Hans Boas was driving from California to his new life in Austin when he decided to stop for lunch in a picturesque Hill Country town.

Inside a German-style restaurant in Fredericksburg, he walked by a table of people who were speaking a language that was familiar to the German native. Well, sort of familiar.

“I heard these elderly gentlemen speaking this German dialect I had never heard before,” Boas recalls. Intrigued, he asked: “Where are you from?”

The men seemed puzzled by his question. “What do you mean?” they replied. “We’re from here!”

On his way to begin teaching Germanic linguistics at the University of Texas, Boas happened upon something he didn’t know existed: Texas German.

That chance encounter in July 2001 sparked a lasting passion and prompted him to establish the Texas German Dialect Project. Housed in UT’s Department of Germanic Studies and the Linguistics Research Center, the project’s mission includes recording and preserving the Texas German language as well as the culture and history associated with it.

“I just didn’t know about it,” Boas says. “Lots of people don’t know about it unless it’s your heritage.”

In Their Own Words

Listen to translated samples of Texas German as provided by the Texas German Dialect Project.

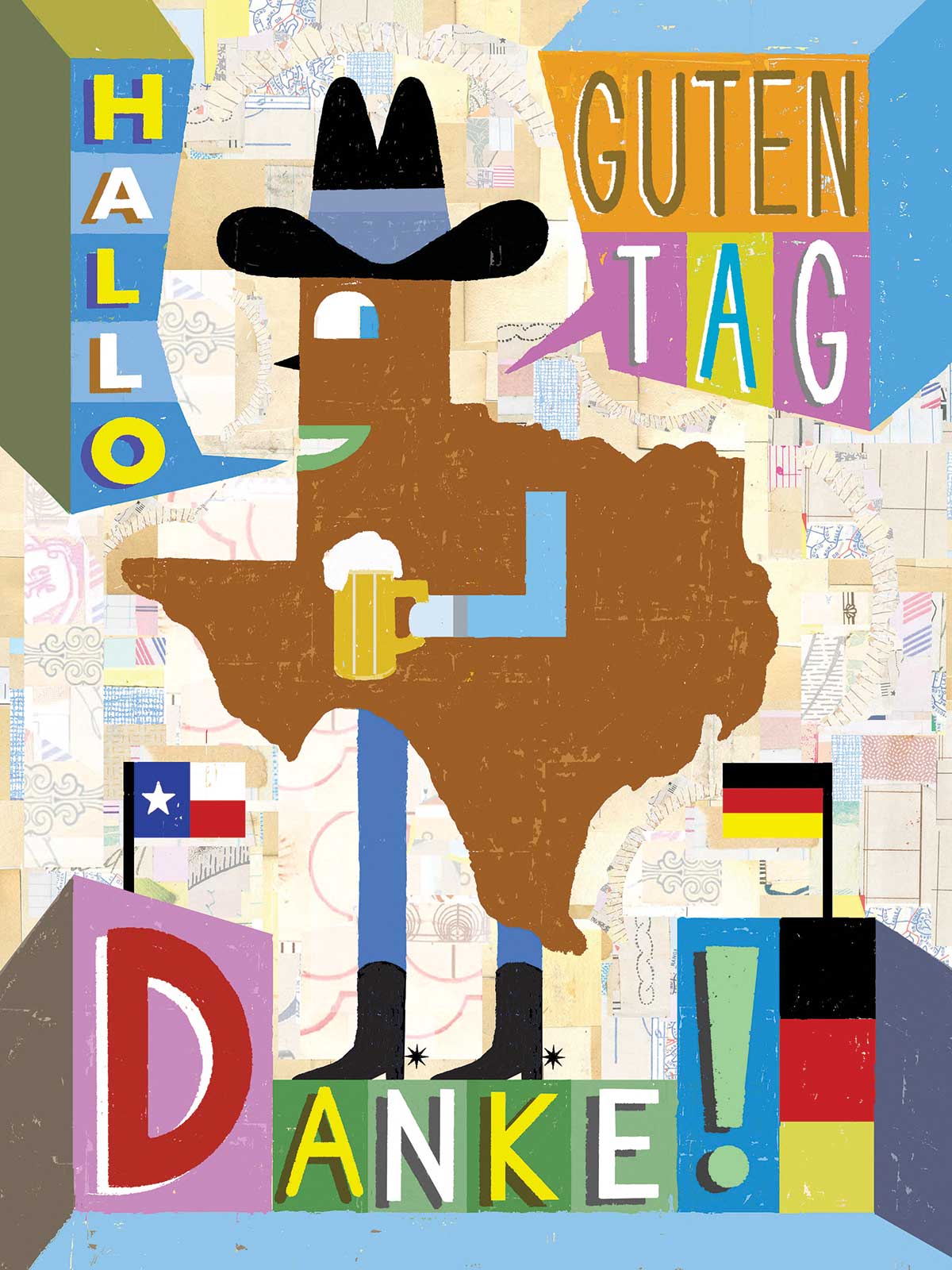

Texas German generally is spoken by people whose German ancestors first settled in Texas between about 1830 and the early 1900s. They came from various regions of Germany, speaking disparate dialects that melded into what became Texas German, though there are variations within the dialect. It differs from regular German in part because it hasn’t evolved much, as most languages do.

There were an estimated 160,000 speakers of Texas German around 1940, but that number has dwindled dramatically. The world wars fueled anti-German attitudes; laws were enacted that prohibited foreign languages in schools; and people moved from small communities to bigger cities.

Although there are no official numbers, Boas estimates that just 3,000–5,000 Texas German speakers remain. The dialect, he believes, will vanish in a decade or so—a void 200 years in the making.

“I think there is a certain sense of regret by some who would have liked to learn the language,” says Fredericksburg resident Evelyn Weinheimer, who grew up speaking Texas German. “It’s a missed opportunity for them.”

A primary objective of the project is interviewing Texas German speakers. Audio from those interviews is stored in the project’s Texas German Dialect Archive, which currently houses more than a thousand hours of interviews from more than 700 Texas German speakers.

“My idea was to enable students to get as close as possible to Texas German speakers—to hear spoken Texas German, to have that experience and not just be in the classroom,” says Boas, a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative.

Students interview Texas German speakers in the small communities where they live.

“It’s such a joy to be able to get away from your computer and go talk to somebody,” says Margo Blevins, a former project manager who has interviewed more than 100 Texas German speakers.

“It’s important to preserve it because it also is such a big part of Texas history,” Blevins says. “We’re trying to preserve the language but also the memories, the history and the stories.”

Weinheimer happily talked with Blevins. The 78-year-old retired teacher and part-time archivist lives in the same house where she grew up with the dialect. While she and her classmates were not allowed to speak German in school, “you would hear it up and down Main Street.” Her grandfather, she says, was offended if she didn’t speak German to him.

In 1977, after living in Austin for years, she and her family moved back to Fredericksburg, where she began to realize the dialect was dying. She believes the project’s work is invaluable.

“It is important to keep our culture and traditions alive with the language to share with the next generations,” says Weinheimer, a Central Texas Electric Cooperative member.

The search for Texas German continues, and the project recently received a sizable boost—a $1 million grant from an anonymous donor.

“The donation will help us interview as many speakers as possible in the next five years,” Boas says, “before Texas German will die out for good in about 2035.”