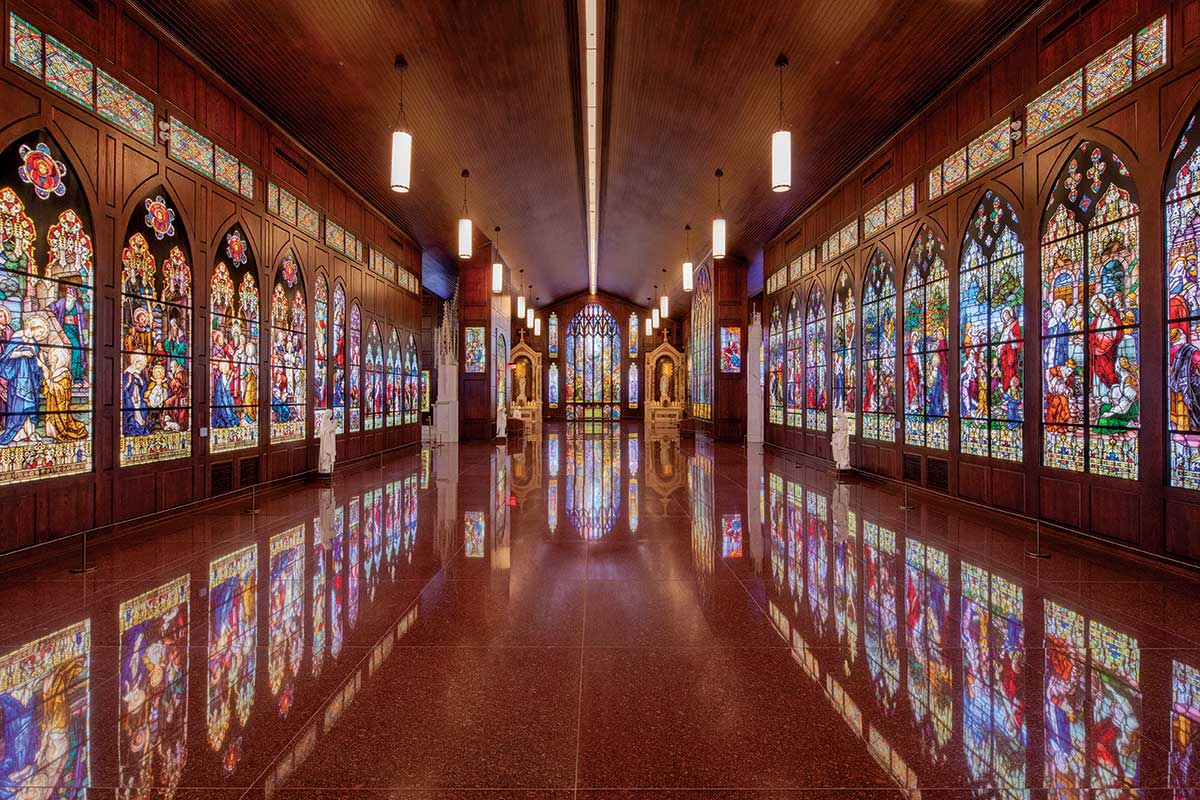

I pull open the door of the Gelman Stained Glass Museum and step inside a kaleidoscope. More than 150 stained-glass windows and their reflections in the highly polished red granite floor immerse me in light, color and space. Then my eyes and brain begin to separate the profusion of shapes and colors into windows of religious scenes ranging from 10 to 25 feet tall, illuminated by what seems to be heavenly light.

Inside a gray stone building just off the highway in the heart of San Juan, in the Rio Grande Valley, the narrow, cross-shaped space is cool and dim. Most of the stained-glass windows in the museum, which opened in November 2021, originally graced now-closed East Coast churches, where they had been dedicated as memorials to departed loved ones. In their safe, new climate-controlled home, the complex LED arrays that backlight all the windows provide a steady, otherworldly glow that compensates for variations in the thickness of the glass and paint amid the absence of natural light.

About 30 years ago, an auction catalog prompted Lawrence Gelman, an Edinburg anesthesiologist, to go to Atlanta, Georgia, to view a stained-glass window as it was being repaired. He later phoned in his winning auction bid and purchased the 4-by-7-foot landscape. “There’s something about the vividness of colors when light passes through stained glass,” Gelman says.

Captivated by the art, Gelman delved into the history and mastery involved, collecting more and more stained-glass windows until he had enough to fill a museum, which he chose to locate in San Juan, near the Basilica of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle. That shrine annually receives more than 1 million visitors, an audience primed to appreciate Gelman’s collection.

“Dr. Gelman wanted to replicate a sacred, transcendental experience,” says Miriam Cepeda, the museum’s director.

He has succeeded, no question.

Te Deum, the Gelman Stained Glass Museum’s largest work, invites contemplation.

John Faulk

Created between 1880 and 1910 by 12 master glasswork artists and studios of the art nouveau era, the works comprise the largest American museum collection of stained-glass windows. And with 71 Louis Comfort Tiffany windows, the Gelman has the largest collection of Tiffany glass windows in the U.S. Other noted glass artists represented here include John La Farge, Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast and those at J&R Lamb Studios—the oldest continuously operating glass studio in the nation, dating to 1857.

Cepeda gives me a quick explanation of stained glass. Traditionally, stained glass was actually painted glass.

The glass panels are supported and joined by flexible channels of lead called cames—and, in some cases, by copper foil. Tiffany Studios popularized the use of opalescent glass and layered glass to achieve shimmering, flowing colors for landscapes. Looking closely, I notice that even the faces and hands of Christ, the apostles and other religious figures have been painted onto the glass. Many of the windows represent biblical scenes, such as the Nativity, flight into Egypt, Good Shepherd, and Madonna and child, as interpreted by the artists. But La Farge’s works here mostly portray medieval scenes.

The vivid jewel tones of Franz Mayer’s stained-glass windows contrast with the luminous blues and greens of Tiffany Studios’ masterpieces, such as the Te Deum. The museum is just one glorious work of art after another.

The Good Shepherd, baptism of Jesus and flight into Egypt are among the biblical stories portrayed in stained glass framed by red oak paneling.

John Faulk

Religion Enthroned, right, is one of two stained-glass windows created by La Casa del Vitral for the Gelman. The Edinburg art studio restored and installed the museum’s stained-glass windows.

John Faulk

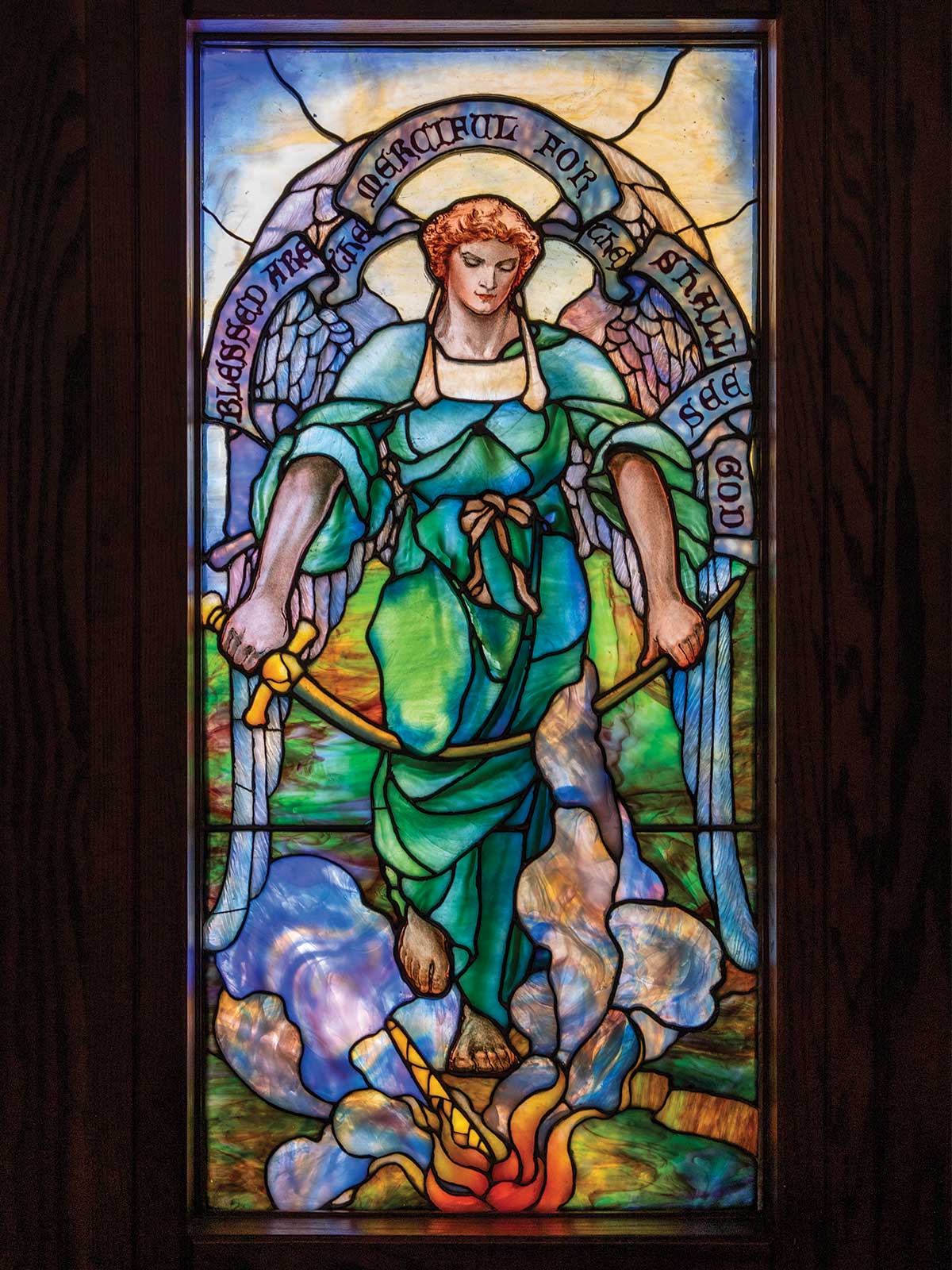

An eye-catching group of eight Tiffany windows portrays angels as stern warriors and loving guardians presenting the Beatitudes—sayings attributed to Jesus. These windows adorned a private mausoleum, out of the public eye for 108 years, until Gelman put them on display.

Similar memorial inscriptions evoke a bygone time, such as “To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of Charles Chamberlain Gay 1835–1913.” One narrow window honors the memory of three women who died in the wreck of a ship called the Paul Jones in January 1899 in the Gulf of Mexico.

The small but magnificent north chapel shimmers with windows rich in pastels. In the south chapel, a large pipe organ and an electronic organ, backed by superb sound systems, enhance the sensory feast. The museum hosts orchestral and chamber music concerts and has been the setting for weddings, workshops and secular celebrations.

The museum chose not to add interpretive displays to the windows, instead providing guests a compact map with QR codes that, with a click of your phone camera, link to in-depth descriptions of the windows, their artists and their techniques. The map also identifies the marble altars, statues and mosaics throughout the building.

La Casa del Vitral, an art studio in Edinburg, took on the restoration of the century-old windows and installed the glass art in the museum. They also made replicas of several windows held in other museums.

Admission to the Gelman Museum is by appointment only, made through its website, gelmanmuseum.org.

Once visitors are inside, benches invite sitting and contemplating. Subtle light washes over me while I listen to recorded voices raised in Gregorian chant. Peace and beauty.

Backlighting allows the true colors of the stained, painted and layered glass to show through, regardless of the time of day.

John Faulk

The museum boasts eight Tiffany stained-glass windows depicting the Beatitudes, or blessings, including Blessed Are the Merciful.

John Faulk

The nave of the cross-shaped museum immerses visitors in the color and artistry of century-old stained-glass windows and their reflection in the highly polished granite floor.

John Faulk