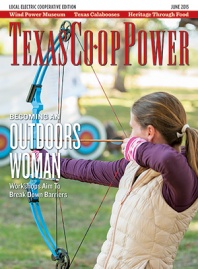

When you’re headed west out of San Antonio on Highway 90, the scenery changes almost immediately outside the city limits. Electronic billboards and fast food chains give way to fields dotted with oak trees. After the last convenience store, you’re more likely to see rustic gas stations and restaurants with names like Billy Bob’s Hamburgers. This transition from city into country seems fitting for me, a veritable city girl, as I drive toward Neal’s Lodges in Concan to attend one of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s “Becoming an Outdoors-Woman” workshops.

In terms of personal transformation, my expectations were low. I was under no illusion that this experience would magically change me into a modern-day Annie Oakley, especially given that the workshop lasted only about 48 hours. But the fact that I associated women and outdoors with a sharpshooting frontierswoman is ample evidence that I didn’t really understand why women across the state vie for a coveted spot on the BOW attendee roster year after year.

Over the next two days I learned a lot—not just about bicycle maintenance, firearms and fishing. I was reminded that there are scores of women who deeply enjoy outdoor activities traditionally populated by men. I also learned that, contrary to lingering cultural and gender stereotypes, these gals weren’t inclined to relinquish a drop of their femininity to do so.

BOW originated with a workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point in 1990. Conference collaborators identified 21 barriers that keep women from participating in hunting and angling. The barriers included things like how girls were reared and the intimidation women feel in all-male hunting or fishing groups. More than half of the barriers were rooted in education, meaning women didn’t know how to learn the skills or how to acquire the necessary equipment.

In an attempt to overcome those obstacles, Christine Thomas spearheaded the workshop that offers outdoor education classes in a safe, supportive, noncompetitive environment. About 100 women attended the 1991 event in Wisconsin, and it was so successful that other state agencies contacted Thomas to inquire about staging their own.

Today, BOW is offered in 39 states and in six Canadian provinces. The Texas chapter is run by the TPWD Hunter Education Program’s Heidi Rao, who took on the BOW coordinator role in addition to her full-time job as a hunter education specialist.

“BOW wouldn’t happen without other staff who believe in it just as much as I do,” she says. “They say, ‘If I don’t get paid to do this, I’m taking vacation, and I’m going to come do it anyway.’ Unbelievable.”

Believe it. All of the Texas BOW instructors are volunteers. Several are men, but Rao says they select mentors who are patient and enthusiastic about teaching women outdoor skills. Archery instructor Raymond Gonzales, who received rave reviews from the women in his classes, says he would actually rather teach women.

“They don’t have any preconceived notions on how to shoot a bow,” says Gonzales. “Therefore I’m able to teach them from the stance to the actual release of the arrow.”

The curriculum is divided into one-third hunting, one-third fishing and one-third “nonharvest” activities, which include camping, horseback riding and kayaking. Since I wanted to observe as many sessions as possible, the only class I actually participated in was bicycle maintenance, taught by TPWD biologist Brooke Shipley-Lozano. It was an empowering experience to learn how to repair and maintain my own bike, and it wasn’t as difficult as I thought it might be. The instructor’s insistence that I could do it fueled my determination, and I found that I wasn’t afraid to ask “dumb” questions because all of the other participants were learning for the first time, too.

Few of the women I interviewed grew up in a family or a community where they were encouraged to embrace outdoor activities that were considered masculine.

“That’s why this was created,” says Rao. “It was always the son or the grandson that got the gun; the girl got the doll. That’s just how most women were raised.”

That would explain why gender and cultural stereotypes still sometimes fuel the notion that women who hunt and fish are less feminine. To the contrary, many of the women I met at BOW seemed to be equally at home hitching a trailer as dancing in an impromptu Zumba class. Rao herself has four sons, is a professional hunting education specialist, and is a member of the National Rifle Association. But she also loves being a girl. She unapologetically confessed that she always puts on makeup—even when she’s camping.

Cosmetics and guns I could fathom. What I had a hard time envisioning was women who were enthusiastic about skinning animals. I was trying to keep an open mind about the “Oh Deer! Now What?” workshop, where students would “learn how to properly tag, field dress, skin, quarter and prepare game for transport.” To put it mildly, I’m not even remotely interested in the butchering process. And I wondered if any of the other women had actually signed up for it.

Sarah Padgett, a real estate agent from Midlothian, says her husband loves for her to hunt with him. But he made it clear that if she killed an animal, she would be dressing it herself. So she was the first to volunteer when the instructor asked who wanted to start the process. As Padgett enthusiastically began, both teacher and students offered her a steady stream of counsel and encouragement.

I found the same supportive, judgment-free learning environment in every session. Though I didn’t actually learn how to fly fish on this trip, watching Skipper Kessler demystify the art and technique of casting made me believe that I could. The way shotgun instructor Jimmie Caughron interacted with his students was reminiscent of an older brother taking his kid sister under his wing. And Steve Hall’s students were spellbound by his game-calling anecdotes and techniques.

By the end of the weekend, I wasn’t buying the use of “becoming” in the title. The women I encountered at Neal’s Ranch didn’t look like outdoor neophytes. Many were wearing badges and pins that marked them as “repeat offenders,” which meant that this wasn’t their first BOW event. But Rao says that doesn’t mean they’re proficient in all of the activities.

“We offer 30-something classes at this workshop, and attendees only get to pick four,” says Rao. “So they get here, they get their four sessions, and they go, ‘Oh my gosh! Look what they’re doing!’ and they want to come back. My rule is that if you come back, bring somebody to share this with you. Research shows that you’re more likely to continue an activity when you have a support system.”

——————–

Laura Jenkins is a writer and photojournalist based in Austin.