It happened around dusk one evening in 2001 or 2002. Judi Johnson can’t recall the exact year, but she’ll never forget what she saw while heading home along CR 777, just south of the Jasper County community of Curtis. Johnson screeched her white Mercury Sable to a dead stop in the middle of the narrow, deserted lane.

Suddenly, she found herself eye to eye with a tawny-gray mountain lion. Spotlighted by the car’s headlights, the creature paused for what seemed an eternity. “I looked at him, and he looked at me,” said Johnson, a Jasper-Newton Electric Cooperative member. “He appeared to take up the whole road. I could see the muscles of his body, that’s how close I was. It was like he was waiting on me to make the first move. Then, in the blink of an eye, he sprang into the dense, darkening East Texas woods. It was the most beautiful animal I’ve ever seen!”

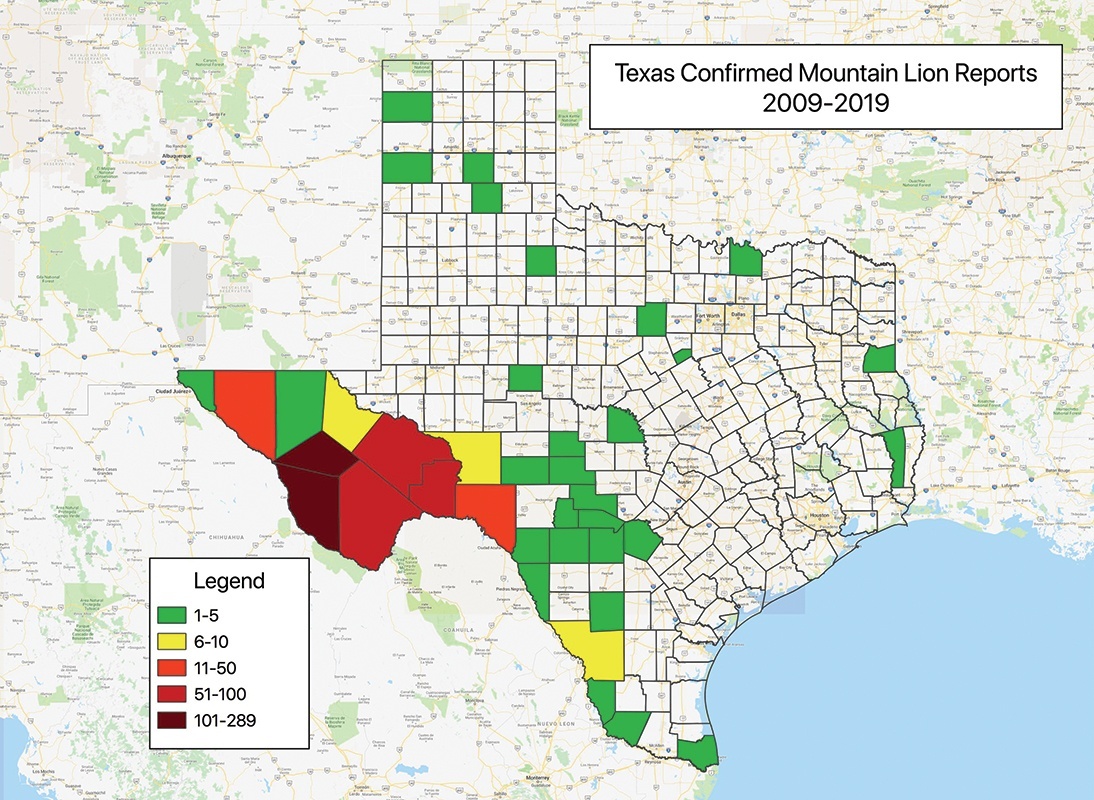

There have been just three confirmed sightings of mountain lions in the eastern half of Texas in the past decade, according to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

For decades, wildlife biologists, conservationists and hunters have tried to document East Texas sightings of animals that were once common here but were hunted to near extinction a century or more ago—species such as mountain lions (also called cougars, panthers or pumas), black bears and wild turkeys.

Wild turkeys have made somewhat of a comeback, but sightings of mountain lions and black bears remain extremely rare. A solitary soul may occasionally traipse through East Texas—especially in wild, isolated territory such as the Neches River bottom where Johnson had her encounter.

The state agency that tracks these sorts of things, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, reports that mountain lion sightings have occurred in all of the state’s 254 counties. In fact, before Anglo settlement of Texas began in the 19th century, breeding populations of cougars lived throughout the state. Heavy hunting around 1900 killed an estimated 100,000 mountain lions. Once the most widely distributed cat in the Americas, it’s now only common in Texas in the mountainous Trans-Pecos region and the deep Rio Grande Valley.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

Just three confirmed sightings of mountain lions have occurred in the eastern half of Texas in the past decade, according to Jonah Evans, TPWD’s state mammalogist. Game cameras photographed cougars in 2010 in Panola County, in 2011 in Jasper County and in 2018 in Grayson County.

“There’s no way to know where they came from,” he said, adding that the stealthy felines could have trekked hundreds of miles from West Texas or far South Texas and hardly been detected.

Generations of folks living in the Pineywoods have talked around kitchen tables and local cafes about “black panthers” roaming the forests.

“We get calls almost every week about black panthers,” notes Livingston-based TPWD biologist Chris Gregory. “There has never been a confirmed black panther sighting here or anywhere. If they were out there, we’d probably have one on a game camera somewhere. Many of these reports may be large bobcats, which can be melanistic (all black). There was one killed in this area in 2016. But myths about panthers are hard to put down because folks get convinced of what they saw.”

Turkey Time

It was broad public support—especially among hunters—that brought success to a decades-long quest to repopulate Texas and the nation with wild turkeys. Habitat destruction and unregulated hunting nearly eradicated wild turkeys from the U.S. by 1900. In the 1930s, the federal government put a tax on sporting goods and ammunition to pay for large-scale wildlife restoration projects. It took decades, but the national turkey population more than quadrupled to 1.4 million birds by the 1970s.

Turkeys now inhabit 223 of Texas’ 254 counties. The state launched its own restocking program decades ago to repopulate the Rio Grande wild turkey, mainly west of the Trinity River. It proved wildly successful, according to Jason Hardin, TPWD upland game bird program specialist.

Along with the program’s ongoing success, recent years of ample and timely rainfall have helped turkeys rebound from earlier periods of drought, Hardin adds. In good years, the Rio Grande turkey population can top a half-million, according to TPWD reports.

The runaway success of Rio Grande turkeys has not been duplicated in the restocking program of eastern wild turkey in East Texas, Hardin notes.

“The natural environment in eastern counties is very different from the Rio Grande turkey habitat,” he says. “East Texas has lots of rain resulting in heavy undergrowth, which is not the ideal turkey habitat, plus it also encourages predators. Eastern wild turkeys need open grassland mixed with woods, so we need prescribed burns to maintain an open understory.”

During the past decade or so, TPWD has paid more attention to the kind of habitat that turkeys like in the Pineywoods. “We used to do ‘block stocking’ by putting 15–20 birds per site over five to 10 sites per county,” Hardin says. “That was not as successful as we wanted.”

Restocking larger populations seems to allow turkeys to better survive changes in environment and natural attrition.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

These days, TPWD—plus partners at universities and the National Wild Turkey Federation—focuses on “super stocking” in prime habitat. That involves the restocking of 80 birds per site where habitat meets optimal conditions.

“We need at least 10,000 contiguous acres of mixed forest and grassland, even if it involves more than one landowner. We want genetic flow across landscapes, not just islands of birds,” Hardin explains, adding that the watersheds of the Neches River, Sulphur River and Cypress Creek remain target areas.

Restocked birds are captured in other states using cannon nets and brought to Texas for mass release. Many are GPS-tagged so biologists can track their movements. Restocking larger populations seems to allow turkeys to better survive changes in environment and natural attrition.

“Monitoring success is always difficult, but harvest numbers are key to knowing what’s happening on the ground,” Hardin says.

To that end, he adds, hunters must report turkey harvests online or through a phone app within 24 hours of a kill. “If we don’t see good harvest numbers, we assume the population is in decline and might close a season. Only time will tell how successful we are. If more East Texas counties get hunting seasons in coming years, you’ll know it’s been a success.”

Bearly in East Texas

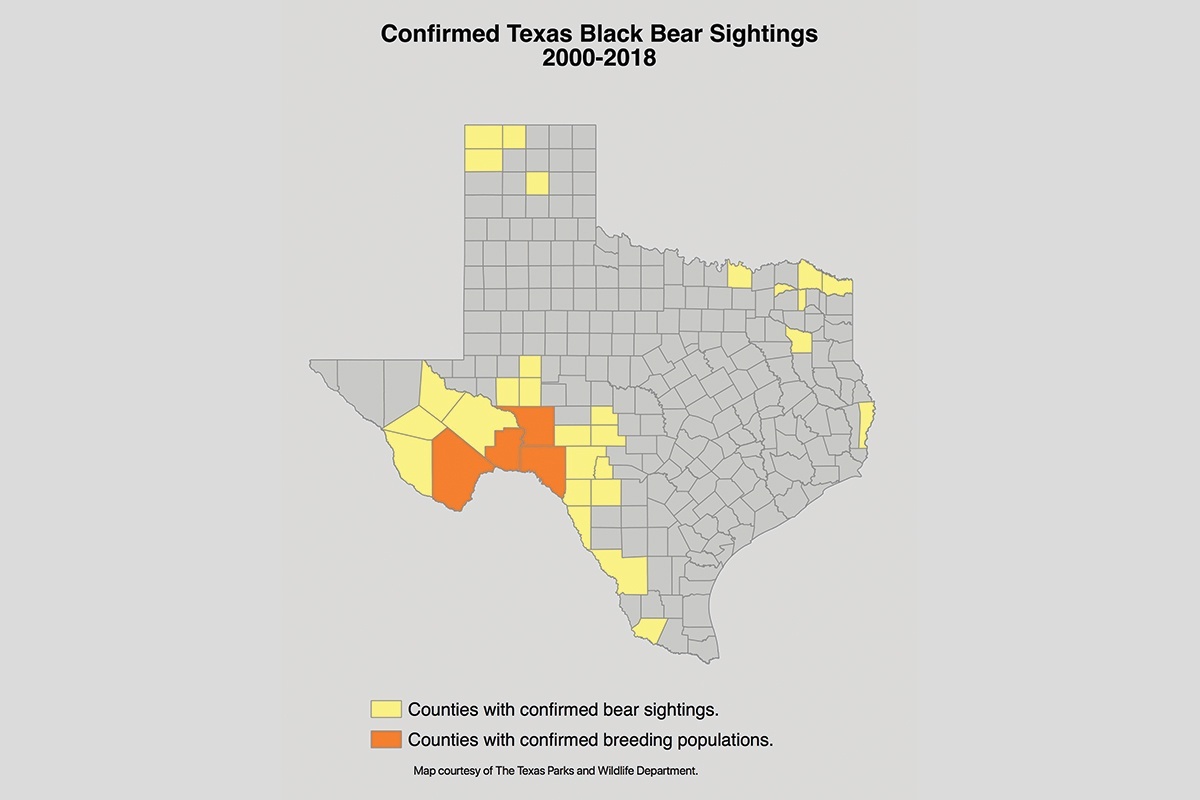

Reports of bear sightings abound from the Red River to the Gulf Coast, but evidence is hard to come by. Media headlines—such as “Black bears returning to East Texas”—exaggerate claims beyond what science can verify.

The gold standard of species identification is the Class 1 sighting, says Dave Holdermann, TPWD nongame wildlife biologist for the eastern half of Texas. “We don’t place much stock in reports that do not include definitive evidence, such as game cameras or other photos, track prints or hair samples that our biologists can verify,” he explains. “Many black bear sightings are probably black wild hogs that have a profile in the woods very similar to black bears.”

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

Holdermann and mammalogist Evans are now reviewing older, pre-2000 Class 1 black bear sightings, some of which lack supporting evidence. The most up-to-date Class 1 report shows 34 black bear sightings in East Texas since 2000. Recent sightings include seven in 2016 from Red River, Bowie and Smith counties and none in 2017. Five reports in 2018 came from Cass, Fannin, Delta and Grayson counties. These are all counties in northeastern Texas, not far from the Red River. The last southeastern Texas sighting came in 2009 from a game camera in Newton County, though TPWD has not fully vetted that report. Same-year sightings could be the same bears showing up in different locations, as they are not tagged, explains Holdermann.

Black bear activity in East Texas appears to follow a pattern. “The pattern is that we don’t have a resident breeding population of black bears in East Texas, but we do see a few mainly young male bears dispersing from breeding populations in adjacent states,” Holdermann said.

Wildlife scientists estimate approximately 5,000 black bears live in the southern Ozark and Ouachita Mountains in southeastern Oklahoma and southern Arkansas. That breeding population seems to be increasing, which causes some bears to wander into northeastern Texas.

“Female bears tolerate female offspring but not the males. So young males come into our area looking for reproductively active females or perhaps food,” Holdermann notes. “They find good habitat but no other bears, so they go back where they came from.”

This image of a black bear was captured in 2007. Young male bears may wander away from populations in Louisiana into East Texas.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

A similar pattern could happen in southeast Texas with young males wandering away from active breeding populations in Louisiana, says Adrian Van Dellem, president of the Woodville-based Texas Black Bear Alliance. The nonprofit conservation group educates the public about black bears to promote restoration of the species throughout its historic range.

“There’s plenty of suitable habitat for bears, especially along the middle Neches River corridor and in the Big Thicket,” Van Dellem says. “But there’s no sign that natural recolonization is happening. The idea that bears are coming back to East Texas was woefully wrong.”

The bear breeding populations in the Ozarks, Ouachitas and Louisiana flourished as a result of active repopulation programs in the 1950s and 1960s. More than 400 black bears were transplanted from Minnesota and Canada to the woods of Arkansas and Louisiana.

The Louisiana black bear, a subspecies of the American black bear, was listed in 1992 as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act. Years of habitat management and restoration efforts proved so successful that the Louisiana black bear was removed from that federal list in 2016. Texas still considers all black bears found within the state as threatened, making it illegal to hunt, harass or kill them.

“The delisting of federal threatened status in Louisiana gives us motivation for an active restoration program in Texas,” Van Dellem says.

“We want to have black bears in Texas,” Evans says, “but we have to balance the views of many different interests. Some like the idea, and some don’t. We would not attempt an active repopulation project without broad public support.”