With one hand, Wimberley artist Michael Ford grips what looks like a glossy beige birdhouse shaped like an hourglass and etched with black tendrils. Then he gives it a shake. Boom, boom—BOOM. The deep rumbles startle passersby at the Lone Star Gourd Festival in Fredericksburg. Like me, they’re dumbfounded.

“This is a thunder gourd,” says Ford, a Pedernales Electric Cooperative member. When shaken, a spring vibrates a drumhead, creating ominous notes that emanate through holes in the gourd.

“It’s very functional. If your company stays too long, just duck into a hallway with your gourd,” Ford says, grinning, then shakes it again, setting off more thunderous booms. “Then tell your guests, ‘Uh-oh, storm’s coming. Better leave while you can!’ ”

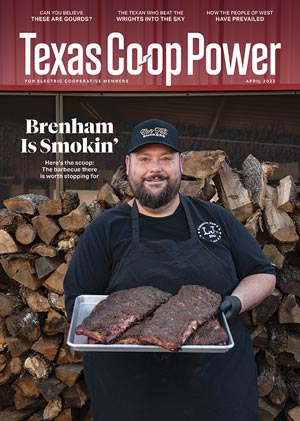

Ford’s joking, of course. But he’s dead serious about the art form that he calls his passion—much like his fellow gourd artists all over Texas. Using an array of techniques, they create bowls, holiday décor, birdhouses, masks, sculptures, jewelry, lamps and miniature hobbit homes, to name a few examples. There are simple designs, like painted gourds, and richly embellished pieces that can sell for thousands of dollars.

Michael Ford’s pieces sometimes incorporate multiple gourds.

Julia Robinson

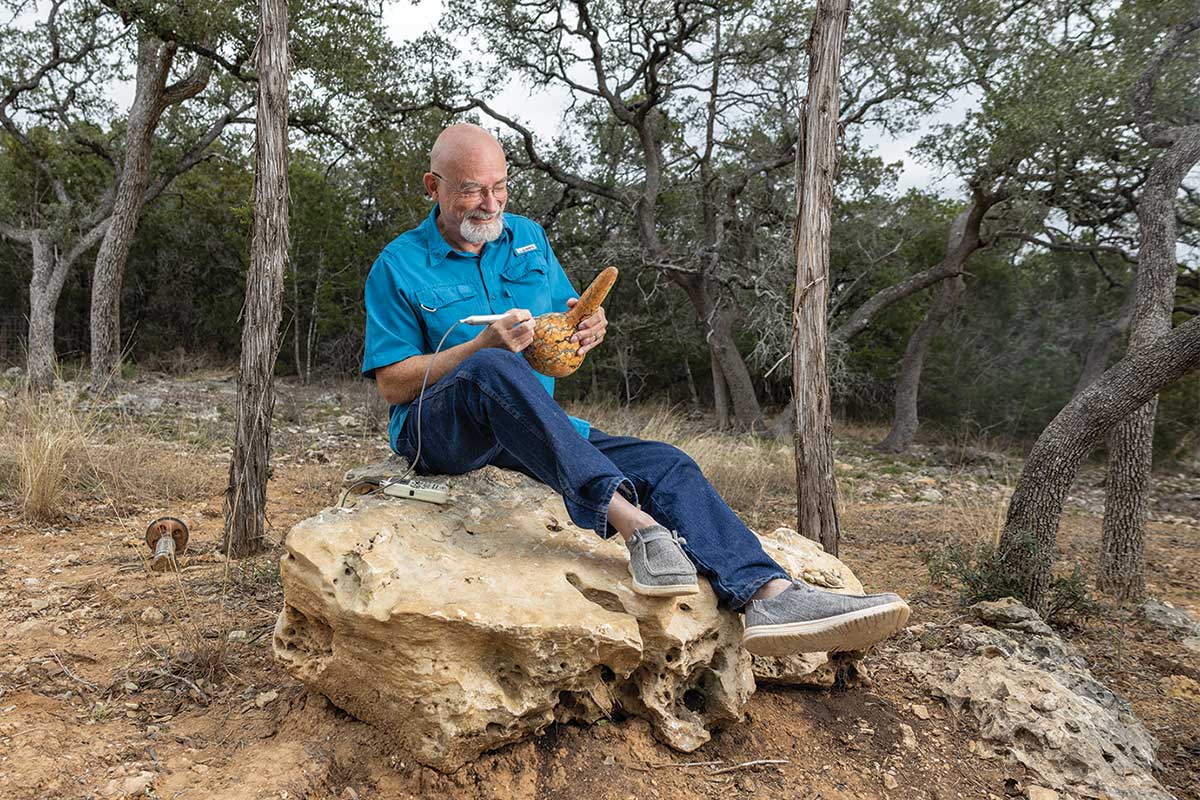

Ford, a former graphic artist for the Texas Department of Transportation, has been turning gourds into art since 2013.

Julia Robinson

But wait—what is a gourd? Is it just a smooth pumpkin? Well, close. Gourds and pumpkins, along with squash, melons and cucumbers, are members of Cucurbitaceae, a plant family that produces hard-shelled fruits that humans have used for food, ornaments and utensils over thousands of years. Experts believe gourds are the only plants that have been grown around the world since prehistoric days.

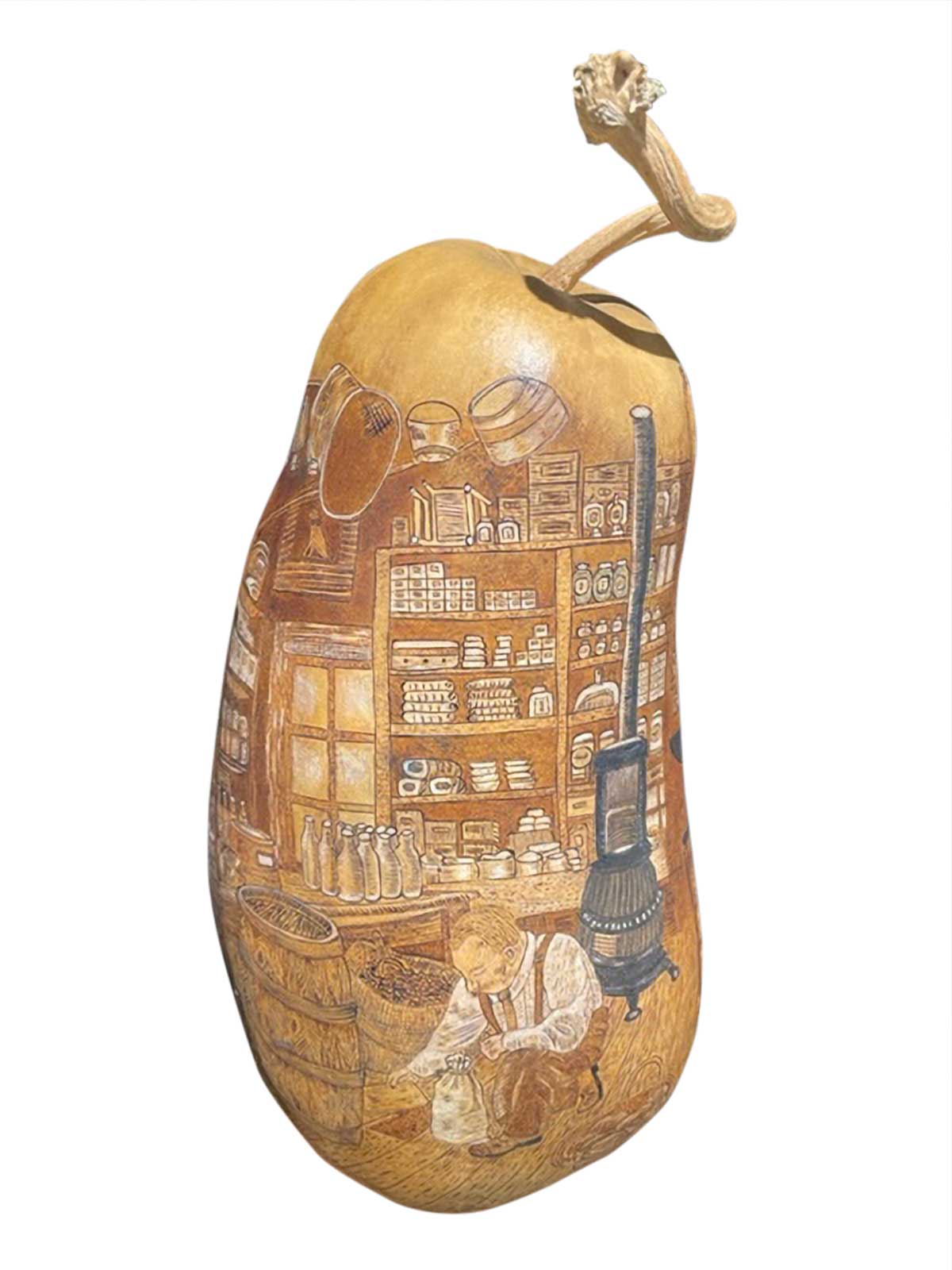

Historians in Peru have unearthed ancient gourd fragments associated with early humans. For generations, Peruvian artist Ana Poma and her neighbors in Cochas Chico have passed down the tradition of carving and burning intricate designs onto gourds as a way of storytelling. “Families teach their children,” says Poma, a vendor and teacher at the Fredericksburg festival. “I learned as a child from my mother, uncles and grandparents.”

For some artists, though, not just any gourd will do. Forget using our thin-skinned Texas natives, such as buffalo and balsam gourds. Instead, many artists prefer hard-shelled and decorative gourds available in endless shapes, sizes and thicknesses. Thicker shells (three-eighths of an inch thick or more) are sturdier for carving and burning. Standard gourd shapes, designated by the American Gourd Society, include cannonball, basketball, martin house, dipper, club and banana.

Many artists order their gourds from professional growers, such as the Wuertz Gourd Farm in Arizona and the Welburn Gourd Farm in Southern California. Some grow their own. John and Rickie Newell, Central Texas EC members near Llano, grow gourds. At the festival, Rickie—an artist who displays her work at the Llano Art Guild and Gallery—has a bin piled high with gourds for sale, ranging from 50 cents to $12. Typically, gourds are priced according to their widest diameter. Those that have been cleaned on the outside and/or had their seeds and pulp scraped out cost more.

“We plant our gourds around April 15,” Rickie says. “Then we harvest when they’re dead in the field from October up to Christmas and dry them in a metal cage.”

Choosing a gourd is just the first step for many artists, and gourd shows are an ideal place to learn about the craft and expand skill sets. This Texas show is one of a handful of annual events held across the U.S. that attract hobbyists and professionals alike. Artists and vendors welcome questions, and many sell basic supplies. The Texas Gourd Society, the nonprofit organization that sponsors and organizes the annual Lone Star Gourd Festival at the Gillespie County Fairgrounds, is also a resource for crafters. Across Texas, the society has regional chapters called “patches.”

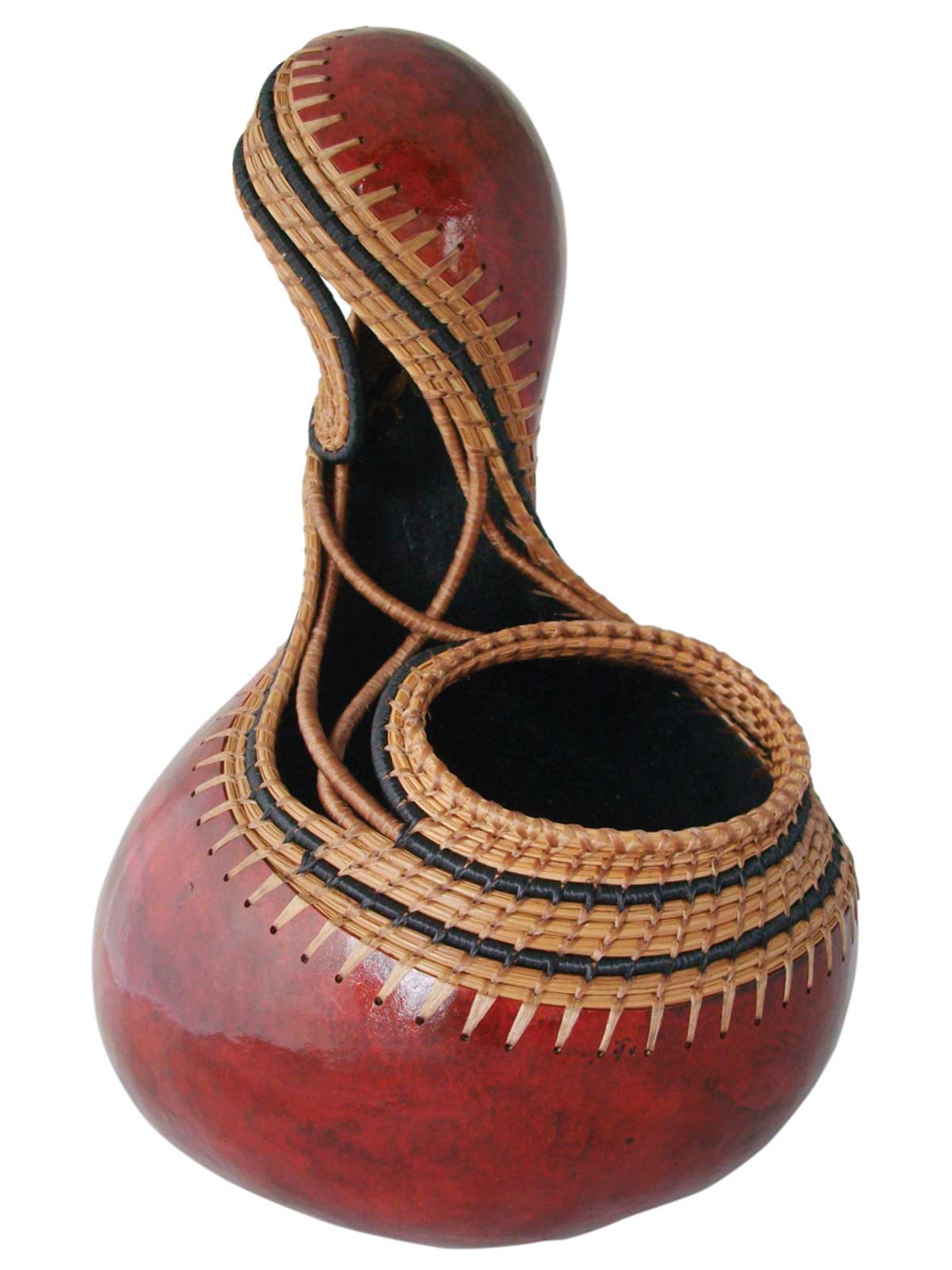

Standing Tall by Roy Cavarretta.

Courtesy Roy Cavarretta

Chasing Dreams by Jill Robinson

Courtesy Jill Robinson

“We learn techniques from each other, like leather stitching,” says Sherry Nelson, a member of the Guadalupe Gourd Patch in Kerrville. “In the gourding world, though, you never copy someone’s work. Instead, you can use their technique as an inspiration to create something new.”

On her gourds, Nelson, a Central Texas EC member, uses various methods, such as burning; carving; painting; applying alcohol dyes; and attaching horns, beads and cactus fibers. “Pyrography is my favorite,” she says. “I can draw with my wood burner for hours. It’s very relaxing.”

Like many gourd artists, Roy and Blanche Cavarretta, who live in Hallettsville and are members of San Bernard EC, started out by growing gourds and turning them into birdhouses. Then, while traveling in New Mexico, they viewed a gourd art exhibit at an art festival. “We had no idea so many things could be done with them,” Roy recalls. “It set us on a journey we never could have imagined. There’s not a day goes by that we’re not working on a gourd.”

That was 11 years ago. The Cavarrettas still grow gourds. They’ve also become master gourd artists who’ve won countless awards. “At art shows, you enter at the novice level,” Roy explains. “When you win at that level, you advance to intermediate, then advanced and master.”

A James Medders spiraling piece.

Courtesy James Medders

Together, the couple market their work as Gravel Road Arts. On her urn-style gourds, Blanche primarily uses pyrography, transparent dyes and a weaving stitch called closed coiling. Flowers, hummingbirds, dragonflies and inlaid gemstones adorn many of her pieces. Similarly, Roy uses pyrography and dyes along with chip carving using a gouge. His designs lean toward contemporary and Southwestern themes, such as his Spirit Doll that won Best of Show at the Fredericksburg festival.

The People’s Choice award went to Chasing Dreams, a large kettle gourd intricately crafted by Austin’s Jill Robinson. “I use a lot of random techniques,” she says of her striking designs. “On this one, I used enameling, woodburning, stipple carving and alcohol inks along with real cactus fibers and carved cactus fibers.”

Visit with Robinson and other gourd artists, and you’ll quickly pick up on their camaraderie and deep love for the craft. When artist James Medders of Morgan Mill lost the use of his left hand, Roy Cavarretta rigged a carving vise that could hold a gourd in place for his friend. Soon Medders, a United Cooperative Services member, was back to woodburning, carving and painting on his gourds. Using a method called pine needle coiling, he also stitches longleaf pine needles into elaborate designs.

“Once I got started in gourd art eight years ago, I had a passion,” says Medders, who has also won awards. “Why? I don’t know. I just do. Sometimes my wife tells me, ‘Put that gourd down! We’ve got somewhere to go.’ ”

Rickie Newell continues work on her angel with wings.

Julia Robinson

Meanwhile, across the exhibit hall at the festival, a hands-on art area called the Imagination Station beckons newbies of any age. From a big pile of gourds, I choose a little one cut open like a bowl. Then I plunk down at a table with metallic paints, rhinestones, a paintbrush and a sponge.

“One of our goals is to pass on gourd art to young people so it won’t die out,” says Rona Thornton of Austin, who’s overseeing the area. “I take the Imagination Station to garden clubs, schools and military bases. It’s fun to see people who think they’re not artistic create their own piece.”

That would be me—I’m definitely no artist. But wait! Before long, my plain gourd has transformed into a sparkly urn. Wow, I am an artist.

Thornton smiles. “Anything’s possible with a gourd,” she says.

Artist: Jill Robinson

Green Goddess by Jill Robinson

Courtesy Jill Robinson

Artists: The Cavarrettas

Blanche and Roy Cavarretta’s hobby has them “on a journey we never could have imagined.”

Julia Robinson

Blanche Cavarretta uses a drill to create a stipple pattern.

Julia Robinson

Drill bits that the Cavarrettas use to shape and embellish their gourds.

Julia Robinson

Roy Cavarretta gathers pine needles into coils to finish a piece.

Julia Robinson

Blanche Cavarretta uses waxed thread to create coils atop a gourd.

Julia Robinson

Above left: Hearts of Stone by Roy Cavarretta won people’s choice at the 2016 Southwest Gourd & Fiber Fine Art Show and first place in the masters division at the 2016 Lone Star Gourd Festival. Above right: The Iris Dance by Blanche Cavarretta won best in class at the 2020 Ruidoso Art Festival.

Hearts of Stone Courtesy Roy Cavarretta. The Iris Dance: Courtesy Blanche Cavarretta

The Cavarrettas’ gourd patch.

Courtesy Blanche and Roy Cavarretta

Artist: Michael Ford

Michael Ford first tried gourd art in 2013 and started winning awards for his sculptural pieces.

Julia Robinson

Pyrography creates veining in the skin of the gourd that Ford has inlaid with turquoise.

Julia Robinson

Ford carves tiny homes out of several gourds. Some of the homes have removable roofs and tiny furniture inside. One gourd provides the roof and another the small house.

Julia Robinson

Artist: Sherry Nelson

Sherry Nelson used an illustration from a Texas Co-op Power story to create her prizewinning work.

Courtesy Sherry Nelson

Artist: Rickie Newell

Rickie Newell started growing gourds for birdhouses in her garden in Llano in 2010. She hosts monthly meetings of gourd artists to socialize and create art on her front porch.

Julia Robinson

Newell stores gourds from her garden and others collected from friends or bought in Arizona in a storage container to keep them dry until she’s ready to work on them.

Julia Robinson

Newell uses a drill to create a relief design in a gourd.

Julia Robinson