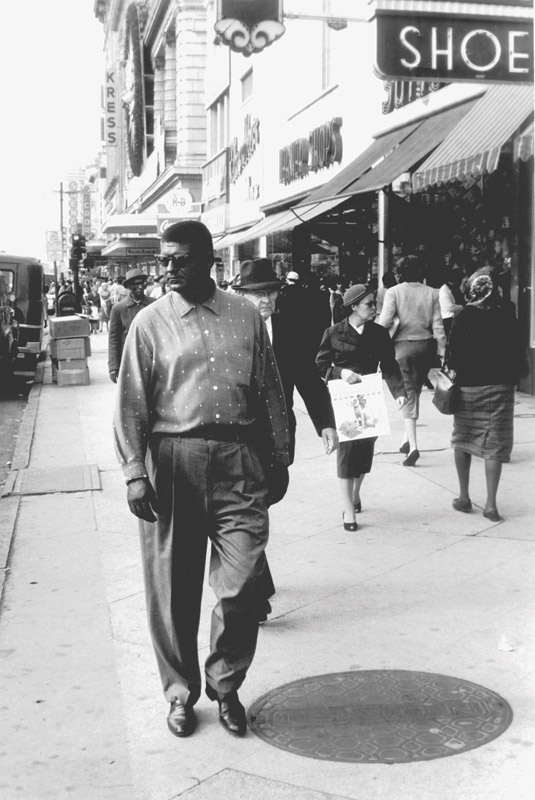

Without becoming a black man, author John Howard Griffin inquired in 1959, how could a white man hope to learn the truth about racial suppression? So, Griffin used medication to temporarily darken his skin and then traveled through the South as a black man for more than a month. His experiences formed the basis for Black Like Me, his 1960 book that has sold more than 10 million copies.

June 16 marks the 100th anniversary of Griffin’s birth in Dallas. He was educated in France and spent time in an abbey contemplating a religious vocation, then served in the U.S. military 1942–1945, suffering a shrapnel injury that caused him to lose his sight.

An exploding shell caused John Howard Griffin to go blind for a decade. During that time, he became a successful novelist.

Don Rutledge | Courtesy Wings Press

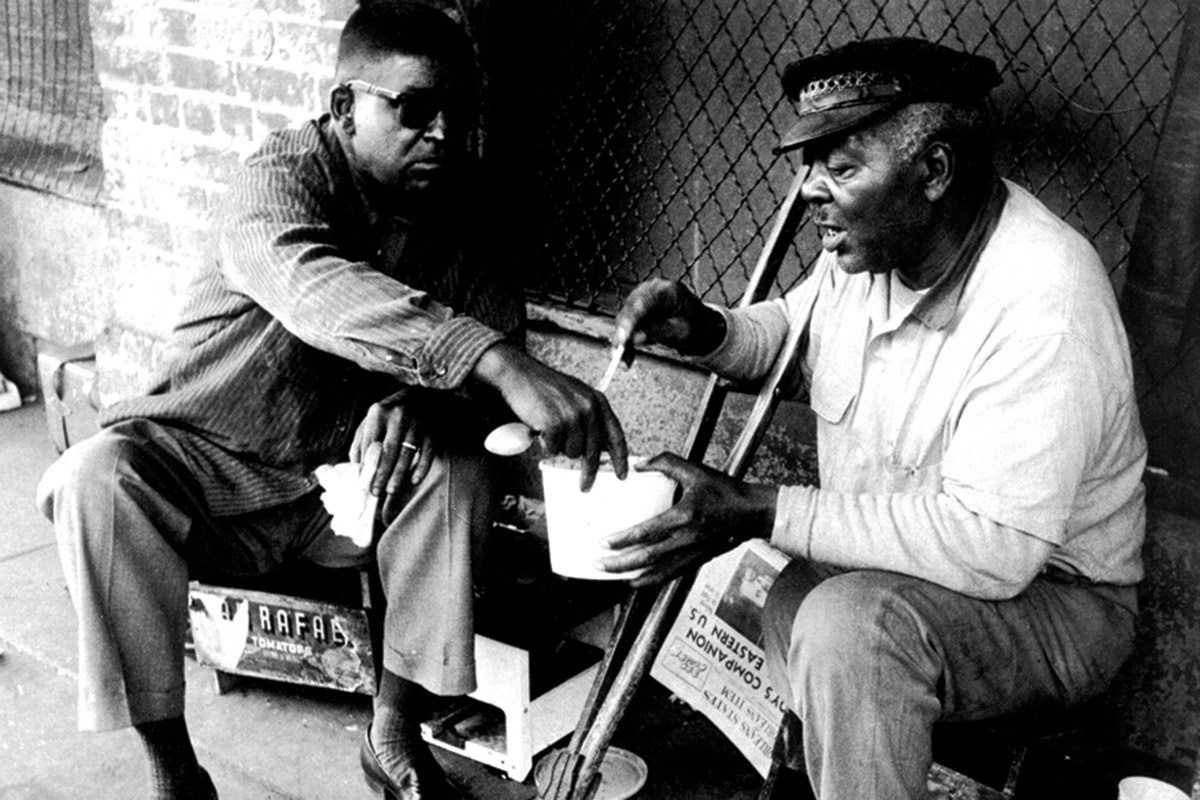

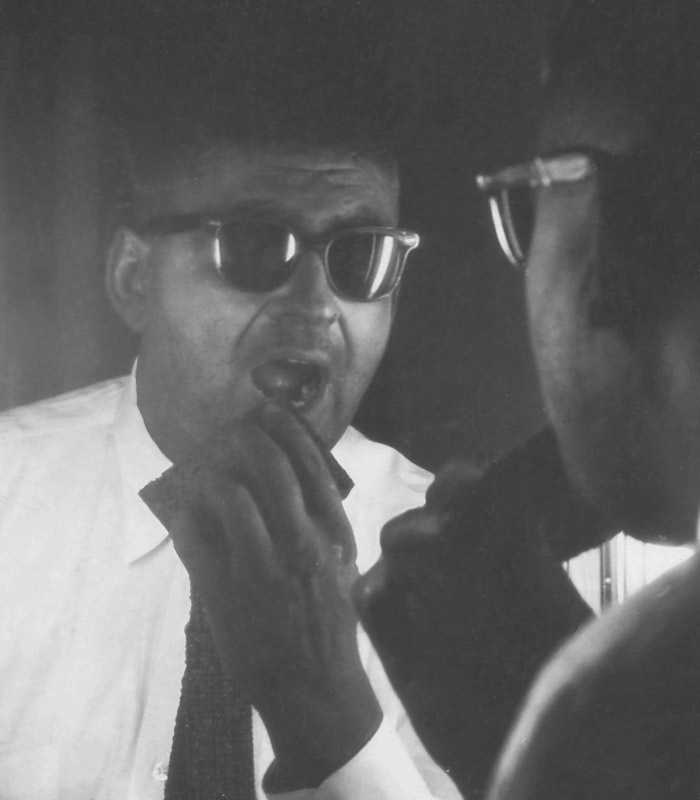

John Howard Griffin touches up the dye that darkened his skin and enabled him to travel the South as an African American.

Don Rutledge | Courtesy Wings Press

Griffin received death threats and was hanged in effigy in Texas, causing him to move his family to Mexico for nine months. He eventually cut back on his speaking, saying he found it absurd to presume to speak for black people when there were superlative black voices to do so.

Griffin developed diabetes and died in 1980 at age 60. His friend Robert Bonazzi, who later married Elizabeth, wrote several books based on Griffin’s journals. “He felt like he had an effect with his efforts, certainly back then,” Bonazzi says from his home in Austin. “Not too many white men would take on a black look and venture out into the world. It was brave and reckless, but he thought it was time for a white man to experience what a black man did, and there was only one way to do that.”

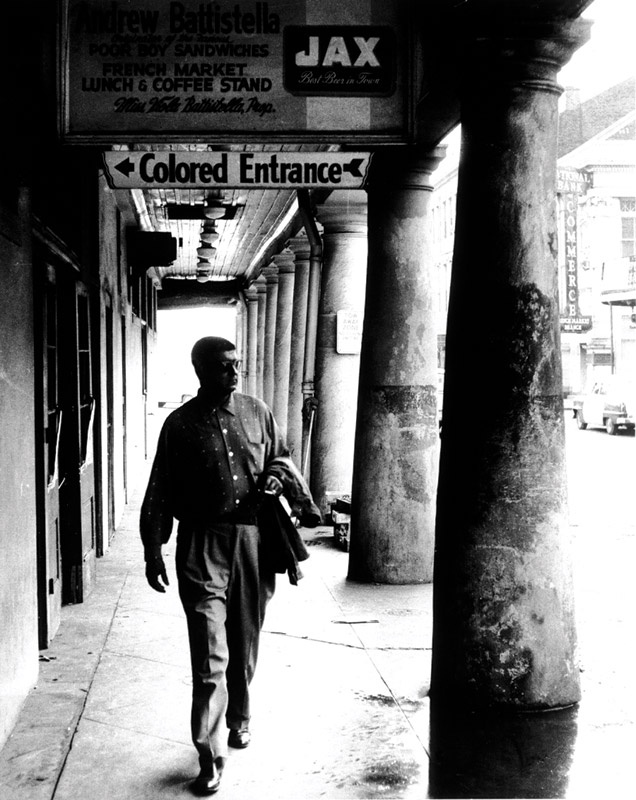

John Howard Griffin used a sunlamp to accelerate the process of darkening his skin so he could travel the South as an African American.

Don Rutledge | Courtesy Wings Press

Julie Hudson specializes in African American women’s literature at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin. “I think the book is important,” she says, “especially for a white audience, because it provides some insight into what it means to be black in America and into the issue of race and the implications of racism and hatred. There was so much anger in his community [in response to the book] because he was presenting the truth to people who didn’t want to face it, or didn’t care, or were embarrassed by it.”

Of course, she adds, Griffin always knew that he could return to his white life, which likely informed his writing. And while his family did have to flee, the furor died down and they were able to return home.

“The book still resonates today,” says Bonazzi. “He is much less known than he should be.”

Read more about Melissa Gaskill’s work at melissagaskill.blogspot.com.