When Horton Foote’s first play, Wharton Dance, premiered in 1940, it not only named the young playwright’s hometown in the title—Foote used the real names of people he knew in Wharton.

“I didn’t have sense enough to know that you shouldn’t name real people in the play and have them do things that maybe their mother and father wouldn’t approve of,” he said in a 2006 interview with a Dallas radio station. “But I was trying to be truthful. I was told that was a great thing you should do as a writer. It taught me a great lesson because I meant no one any harm. I don’t use real names anymore, and I don’t use the name of my town anymore.”

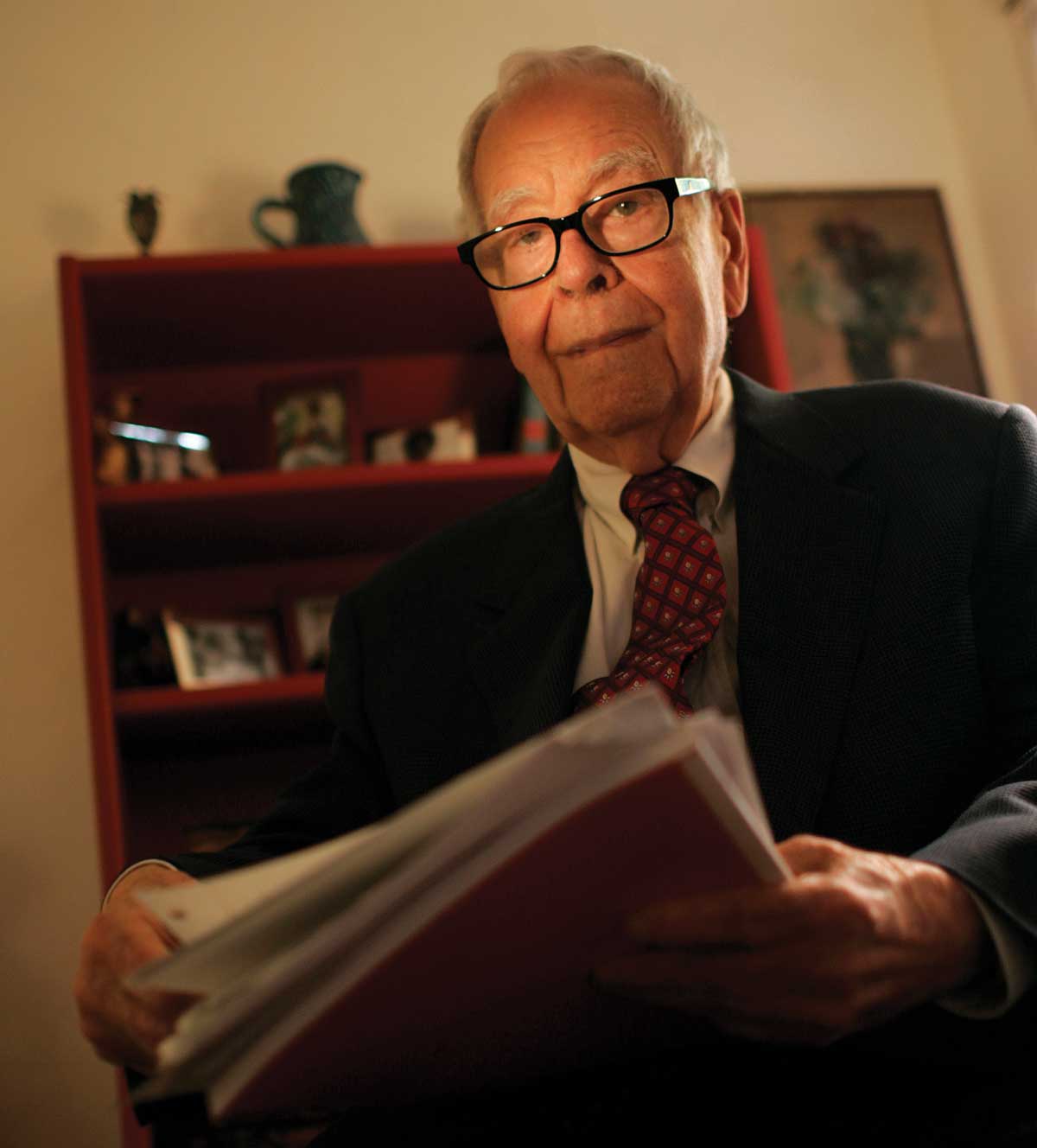

In a career that went on to span seven decades across the stage and screen, Foote conceded to fictional names, but the people and places that formed him remained at the center of his stories. In dozens of plays and screenplays, his sophisticated but simply told tales about the everyday drama of ordinary people earned him a Pulitzer Prize, two Academy Awards, the National Medal of Arts and myriad other accolades. They also put a spotlight on small-town Texas, where Foote set many of his most acclaimed works—including The Trip to Bountiful, about an older woman’s quest to return to her childhood home one last time, and Tender Mercies, about a middle-aged, down-on-his-luck country singer.

To find inspiration for his stories, Foote didn’t have to travel far outside Wharton, about 60 miles southwest of Houston on the Colorado River, but his journey to becoming a writer took him much farther.

Foote left Wharton at 16 with hopes of becoming an actor. He attended acting school in Dallas and after a year moved to California to study at the Pasadena Playhouse before heading to the epicenter of theater, New York City. There he met choreographer Agnes de Mille, who encouraged Foote to try his hand at writing.

In his second memoir, Beginnings, published in 2001, Foote recalls the conversation that would prove to be a turning point in his career: “When Agnes suggested I write a play, I asked, ‘What shall I write about?’ … ‘Write about what you know,’ she said.”

After Wharton Dance came a three-act play titled Texas Town, which Foote wrote in his parents’ house in 1941 during a five-week visit home from New York. Like many of his plays that followed, Texas Town paints a vivid portrait of a small community, this one populated by youngsters and old-timers who gather and gossip at the local drugstore.

While Wharton and its people held a special place in Foote’s heart, he was enamored of many of Texas’ small towns. In Farewell, he writes: “One of the pleasures of making films of mine that were set in Texas was riding around with the director and art director, looking for towns that might help establish a sense of late-19th-century and early-20th-century Texas, towns like Waxahachie, Palmer and Ennis.”

One of his favorite locales was the northeast Texas town of Venus, which was used for two of his films: On Valentine’s Day and 1918.

Even though Texas was a common setting for Foote’s plays, and he came to be known as “the Chekhov of the small town,” his subjects transcended time and place. Themes such as love and loss, disappointment and regret, and hope and new beginnings filled his works.

“Horton was the great American voice,” Robert Duvall told The New York Times. The actor, who made his screen debut in To Kill a Mockingbird (for which Foote won an Oscar for best adapted screenplay) and later starred in Tender Mercies, added: “His work was native to his own region, but it was also universal.”

Just as Foote carried Wharton with him, the town carries the playwright’s memory today. At the Wharton County Historical Museum, visitors can view Foote memorabilia. And the Plaza Theatre, which presented Foote’s play A Coffin in Egypt in April, calls its performers the Footeliters.

“Horton Foote has been a very influential member of our community,” says Sarah Wilkins, board member at the Plaza Theatre, which got its start as a theater guild Foote helped found in 1932.

Wilkins can attest to his influence of the townspeople of Foote’s time. “His children were playmates of my parents,” the Wharton native says, “and he … was a friend to both sets of my grandparents.”

Though Foote was in Connecticut at the time of his passing, he was buried in his beloved Wharton. His gravesite lies just blocks from the house where he grew up, the house he returned to throughout his nine decades and the house that stands as a reminder of countless stories well told.