For years now, all eyes have been on the bees.

In the mid-2000s entire colonies of worker bees started disappearing suddenly and mysteriously, raising alarm bells around the world. Since then, there has been serious concern for the insects we depend on to pollinate our crops and native flora. Bees are up against a whole host of threats, including habitat destruction and fragmentation, invasive parasites, and extreme weather.

But things might finally be looking up for honeybees. In the U.S., honey production was up 11% in 2023 after three years of decline, according to the Department of Agriculture.

That’s due, at least in part, to the many dedicated defenders of these critical pollinators. Across Texas a growing movement of beekeepers, educators and researchers are working to save the bees. One such defender—Juliana Rangel, a professor of apiculture who runs the Texas A&M University honeybee lab—says those efforts are starting to pay off.

The biggest threat facing the bees, Rangel says, is the varroa mite, a tiny parasite that feeds on bees and spreads viruses among colonies worldwide. Despite measuring just over a millimeter, the pests have devastated U.S. honeybee populations as they’ve spread since the late 1980s. Some insecticides are effective against varroa but can also have negative effects on bees.

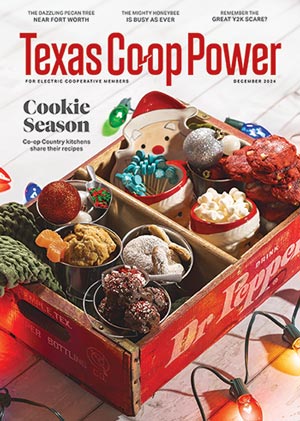

Busy bees at Two Hives Honey in Manor.

Eric W. Pohl

Making matters worse, increasing urbanization has left wild and managed bees with less forage.

Bees also must contend with extreme weather amid a changing climate. The February 2021 winter storm in Texas impacted bee populations unequipped for the cold and delayed the spring blooms they rely on for food. In addition, increasingly hot summers and droughts have left many bees starving. Beekeepers can keep them alive, but they’ll struggle in the heat, with poor nutrition leading to no honey yields.

Against these threats, it’s impressive that bees can survive in the wild. While beekeepers keep honeybees almost exclusively, native wild bees often live secluded, in nests, making them much harder to study. But they face many of the same challenges as their managed counterparts.

“I love feral colonies because they are kind of like a beacon of not just diversity but also resilience against all of these issues,” Rangel says. “If they’re alive, it’s because they’ve been able to survive on their own.”

Luckily, not all bees have to do it on their own. Beekeepers across the state dedicate themselves to the pollinators.

Jaquier captures a sample of honey.

Eric W. Pohl

Suzanne Truhlicka, a Lyntegar Electric Cooperative member who lives in Tahoka, just south of Lubbock, was hooked after a neighbor took her along for a hive removal in 2019. “I just became addicted to bees,” Truhlicka says. “The bees are like therapy to me. They’re a challenge, every day.”

She now maintains 12 hives and sells honey and beeswax products online and at local shops through her business, Flying Fancy Bees. She’s one of many Texans who have picked up the trade in recent years. In fact, the number of farms with bees in Texas more than quadrupled from 2012 to 2022, according to the USDA’s Census of Agriculture. Texas had 8,939 farms with bees—more than twice as many as the next highest state, Ohio.

One leading contributor to Texas’ honeybee craze is a 2012 state law that allows folks with 5–20 acres of land to get a property tax break under an agricultural exemption if they keep bees.

That tax break was what originally prompted Susan Allen to put hives on her North Texas property, deciding that tending bees was going to be a whole lot easier than maintaining the hay the land had been used for. But what started as a smart financial move quickly grew into a passion as Allen, a Grayson-Collin Electric Cooperative member, became more and more involved in beekeeping, connecting with other local beekeepers through the Grayson County Beekeepers Association.

The more Allen learned about bees, the more she was invested. “They’re just so stinking smart,” Allen says. “They’re fascinating. That’s what keeps me going. It’s just learning more and more about them.”

Honey production in the U.S. was up last year even as bees face a range of threats.

Eric W. Pohl

Beekeeping clubs exist all over Texas, gathering in churches, community centers, restaurants and homes to educate, discuss challenges and collaborate.

Best friends Rosie Lund and Meredith Pace started their honey and beekeeping supply business, Apis Supply, in 2023 and quickly realized they needed a bee club in their neck of West Texas, where high winds and dry weather make keeping bees particularly tricky. The duo helped organize curious beekeepers into the Permian Basin Beekeeping Association, which now meets monthly in Seminole.

“It’s a family, really,” says Pace, a Lyntegar EC member. “We all just kind of support each other. It’s like, ‘Oh, hey, I have an extra frame,’ or ‘I have an extra box,’ until you can get stuff in the mail because everything takes a week to get here.”

Much like the community inside a hive, the community of beekeepers depends on each other. And they depend especially on people like Tara Chapman, whose beekeeping venture goes well beyond honey production, aiming to get more people informed and excited about bees.

Chapman took a beekeeping class in 2013 while looking for a new career after 10 years at the CIA. She became fascinated with bees and decided to trade war zones for worker bees, starting with just two hives maintained by her and a friend. Her operation has grown to more than 300 hives at Two Hives Honey in Manor, just east of Austin.

Atlas, owner Tara Chapman’s son, helps with the smoker.

Eric W. Pohl

Chapman has become focused on beekeeping education.

Eric W. Pohl

Chapman doesn’t get to spend as much time “in bees” as she used to but now focuses on beekeeping education. In addition to tours of the honey ranch, honey tastings and beekeeping classes, Two Hives offers a six-month hands-on “beek” apprenticeship program. Last month Chapman published For the Bees: A Handbook for Happy Beekeeping.

“Beekeeping is the most nuanced form of ag there is,” she says. “I will argue to my death that that is true, and it’s not totally intuitive to everybody.”

Chapman set out to teach people about the “bananas” world of bees, making sure they understand basic bee biology first. Inside each hive is an entire society, she explains, with a queen at the center. But the queen, while important, isn’t really in charge. Honeybees make decisions democratically, communicating through pheromones and “waggle dances.”

“It just so defies logic of how humans live and exist,” she says. Understanding the foreign world of bees is one of the things that can make keeping them so challenging.

A collection of hives in September at Two Hives Honey. The smoke keeps the bees calm while keepers perform hive inspections.

Eric W. Pohl

“I’ve made every mistake, and I think it’s why my greatest asset is my ability to teach beekeeping,” Chapman says. Those mistakes have included an incident in which an improperly secured box resulted in roughly 50 pounds of spilled honey in the back of Chapman’s truck.

Luckily, she says, bees will quickly come to take care of any honey that’s just sitting there for the taking, but “while they’re taking care of it, it’s going to be a terrifying sight for the layman that happens to be walking by your driveway.”

Chapman’s and others’ efforts haven’t been in vain. Rangel says the increased awareness and interest have been important and that honeybees are doing better now than when the public first learned about collapsing colonies—though it’s too soon to say they’re in the clear. Honeybee numbers can fluctuate year to year as environmental factors change, but Rangel says there’s been a trend of about a 1% increase in the U.S. managed population each year.

“In the last 15 years, the number of studies on honeybees and honeybee health have grown exponentially, which increases our understanding of all the issues that they face,” she says.

“Increased awareness by the public and the farming community, I think, is what’s mostly helping.”