Snakes never stood much of a chance.

Even in the early pages of the Bible, the serpent was cursed above all other animals and dealt a troublesome fate: “You will crawl on your belly, and you will eat dust all the days of your life.”

If that lowly lot wasn’t bad enough, from then on they have found themselves on the wrong end of gardening tools and weaponry.

And still they thrive, especially in Texas—home to more than 100 species and subspecies of snakes, including 15 that are venomous.

Their greatest allies, it turns out, are men like Nathan Hawkins and Brett Parker, who themselves crawl on their bellies to remove and safely relocate snakes that encroach on humans’ domain, particularly from crawl spaces under homes.

“There are a lot of rattlesnakes here,” Hawkins says. “A lot more than people realize are here.”

Hawkins and Parker own snake removal businesses, both with an ethos of keeping the snakes, usually rattlers, alive and relocating them to remote habitats. They believe keeping the ecosystem intact and educating people about snakes’ role in nature are best for all involved.

The education part can be a challenge.

“A good snake is a dead snake.” Hawkins and Parker hear that almost every day.

“Completely false,” says Hawkins, who owns Big Country Snake Removal outside Abilene. “They’re very important to a healthy ecosystem. And they all deserve life.”

Hawkins, a member of Taylor Electric Cooperative, knows that isn’t what folks want to hear. Most people hate snakes and want them as far away as possible. But Hawkins’ method serves snakes well, helps put food on the table for his wife and young son, and has kept him in business for eight years.

He removed 45 rattlesnakes from under a house in 2019. A story about that ran in The Washington Post and elsewhere, and his video from that job went viral, making him somewhat famous. His biggest job to date is 127 rattlers, collected under a house in Seymour, southwest of Wichita Falls.

He removed 80-plus copperheads from a property between Cisco and Cross Plains in 2023. That was a nighttime job, when the snakes became, for Hawkins, easy pickings as they feasted on cicadas emerging from the ground.

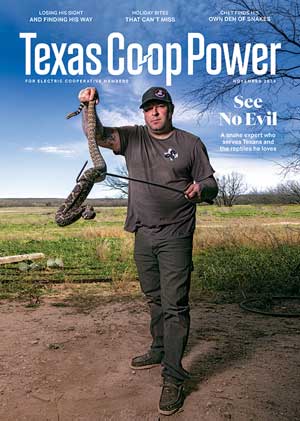

Nathan Hawkins, owner of Big Country Snake Removal, with one of the six rattlesnakes he and a co-worker pulled out from under an abandoned house outside San Angelo. He releases most in a remote pasture, but he also has a collection of some 200, including mambas, king cobras, bushmasters and almost every venomous species in North America.

Russell A. Graves

Hawkins is a self-taught herpetologist whose love of snakes started when he was a kid in the Abilene area. He loved finding and collecting them, and that passion never waned. Today his collection has grown to include about 200 snakes—90% of them venomous.

He spends much of his free time looking for snakes. For vacation, he travels the Southwest in search of varieties of rattlesnakes (there are 23 subspecies in North America). His hobby is not without hazards. He has been bitten by venomous snakes seven times—twice by copperheads, once by a southwestern speckled rattlesnake in Arizona and the rest by western diamondbacks.

“If you’re a carpenter, you’re going to hit your thumb with a hammer at some point, and when you mess with snakes as often as I do, it’s bound to happen sooner or later,” says Hawkins, who is quick to point out he has never been bitten on the job.

He conducts workplace training for folks in the oil and energy industries who spend a lot of time in rugged terrain. He meets annually with Texas Department of Transportation employees to teach them about handling run-ins with snakes. He trains dogs to help them avoid snake encounters. He’ll also visit schools, youth camps and birthday parties.

Hawkins with one of six rattlers found under a house outside San Angelo.

Russell A. Graves

The author very briefly gets to hold a rattlesnake during the photo shoot for this story.

Russell A. Graves

Winter is the busiest time for Hawkins and Parker, who owns Hill Country Snake Removal outside Austin. That’s when snakes become sluggish and enter a state of brumation, similar to hibernation. They gather into dens, including crawl spaces under homes, where they are protected from the weather and where the stagnant air keeps their body temperature regulated.

Though their businesses are about 240 miles apart, Hawkins and Parker sometimes team up for jobs. That was the case in January, when Hawkins was hired to remove rattlesnakes from under an abandoned house outside San Angelo.

Hawkins, who played a season of football at McMurry University, stayed above ground, and the more slightly built Parker put on his headlamp, grabbed his snake tongs and wiggled into the darkness through a small hole in a closet floor.

First came the offensive odor, likely from the raccoons and skunks also living underground. After a bit of cautiously crawling around, Parker found snakes—six of them—resting under a piece of plywood.

Using tongs, Parker handed them one by one up through the floor to Hawkins. They ended up in a covered 5-gallon bucket in the back of Hawkins’ pickup.

After lunch, they headed up to Anson, just north of Abilene, for a job at the home of Kevin and Jolee Karle, members of Big Country Electric Cooperative.

The Karles knew they had snakes. Before hiring Hawkins, Kevin had killed 10 of them with a shotgun. With two horses and a dog, dispatching snakes around his house was a guilt-free decision. “Oh, no,” Kevin says. “I wanted to protect the family.”

The snakes, one or two at a time, were placed into a sealable piece of 4-inch PVC pipe that Parker handed to Hawkins. “There’s still more in here,” came Parker’s muffled voice from deep in the void.

Eventually, the snakes were coming out three or four at a time. It was near dusk when Parker finally emerged, behind snake No. 29.

“We couldn’t believe there were that many under there,” Jolee says. “The way I look at it, I grew up in the country, so the fact that we’re going to have snakes in the country doesn’t bother me.”

But 29 rattlers? Just a foot or two below your bed? “That’s just a part of country life,” she says.

Brett Parker, who helps Hawkins on occasion, owns Hill Country Snake Removal. He’s also a captain with Canyon Lake Fire and EMS.

Russell A. Graves

That part of country life doesn’t sit well with some people.

Sarah McLen leads member services at Big Country EC. She lives about 25 miles southwest of Anson.

She and her husband keep a hoe or shovel at each of their exterior doors and by the door to a workshop. The McLens are not, she notes, big-time gardeners.

“We use the tools for their normal purposes,” McLen says. “We’ve killed multiple snakes in a variety of sizes in just about every area of our yard. We kill the rattlesnakes because they multiply, and we have dogs to protect.

“My husband picks on me because I whack them to pieces! But as far as I’m concerned, the more dead they are, the better!”

Because a good snake is a dead snake.

“It’s very, very common here,” Hawkins acknowledges. “Very common.

In winter, when snakes enter a state of brumation, which is similar to hibernation, Hawkins gets called out to many jobs.

Russell A. Graves

“You just never know where a snake’s going to be,” he says. “You never do.”

Russell A. Graves

“I have absolutely no right to tell somebody how to protect their house, how to protect their pets. If you feel that’s the right thing to do, then go for it. And I’ll give you a high-five.”

Hawkins just wants people to be aware of the bigger picture, and that’s where his mission to educate kicks in. As part of a stable ecosystem, snakes keep rodent populations in check, and they also are a food source for raptors, large mammals and even other snakes. “At least be a little bit open-minded,” he says.

For some people, though, Texas’ snake population feels like it’s of biblical proportions.

“I feel like I probably walk the yard with my ‘weapon’ held high, like Moses did with his staff when he parted the Red Sea,” McLen says.

Meanwhile, Hawkins carries on with the staff of his choosing, snake tongs that he wields with a light touch.

“The only good snake is a live snake,” he says.