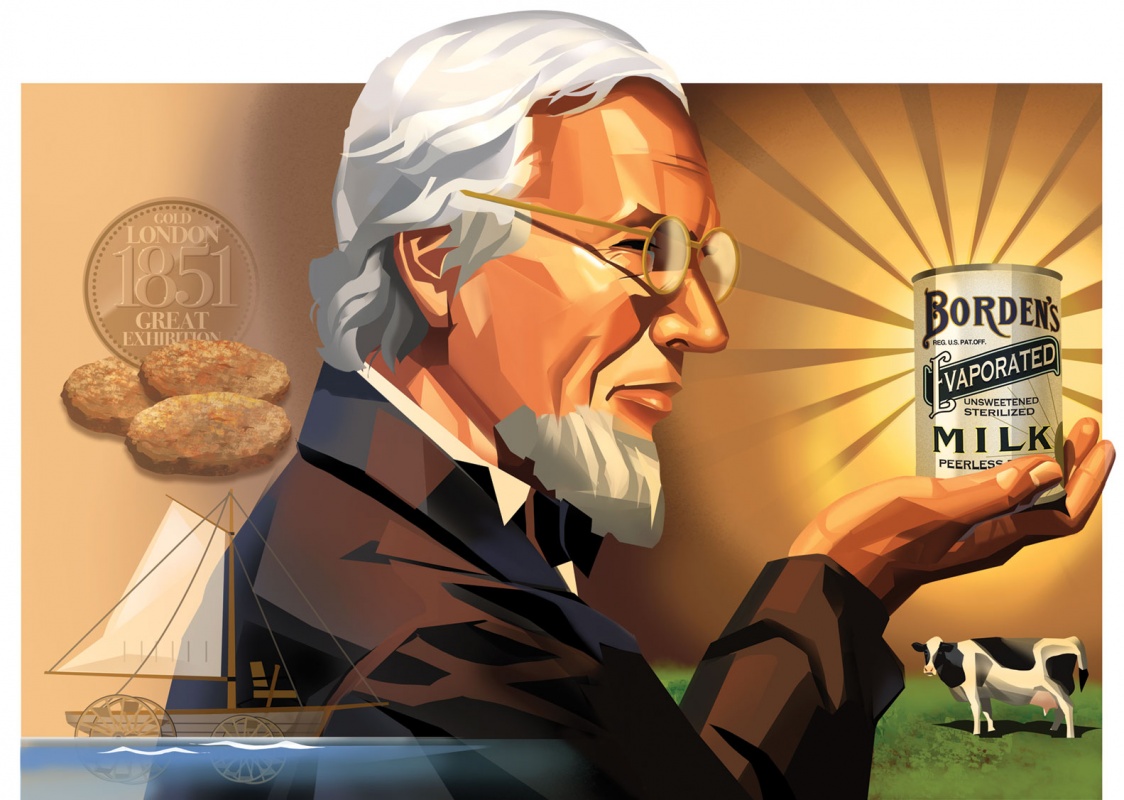

Gail Borden Jr., an inveterate inventor with just a year and a half of formal schooling and not a scintilla of scientific training, discovered an ingenious method of condensing milk so it could be stored without refrigeration and safely shipped great distances. The 1856 invention reversed the dismal failure of his earlier discoveries.

In 1844, when he lived in Galveston, Borden lost his wife and 4-year-old son to yellow fever. Devastated, he reasoned that, because the disease raged in summer and receded after the first frost, a giant refrigerator could “keep patients for a week under a white frost” and cure them. No one volunteered to test the theory.

Another invention, a terraqueous machine, was supposed to navigate land and sea equally well. The wagon-sailboat combination, complete with mast, sail and wheels that served as paddles in the water, worked admirably when a horse pulled it across land. However, on its first voyage into the Gulf of Mexico, the contraption capsized and dumped its passengers into the surf.

Despite these spectacular failures, Borden was not a buffoon. Born in 1801 in Norwich, New York, he was a teacher and surveyor and was said to have been captain of the local militia before his move to Galveston. In Texas, he founded a newspaper, The Telegraph and Texas Register, and prepared the first topographical map of the state.

In 1849, a Borden invention called meat biscuits promised wholesome, portable nutrition, and the biscuits won a gold medal at London’s Great Exhibition in 1851. Borden explained that the nutritive portions of beef or another meat would be separated from the bones and other parts of the body by boiling. Next, the water holding the nutritious matters in solution would first be evaporated to extreme thickness and then made into a dough with firm wheat flour. This meaty dough would be rolled and cut into a biscuit shape, then baked at a moderate heat to achieve the appearance and firmness of crackers—so it would keep for years.

The chairman of jurors at the Great Exhibition called it “one of the most important discoveries of the age.” Borden set up a plant in Galveston to manufacture meat biscuits for a worldwide market.

Borden planned to market them with a partner named Ashbel Smith.

“Dr. Smith, a gentleman of scientific reputation,” according to an 1850 article in Scientific American, “has communicated a paper on the subject to Prof. Bache, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science,” in which he says, “I have several times eaten of the soup made of this meat biscuit. It has a fresh, lively, clean and thoroughly done or cooked flavor.”

In spite of favorable recommendations from Smith; Texas Ranger Rip Ford, who preferred to sweeten and fry the biscuits; and Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, who took a supply on two Arctic expeditions, the meat biscuit failed to win badly needed military contracts.

The Army deemed it “not only unpalatable, but [it] failed to appease the cravings of hunger, producing headache, nausea and great muscular depression.” By 1852, Borden, who had poured his fortune into the manufacture of meat biscuits, was bankrupt.

Just three years later, in 1855, he employed an oddly shaped copper vacuum pan to successfully condense milk. The dairy business boomed. Borden’s Eagle Brand Condensed Milk saw many a starving soldier through the Civil War and escorted Gail Borden’s bank balance back into the black.

Martha Deeringer, a member of Heart of Texas EC, lives near McGregor.