Aboard the research vessel Katy, 20 boys and girls squat next to buckets holding croakers, crabs and marine animals netted from Redfish Bay off Port Aransas. “What makes some shrimp so big?” asks Annie Dabb, holding a twitching shrimp. A transparent, shapeless comb jellyfish slides through the fingers of Alexis Haynes, 11, who hopes to become a marine scientist. She drops the palm-size jelly, a favorite turtle meal, into a portable aquarium, noting, “It looks like snot.”

As the kids dip out needlefish, tiny flounder and squid, Dana Sjostrom, the Katy’s onboard educator, poses questions to direct their curiosity. “What do you notice about the body shape? The color? The shape of the mouth?”

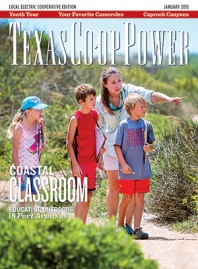

These youngsters are all taking part in one of the five-day Summer Science programs at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute at Port Aransas. The program is designed to immerse students in grades five through eight in hands-on explorations of science. The aim of the course is to ignite each students’ curiosity by exposing them to many facets of marine science and by providing the opportunity to talk with scientists actually conducting research. “This is not information transfer,” Sjostrom explains, “It’s about making sense of what they’re seeing.”

Every morning, the kids observe plants and animals that live in and around Port Aransas. In one session, they study tarpon scales and algae and then dissect a shark. Another time, they explore wetlands, jetty habitats and San José Island beach debris, looking at birds and examining seaweed. Each outing combines research with entertaining activities. The week ends for these apprentice biologists onboard the Katy, a floating classroom where the scientific facts intertwine to create a big picture of the environment, revealing how all parts are meshed into the whole.

Listen up,” says Katy Capt. Stan Dignum to the 20 students and their four guide-educators as they climb aboard the 57-foot boat. “I’m Captain Stan. What I say goes. Your life jackets stay zipped up.”

Sjostrom steps up to define the day’s mission. “Your job is to be curious and get excited about seeing things you haven’t seen before. It’s your job to ask questions about how things work.”

The kids are starting to understand the connections and similarities in biological systems and among different creatures. For example, they note a similarity between the growth patterns of tree rings and the growth rings on tarpon scales and then apply the same logic to the growth layers on clam shells. “If you have no idea what you’re looking at, talk about it, draw it,” Sjostrom suggests. “Does it have antennae? Don’t ask me to tell you the name of a fish until you can tell me something about it.”

Sjostrom’s job during the four-hour cruise around the Intracoastal Waterway and bay combines the tasks of science educator, team captain, deckhand and role model for those considering a career in marine science. Thanks to sessions with experts in plankton, fish migration and ecosystem dynamics, the first four days of Summer Science provide the students a perspective on different habitats around Port Aransas. On the last day, Sjostrom and her crew help the students realize how much more there is to discover and study.

As the Katy surges past the jetty and south into the channel, the students crowd into the bow and spot dolphins frolicking in the water ahead of the boat. A handful of kids squeeze into the pilothouse, seeking both shade and information, fascinated first by the gadgets and then by the job of boat captain. “What’s that thing spinning on top?” asks one student. “Radar,” Capt. Stan answers.

Questioned about the map screen, he moves the cursor around, pointing out jetties and points in the ship channel. “The red line is our course. When I move the wheel, it moves with us.” He explains the array of instruments: the green radar screen that shows everything protruding from the water, GPS that shows speed and position, VHF radio, chart plotter, compass and weather station.

Capt. Stan studied marine biology but preferred to work outside instead of spending long hours in the lab. “The Katy gives me the best of both worlds,” he says. Two of the boys say they want to become captains, but Dominic Ford of Port Aransas wants to become a biologist, admitting the job has other attractions: “I can go scuba diving and fishing.” He participated in Summer Science the previous year, and that experience convinced him to return. In fact, several of the students have attended before, and a few signed on for a second session because each week covers a different theme.

Six and one-half miles from the dock, Sjostrom cautions the revved-up kids. “This is a working research vessel, and there are ways to get hurt. No horsing around.” Then she engages the winch to pull in a fine mesh plankton net, which has been towed along the water’s surface. “What do we already know about plankton? Start brainstorming,” she says, pouring the net’s contents into a tub.

Adult guides Catalina Cuellar, Julie Findley and Cathy Harshman give each child a lavender, plastic, handheld microscope. A water sample gets squirted onto each slide. The children squint into the eyepieces.

“I see plankton!” one of the young scientists shouts.

“Tell me about it. Is it moving? Draw it.”

Hunched over the microscopes balanced on small dry-erase boards, the boys and girls use blue and green pens to draw ovals with multiple short legs, squares with legs and antennae, wiggling worm-like shapes, and something that resembles the ridged edge of a coin as seen from the side.

“Do you see brown things that look like coins?” Cuellar asks. “Those are diatoms. Copepods eat them. And who eats copepods?” Several know the answer and call it out: “Small fish.”

Emery Jones, 11, who with the rest of the class pressed algae onto paper earlier in the week, draws seaweed on her board and copies it into her journal.

For better viewing, Cuellar guides them to the roofed wet lab where slides under a gooseneck microscope show up on a wall-mounted monitor, magnified 40 to 100 times larger than life. Surprising colors—blue, orange, green—characterize the odd shapes. The crab larva looks like a little alien. “Oh, I see it now. It has one eye in the middle.”

Cuellar, who is working toward a doctorate in marine ecology, says Summer Science kids quiz her about the work she does. “They tell me, ‘I’d like to be a scientist, but it sounds too hard.’ They think there’s a mystery about being a scientist or that it is beyond them. Of course, some are intrigued by the idea of diving for a living or fishing every day. The Summer Science program gets them involved in real science.” Cuellar understands the lure of the deep because scuba diving as a teenager got her involved in marine biology and onto her career path. “You get exposed to the marine environment, and you fall in love.”

In Redfish Bay, the winch hauls in a net filled with creatures that live on and in the bottom mud. Sjostrom pours the mud into boxes with screen bottoms. Three to four kids cluster around each box, sorting through shell fragments and seaweed. “I’ve got a worm on my leg,” announces a girl with blond braids. She learns the wire-thin worms eat everything that falls into the mud, processing nutrients in a process similar to that used by earthworms.

A captivating brittle star waves five thin arms like streamers in the wind. How does it do that? “They put water pressure inside their arms to move them,” Sjostrom explains.

For a closer look, kids use tweezers to put creatures under the gooseneck scope. On the big monitor, a bristly, orange, segmented creature changes colors. “I wonder what that is,” one boy says. “Is it eating the seaweed?” Around him, kids sketch the enlarged images into their journals.

The mud sample shows that water doesn’t have to be clear blue to support all kinds of life forms. “When you get a mouthful of salt water, and it’s crunchy, you think it’s sand. It’s not,” Sjostrom says. What’s crunching are tiny invertebrates.

With the thought of marine invertebrates, snack time brings watermelon.

The third trawl of the net catches free-swimming animals. Laughing gulls hover, hoping for a free meal as Sjostrom pours croakers, anchovies, a flounder, ribbon fish, squid, crabs and shrimp into a large tub, scooping them into smaller buckets and the live well. “What I want you to do is look at the fish closely. Open up their mouths,” she says.

The kids grasp fish and shrimp and drop them into handheld circle aquariums, made of two squares of Plexiglas that sandwich a 2-inch slice of 6-inch PVC pipe. A gray semi-rectangular sponge is not wearing square pants or squirting water. A boy opens and closes an anchovy’s mouth, demonstrating how the wide gape helps it snatch plankton. Cuellar and Sjostrom page through the “Key to Common Inshore Crabs of Texas,” trying to identify a specimen.

The final trawl in the ship channel brings up more shrimp and different fish. Why? “Check it out, guys,” Sjostrom says. “We have some seaweed that’s pretty cool.” Holding what looks like a mess of transparent rice noodles, she identifies it as a colonial animal.

Going back to the dock, the kids continue to dip into the tanks, examining shrimp and tossing dead anchovies to noisy gulls. The junior scientists pay no attention to the water streaming from the holding tank drain, washing over their sneakers or the bright pink of a roseate spoonbill flying astern.

The favorite finds of the day include the sea horse, moonfish and ribbonfish. The high point of the week, the kids agree, was roaming around San José Island. “It’s all fun, even cutting up the shark,” says Emery. “You have freedom to explore and ask questions.”

——————–

Eileen Mattei, a member of Nueces and Magic Valley ECs, lives in Harlingen.