Every spring, pastures, rights-of-way, easements and meadows along Texas roadways erupt into Technicolor splendor. Viewing wildflowers preoccupies enthusiasts all over the state. Searching out, ogling and photographing lavish fields of yellow black-eyed Susans, red-and-yellow Indian blanket, luminous-purple winecups and deep red Drummond phlox becomes a spectator sport. Two hotlines (one from the Texas Department of Transportation, the other at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center) keep callers apprised of new flower sightings from March 1 through the middle of April.

The holy grail of wildflowers is, of course, the bluebonnet, which is the Texas state flower. So popular is the prolific lupine, whose blue petals resemble the shape of a bonnet worn by pioneer women, that it has generated artistic genres unique to Texas: the bluebonnet painting and the family photograph featuring a child nestled into billowing swaths of the flowers.

“People assume that all wildflowers are native to Texas,” says Damon Waitt, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center senior botanist.

Tom Uhlenbrock | St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Don’t, however, leap to the conclusion that all is well in the wildflower world. “The robustness of the spring bloom is not an indicator of the general health of their environment,” notes Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Senior Botanist Damon Waitt. The fact that the flowers bloom at all is a barometer of the gracious cooperation of temperature, rain, sunshine and the plants’ genetic hardiness. It is also a testament to the determination of a small battalion of people who work endlessly to improve the ever-shaky odds that winecups, Indian paintbrush, bluebonnets and other native flowering plants will survive.

This task is challenging. Despite the show of vigor these wildflowers muster once a year, the threat to their well-being is constant, and it’s right in their midst. “People assume that all wildflowers are native to Texas,” Waitt says, “but the flowers have become less native over the last 20 years.” The reason? The relentless influx of invasives—plants like the aptly named bastard cabbage, which appears in clusters with pretty little yellow flowers. The plant flourishes from Port Aransas to Fort Worth and is hell-bent on pushing westward to El Paso.

“Bastard cabbage is opportunistic,” says Waitt. “It loves roadsides and disturbed areas.” There’s plenty wrong with that scenario. “It’s pre-empting the native wildflowers and taking up space where they would ordinarily grow.”

If bastard cabbage were just an isolated offender, there might be less cause for alarm. But the influx of invasives has become so cataclysmic that in 2005, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center partnered with the Texas A&M Forest Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas Master Naturalists, Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, and other environmental groups to create texasinvasives.org. Coordinated at the Wildflower Center, the website partnership allows government agencies, nonprofits, academia and conservation organizations to share best practices and information with the public. “This is a problem that demands the public’s help,” says director Justin Bush, emphasizing the immensity of scope. “It affects every section of land and every waterway in the state.”

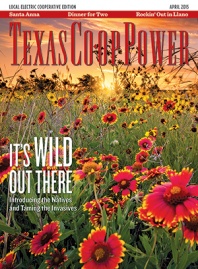

Sunflowers and Indian Blankets under a Texas sky.

© Dean Fikar | TDF Photography

Citizen scientist Mark Staerkel pulls down invasive Japanese climbing fern at Jesse James Park in Spring, Texas.

Will Van Overbeek

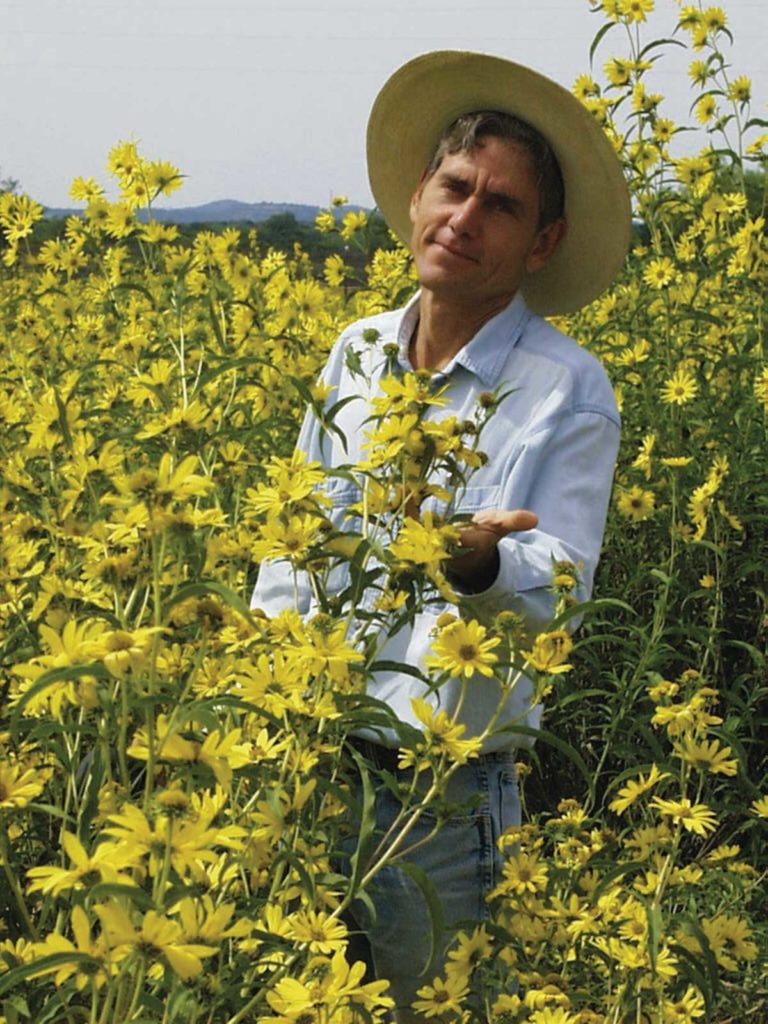

Bill Neiman built his business, Native American Seed, around Texas wildflowers.

Courtesy Native American Seed

Texas depends on grassroots support to fight this fight. And that’s where texasinvasives.org’s Citizen Scientists program comes in. About 2,400 volunteers have completed the training necessary to seek out and report outbreaks of the 79 environmentally harmful invasive plant species targeted. Citizen scientists contribute important data to local and national resource managers who, in turn, coordinate appropriate responses to control the spread of unwanted invaders. “The premise is simple: To move all of us beyond awareness and into action,” Bush says.

One such citizen scientist taking action is Mark Staerkel of Spring. The semiretired plumbing and hardware manufacturer’s representative joined Citizen Scientists as part of the 40 hours of service time required for master naturalist certification. Scouting for invasives had a familiar ring: “It reminded me of what I did as an assistant Boy Scout master for 30 years.” Although Staerkel has always been outdoorsy, he isn’t a gardener.

You can spot Staerkel at one of his favorite haunts, Jesse James Park in Spring. He’s the one carrying a big plastic bag and pulling up the vine-like Japanese climbing fern, which, if left uncontrolled, will smother entire trees. The fern also produces a thick groundcover that thwarts native seed germination. “I’d never even heard of it,” says Staerkel, “but it was easy to identify and is everywhere in Houston.”

The program has changed Staerkel’s view of what he sees in the landscape. “I used to enjoy looking at some of these plants, like the crepe myrtle or the Japanese mimosa,” says the citizen scientist. “But now that I know that they prevent natives from growing, and birds and insects can’t eat them, I don’t think the way I used to.”

Neither does Bill Neiman. Throughout the 1970s to the mid-1980s, Neiman ran a successful landscaping business that addressed the needs of urban Dallas as well as the burgeoning suburbs that were scraping flat the plains north of Dallas. Neiman and his crew of 45 built hardscapes, planted big trees and installed vast irrigation systems. But then the drought of 1980 hit, and Neiman noticed something: “Those intensive landscapes I’d installed in Highland Park were failing.”

At the time, no one thought of Asian jasmine, Japanese boxwood, Pakistani crape myrtle and African Bermuda grass as nonnative, much less as invasive. On the road home one day, Neiman saw the light. “I pulled over on the side of the road to stare at flowers that were blooming despite no rain and temperatures over 100 degrees,” he recalls. “I realized that these plants were all natives. They’d evolved here without fertilizer, herbicides, pesticides and irrigation systems.” That realization changed everything Neiman had lived for. “I realized I was part of the problem.”

Wildflowers have a symbiotic relationship with other wildlife.

Courtesy Native American Seed

Native American Seed’s crop of standing cypress

Courtesy Native American Seed

Neiman went home and shifted everything in his nursery to native plants. He sowed his first seed farm and had his first harvest in 1988. In the summer of 1995, Neiman and his family moved to the Hill Country, on the Llano River just outside of Junction, and founded Native American Seed. The company harvests native seeds there and at other farms on the Coastal Prairies and in the Piney Woods for a range of seeds to suit all areas of Texas. Apache Plateau, Bee Happy, Hummers & Singers, Deer Resistant and other mixes offer options to suit personal tastes and geography. Some, such as Lady Bird’s Legacy Wildflower mix, are rebranded in packets by civic, nonprofit, academic and business groups (including Texas Electric Cooperatives), with profits going to the Wildflower Center. TxDOT also is a customer, seeding state roadways with the mixes when Neiman is the low bidder on the contract. “What we are doing,” says Neiman, “is providing our customers with an ecosystem in a bag. It’s a way to save the legendary DNA of these flowers.”

The battle to save Texas’ wildflowers has become more urgent in the past two decades, as Wildflower Center botanist Waitt noted. But people have responded to the call for action. There are more than 2,000 other volunteers like Staerkel chopping down, pulling up and ripping out invasives all over the state. And there are gardeners, inspired by Neiman’s unrelenting message urging awareness, who are replacing their boxwood-lined gardens with Texas native meadows. Neiman is optimistic. “It’s all in the dialogue,” he says. “It’s the only way we are going to do it. And that’s something one person can do.”

There are plenty of ways a person can continue the dialogue. In fact, there’s a license plate that helps: The horned lizard plate funds texasinvasives.org and conservation efforts in the state. And, new this year, a wildflower license plate delivers 100 percent of its profits to the Wildflower Center. Affixing one of these plates to your car or trailer lets your vehicle do the talking—and it’s just in time for wildflower season, when what’s blooming is the season’s hottest topic.