In 2004, Blake Shook had been keeping honeybees for only a year when he heard about a swarm in a tree on the McKinney downtown square.

Before an audience of lunchtime onlookers, Blake, then 14, managed to shake about half of the swarm into a bucket from the bees’ 20-foot-high perch. He took them home and added them to his collection of hives. “He’s always been fearless about trying new things,” recalled Lyndon Shook. His father knew little about bees, but Blake was learning fast via a local beekeeping group.

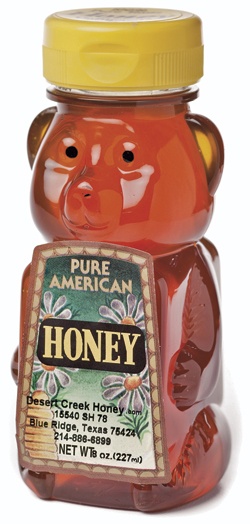

Today, the 20-year-old Blake Shook has more than 500 hives, a small but growing presence on some Dallas-area store shelves for his Desert Creek Honey and enough knowledge of the beekeeping art to teach the classes he attended as a student only a few years ago. He’s decided to turn beekeeping into his life’s work, making this business owner a rare, youthful addition to a field that many say is getting a bit gray.

“As I was going through high school, I was thinking, ‘I love beekeeping,’ ” said Shook, who was homeschooled. “I got excited about it because bees are absolutely fascinating. You learn you can get your own bucket of honey from a beehive, and there’s nothing like tasting the honey the very first time you produced it.”

By the age of 15, Shook was making as much as $10,000 a year from his hobby and taking a big interest in the fascinating nature of honeybee colonies. “I started putting it all back in the business, and by 16 or so I started thinking this could be my job,” he said.

A good student, Shook struggled with the decision to forgo college as he pursued his business interests. But Shook, who started the Desert Creek Honey Co. with two beehives, says he could always take classes online someday if he decides to obtain a degree.

The work varies with the seasons. In the winter, Shook travels among several bee yards and feeds the hives with a mix of sugar and water that works as a nectar substitute when flowers aren’t in bloom. Honey typically is harvested from June through August. The work entails calming the bees by smoking the hives to cover the pheromones, or alarm scent, that the bees secrete; removing the wooden frames that hold sections of honeycombs; uncapping the cells—which means removing the wax caps from hexagonal cavities; and extracting the honey. He does his own bottling, labeling, distribution and sales and expects to hire help as his business expands.

Shook’s growing operation is spread out with hives on his parents’ farm in Blue Ridge, north of Dallas; a partner’s honey farm 15 miles to the south; and several other bee yards in the area. The packing house, or honey house, that Shook built at Blue Ridge is already too small for his commercial ambitions, and he is joining forces with John Talbert, a 72-year-old retired mechanical engineer who has kept bees as a sideline business for 25 years.

Shook’s first honey house was designed for a smaller operation in which honey moves from 5-gallon buckets into bottles and jars. As a commercial operator, he needs to be thinking in terms of forklifts and 55-gallon drums.

“You can tell from the front yard a beekeeper lives here,” said Shook as he pulled his sport utility vehicle into Talbert’s Sabine Creek Honey Farm in Josephine, northeast of Dallas. On this bright fall afternoon, the property is thick with bee magnets such as goldenrod, heath aster and other blooming wildflowers. In this part of southeastern Collin County, most owners of the 5- to 20-acre ranchettes keep their places mowed, making for fewer nectar targets for foraging bees.

In a spacious outbuilding stands a collection of stainless steel extractors that use centrifugal force to strip honey from the frames used in commercial hives. There are also massive tubs for storing the raw honey and an automated bottling machine. Scattered about are big blocks of beeswax, drums containing the most recent honey harvest and smaller extracting machines that Talbert uses to teach beekeeping classes.

“I have maybe $100,000 invested here, which is a lot less than the outlays you have to make for land and equipment in most parts of agriculture,” said Talbert, who has worked over the years through the Collin County Hobby Beekeepers Association to attract and educate new beekeepers.

But Talbert, a past president of the Texas Beekeepers Association, said beekeeping is in need of a youth movement. “If you look at the average age of beekeepers, they’re on my end of the spectrum, not Blake’s,” he said.

“It’s something the general public isn’t interested in. Today, it’s computers and such,” added Shook, president of the 300-member Collin County group that gave him his start.

Following the seasonal rhythm of the business, Shook ships his hives to Southern California for six weeks in the winter to pollinate almond crops. Hundreds of hives are stacked by forklift on a semitrailer, nets are put over the top, and the bees are sent where a broker has struck a deal between grower and apiarist, or beekeeper.

Shook also sends about half his hives to Houston, where the Chinese tallow tree, an otherwise loathed invasive species, provides a heavy flow of nectar that increases honey production in the critical late-spring and early summer months.

Parasitic mites that began invading hives in the 1990s and the recent, yet-to-be-explained Colony Collapse Disorder—in which honeybees leave the hive and don’t return—have challenged beekeepers like never before, and Shook has not been spared. He works to keep his bees healthy by feeding them pollen supplements and corn syrup in the winter, but he nevertheless expects to lose 20 to 30 percent of his hives each year.

There have been sufficient honeybees in Texas to pollinate the numerous commercial crops that need them—such as melons in the Rio Grande Valley and sunflowers, alfalfa and pumpkins in West Texas—according to Talbert.

But the shortages have raised honey prices and pollination fees, helping offset beekeepers’ rising costs.

Nathan Sheets, owner of the successful North Dallas Honey Co. in Plano, said buying local is becoming increasingly popular and fashionable. Sheets calls Shook “a great young man” and said the 20-year-old is likely to be helped by the trend.

Shook concedes Desert Creek Honey is by no means a big operation—yet. “It is simply a small business with big plans,” he said.

The Shook household is served by Fannin County Electric Cooperative.

Thomas Korosec wrote about fireworks in the July 2009 issue of Texas Co-op Power.