A pint-size poet steps up to a microphone stand that towers over her. It’s a February morning in far West Texas as Bethia Baize, 5, recites The Well-Used Cayuse, inspired by her horse. Emcee Karen McGuire holds the mic at the kindergartener’s height. Bethia speaks softly, from memory, to a rapt audience in a Sul Ross State University lecture hall, her voice and words kicking off a youth poetry contest. When she’s finished, the room thunders with applause, and Bethia claims the first-place plaque for her age group.

For the rest of the session, which is one of dozens at the annual Lone Star Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Alpine, the energy in the room is electric. Parents, grandparents and other supporters fill every seat and line the walls as 16 young poets recite their award-winning works about cattle and coyotes, cowboys and cowgirls, and the rhythms of ranch life. The room pulses with pride, love and nerves—like a spelling bee, but giddier and more exuberant.

Bethia’s aunt, Elizabeth Baize, a member of the poetry gathering’s board of directors, co-hosted the youth poetry contest with McGuire, also a board member. In the weeks before the event, Baize visits area schools to spur students to enter. She encourages them to talk with older relatives who might have ranch life experience and to look at photographs or paintings that might inspire them to write a story in the form of a poem.

It’s no mean feat winnowing down the annual crop of entries to the winners. As the judges read the entries, “there are giggles and good belly laughs, tears and sniffles, and ‘Oh my, listen to this!’ ” McGuire says.

The future of cowboy poetry is in good hands.

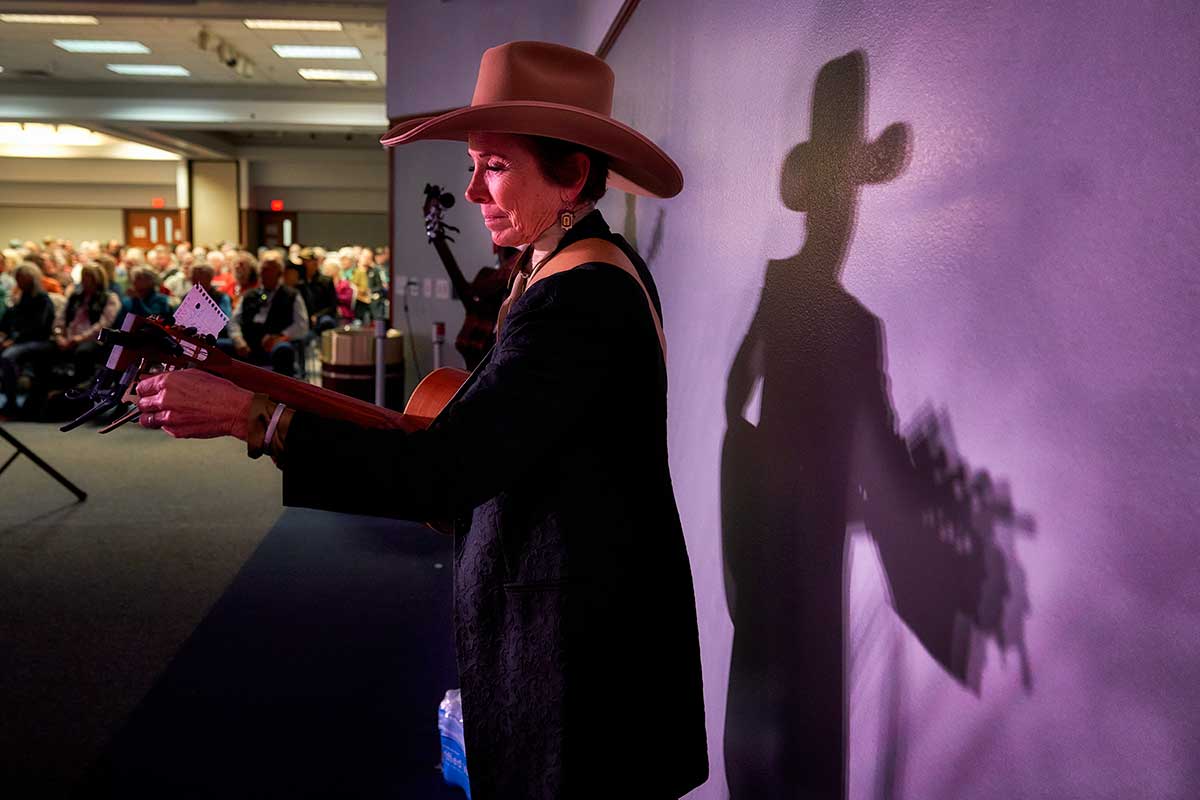

Juni Fisher from San Joaquin Valley, California, tunes up before her performance.

Dave Shafer

Mornings begin outside with cowboy coffee over a fire.

Dave Shafer

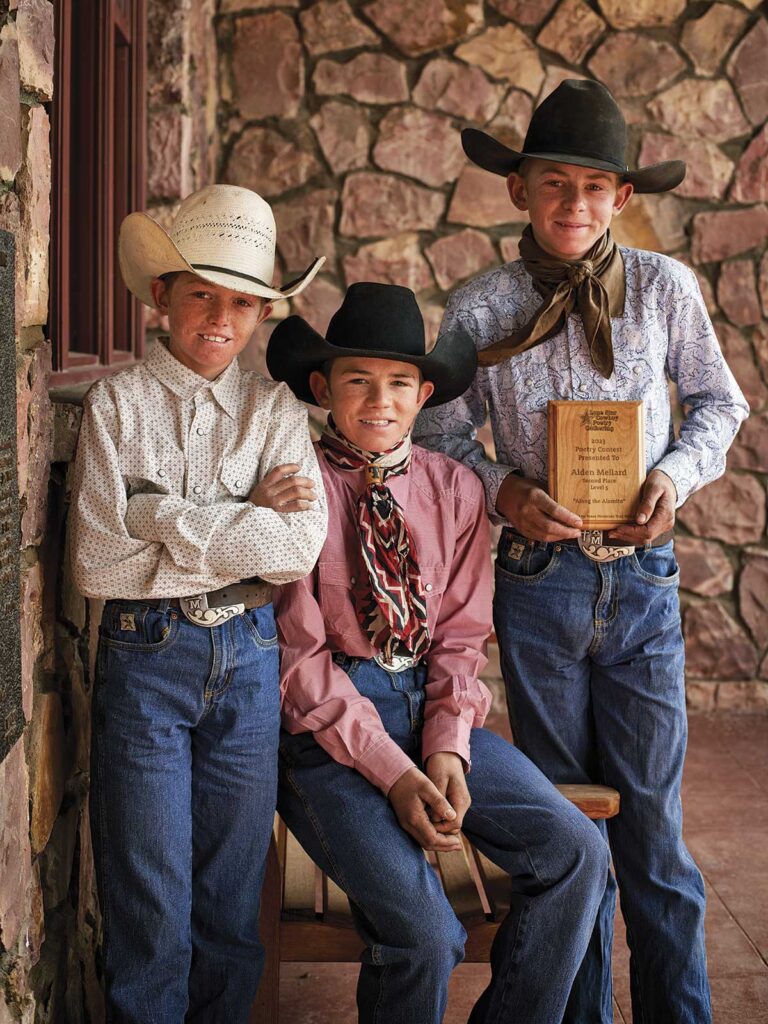

The Mellard brothers from outside Marfa found success during the youth poetry contest. From left, Travis and Thomas earned honorable mentions, and Aiden claimed second place in his age group.

Dave Shafer

McGuire and Baize—and scores of organizers and volunteers—work hard to ensure that future. They helped stage this year’s gathering, which drew north of 2,200 attendees and featured 40-plus performers of cowboy poetry, which encompasses music, spoken-word poetry and storytelling by ranch hands, cowboys and cowgirls and has been enshrined as an oral tradition by Library of Congress folklorists.

In North America, the Texas gathering is second in size only to the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, according to Bob Saul, the gathering’s volunteer event producer. This year’s event delivered at least five times as many free performances and sessions as ticketed ones. That’s by design, Saul says.

“We want people to come. Some of the cowboy poetry gatherings have gone to all paid; there’s nothing free you can go to,” Saul, 79, says. “But our board has decided that we’re going to carry on the tradition and the mission, that we will do our best to provide cowboy poetry, as much of it as possible, free of charge.

“In other words, it’s for ranching families.”

In 2019, Saul was in the audience at the Texas Cowboy Poetry Gathering (the original iteration of the event in Alpine) when it was announced that that year’s gathering would be the last. Saul immediately began canvassing for volunteers to keep the event, or some semblance of it, alive.

“I just started talking to people and asking if they would be willing to help, if we could get it restarted, would they volunteer,” Saul says. “And I came back to Fort Worth after two days with 142 email addresses in my pocket.”

Over several months, Bob and his wife, Nancy Saul, a graphic designer who creates the gathering’s annual programs, made more than a dozen 15-hour round trips between their North Texas home and Alpine to help the new gathering find its footing. Those pilgrimages were rooted in a deep affinity.

Kristyn Harris calls the gathering a place for “sharing your art, sharing yourself.”

Dave Shafer

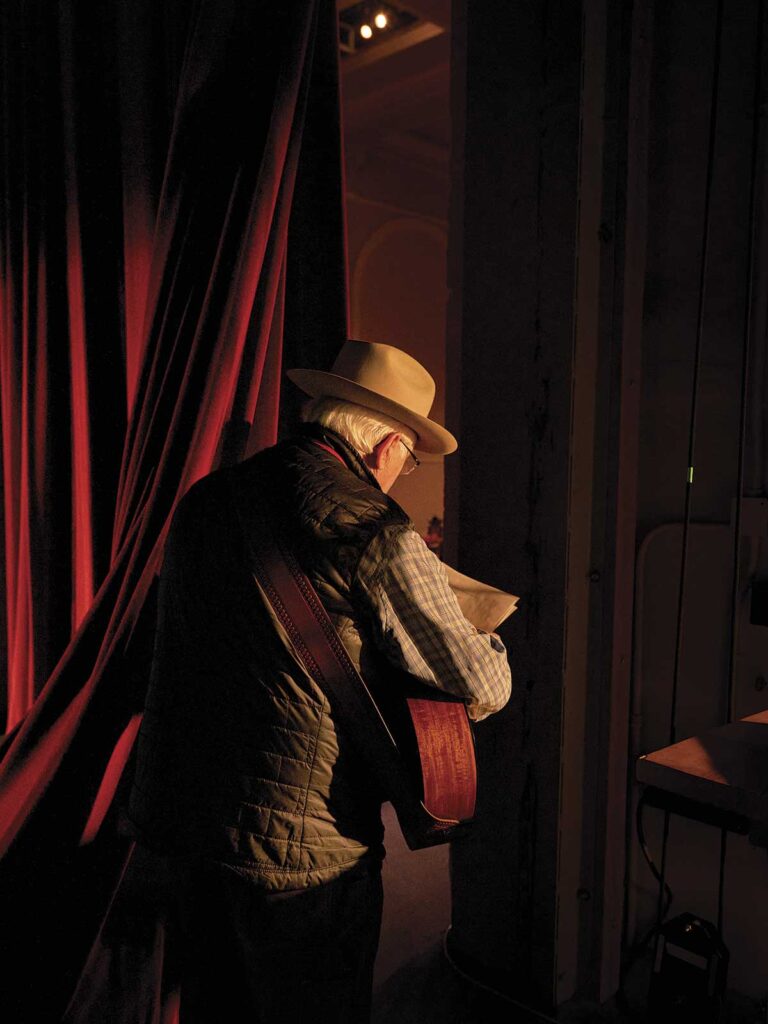

Andy Wilkinson of Lubbock reviews his notes backstage.

Dave Shafer

Jack George, a 16-year-old performer from Quemado, New Mexico.

Dave Shafer

“Poetry is a language of the heart,” Saul says. “It’s a language of emotion. Prose is language, but poetry is what sears it into our being. And today poetry is mostly academic. You don’t hear, like you used to, people going to hear people quote poetry; except when you go hear the fishermen and the miners and the loggers and the cowboys.

“Those kinds of industries, where people are working long hours and they are more alone, they’ve got time to think. And they’ve got time to sing. And they’ve got time to recite to themselves.”

That reverence reverberates across the gathering, which takes place the third weekend in February. At sessions with names like Western Harmony, Ranch Women and Working Ranch Families, audiences are focused and present, bearers of a quietude punctuated only by bursts of applause or laughter. Almost every cellphone is out of sight, every eye on the performers. Those wearing cowboy hats are kindly asked to remove them so as not to obstruct the view for others.

Kay Nowell, co-chair of the gathering, describes the genre as a celebration of a tradition and a way of life. “What cowboy poetry is is real,” she says. “People get taken into rural people’s life, and they get to experience it through their poems and their songs. It’s a culture that adheres to a code.”

Nowell has conformed to that code for decades. She was a featured poet at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in 1989, which led to an appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, where she recited her poem A What??!!

A chuck wagon breakfast kicks off each day of the Alpine gathering. This year temperatures stay below freezing as Alpine Lions Club members serve scrambled eggs and biscuits and gravy in the peaceful Poet’s Grove at Kokernot Park. Cups of coffee skate across iced-over tables as the sun crests a hill, and a blazing firepit and easy conversation counter the chill.

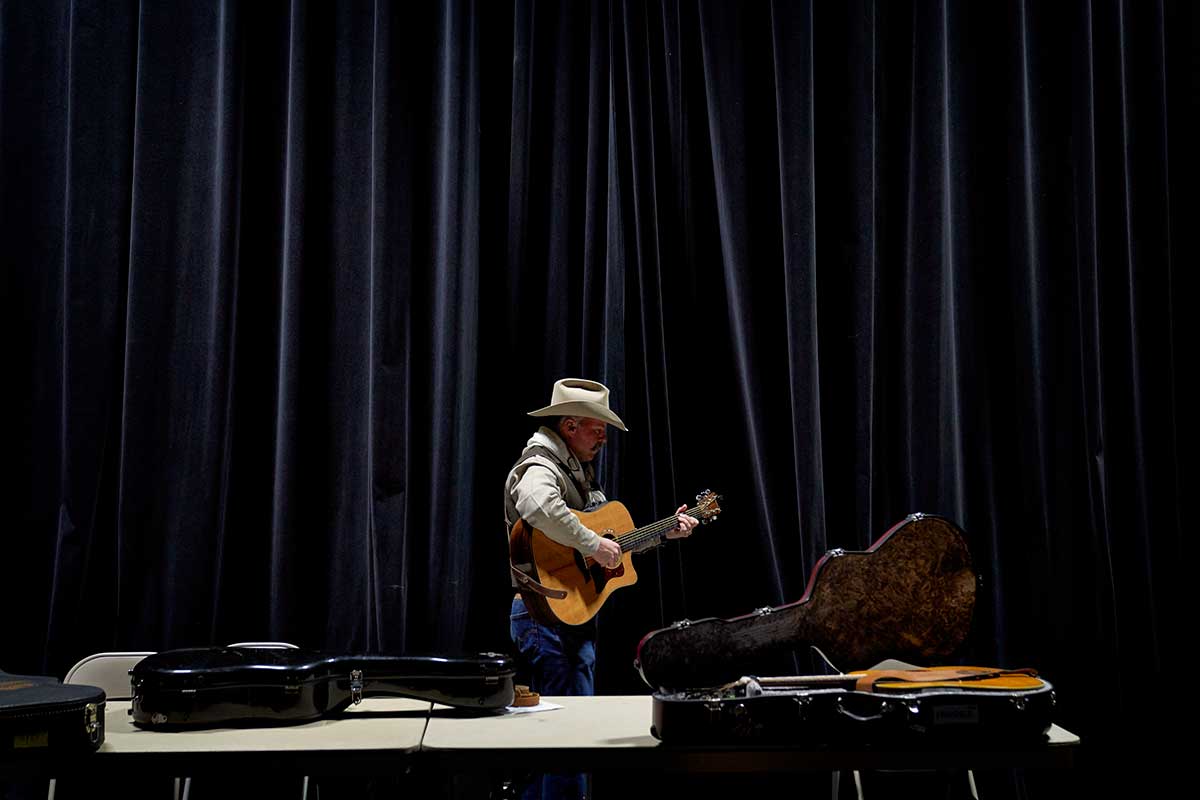

Nevada rancher Waddie Mitchell has been a performing poet for decades.

Dave Shafer

Randy Rieman of Choteau, Montana, has had a love affair with the spoken word for more than 40 years.

Dave Shafer

Maggie Rose Hedges is one of the youngest performers at the gathering.

Dave Shafer

The spirit of camaraderie and mindful attention extends to the gathering’s open mic sessions, another free daily offering open to the public. Musicians and spoken-word performers sign up in advance, wait for their names to be called and then amble down to speak, sing or play their piece. Jan Hartman is up first Friday and plays Amazing Grace and taps on her fife.

The instrument “has its own sweet sound, I think,” Hartman says. “It has more of a country sound than an orchestra sound.” Hartman, who lives in Alpine and has participated in the open mic for the past five years, says she still gets nervous before she plays. It’s worth it, though.

“It makes you stand out a little bit, just to be able to play before some people, and be able to tell a testimony or a story or, there again, a poem that you’ve heard,” Hartman says. “So it just makes you feel a little special.”

Fiddler Maggie Rose Hedges.

Dave Shafer

In Alpine’s cold early mornings, hardy attendees at the chuck wagon breakfast warm themselves near a campfire that is baking biscuits in cast-iron Dutch ovens.

Dave Shafer

Burleson singer-songwriter Kristyn Harris at the Lone Star Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

Dave Shafer

One of the musicians Hartman most looks forward to each year is Kristyn Harris, who first appeared at the gathering’s open mic more than a decade ago. The singer and yodeler, songwriter, swing rhythm guitarist, and winner of multiple International Western Music Association awards performed in several sessions at this year’s event.

“The audiences here are really here to soak it up, and you really connect with them,” says Harris, a Burleson resident and member of United Cooperative Services, an electric cooperative in the Metroplex. “Rather than just performing for people, it’s like sharing your art, sharing yourself and sharing your history.”

In a Saturday afternoon show, Harris covers the jazz standard All of Me in a Western Swing style on the heels of Juni Fisher’s spare, moving rendition of Simon and Garfunkel’s folk classic The Boxer. The talent on display is dizzying, the audience enraptured, and the trio onstage—with poet Amy Hale emceeing—exude a sisterhood in their banter and backing of each other.

“I’ve played festivals that are festivals, and then the gathering is different,” Harris says. “There are performers here that I really look up to, that I could see as celebrities, but here no one is a big celebrity.”

Loren Schooley, a musician from Marfa who works in information technology and performs at Friday’s open mic, echoes that sentiment. “Usually you go to a gig, and then you see the band or two, and then that’s it,” Schooley says. “But here it’s almost like a conference. You never know what you’re going to step into if you go into some of these rooms. And when you find the sweet spot—I’ve shed more tears here and laughter. You just can’t get that anywhere else.”

The gathering’s performers are similarly compelled.

Rachel and Tommy Mellard, with daughter Dalleigh, watch their son Aiden recite his poem in the youth poetry contest. Aiden finished in second place.

Dave Shafer

Midland’s Chris Ryden.

Dave Shafer

“The best way I can describe it is it’s family,” Harris says. “There’s a big, big, big Texas spirit about this gathering that’s also different from some other poetry gatherings that are in other parts of the country. Everyone is just so Texan: friendly, wants to give you a big hug and just gives you that warm feeling.”

The sweet spots and Texas spirit alchemize into what Nowell calls magic sessions. “They’re intoxicating,” she says. “A lot of times when I’ve been in one you just throw away your setlist and feed off the last guy’s stuff. And it’s all one piece. A lot’s going on up there on that stage, and the audience feels it, and they’re taken along on the ride. But the performers are having a blast.”

Community investment helps sustain that improvisation. “Volunteers are critical to this,” Nowell says. “We can’t put this on without support from members and support from sponsors.”

Tradition and fortitude are woven into the gathering’s rough-hewn fabric. “The Lone Star is bound and determined to keep it cowboy,” Nowell says. “Weather, government, markets; it’s a hard life. But it’s something people want to raise their children in.”

An ensemble of artists performs the finale, a tribute to Charles Goodnight.

Dave Shafer