Washington subsequently donated $1 million to Wiley College to re-establish its forensics program, and today it’s back to its winning ways.

In the 2013 debate season, the team made history again when it became the first historically black college to officially earn a national forensics championship. Wiley claimed an individual national title at the National Christian College Forensics Association Tournament held in Siloam Springs, Arkansas, this past March.

——————–

E.R. Bills is a writer from Aledo.