Most museums start with large corporate grants, city planning and decades of advance work before finally opening to a community.

But the Naranjo Museum of Natural History in Lufkin got its start when Mary Ann Naranjo grew tired of her husband’s archaeological finds cluttering up their home. “Our dining room had a prehistoric rhino, a woolly mammoth and a saber-toothed tiger, along with other bones and things. It was hard to eat dinner staring at a mammoth,” Naranjo said.

Her husband is paleontologist and archeologist Neal Naranjo.

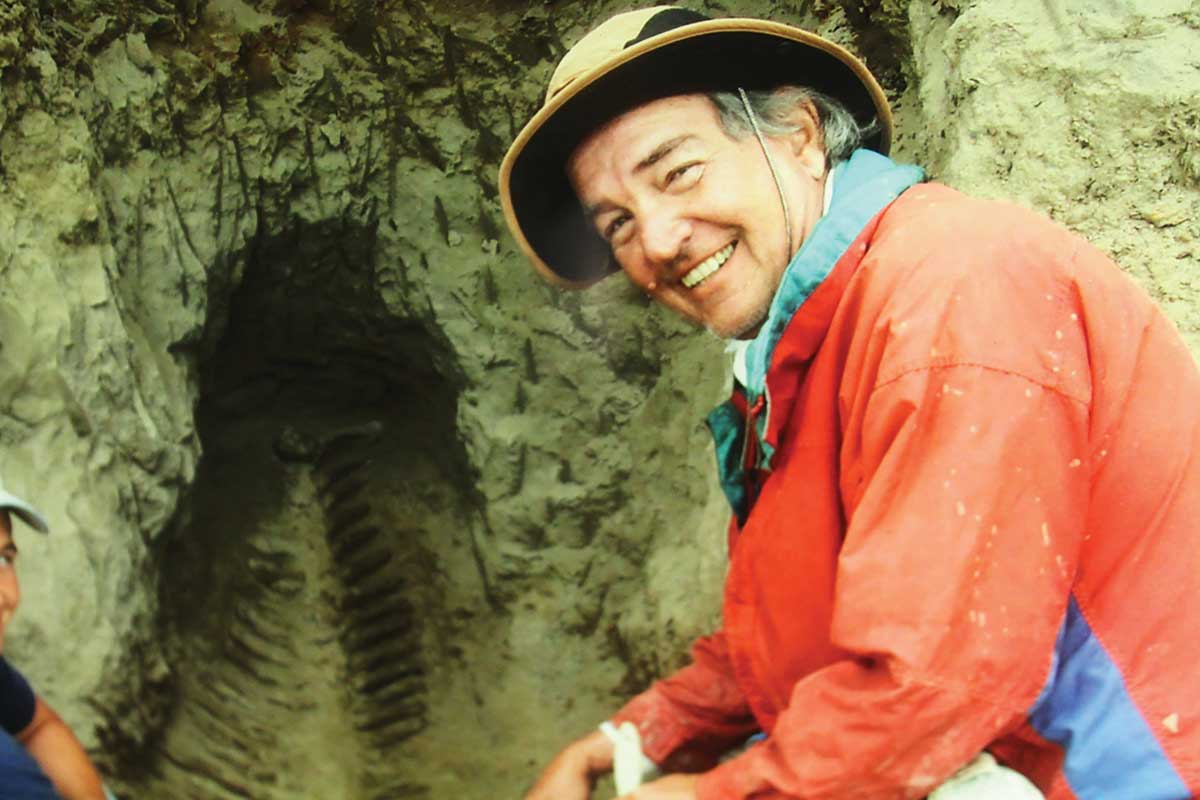

Neal Naranjo and his wife, Mary Ann, were instrumental in the opening of the museum.

“I told him, ‘Why don’t you open a museum to house all this stuff?’ And sure enough, he did.”

That was in 2012, but Neal Naranjo’s exploits began long before that. He credits stepping on a 12,000-year-old arrowhead while digging for clamshells near Woodville when he was just 5 for sparking his interest in Earth history. Since then, among other achievements, he’s earned a doctorate in neuropsychology from the University of Southern California, become a professor at Harvard Medical School and unearthed one of only two known totally intact hadrosaurs in the world.

“I imagine the other one is probably on display in someone’s regal living room somewhere in the Middle East,” Neal Naranjo said. “We call this one Mary Ann, after my wife.”

While its footprint isn’t as large as that of Houston’s Museum of Natural Science, the Naranjo Museum’s collection rivals its big-city counterpart, with everything from the hadrosaur to moon rocks gleaned from the Apollo 14 mission to ancient coins and pottery.

But it’s the dinosaurs inside the museum that cause jaws to drop when visitors enter.

Even though the hadrosaur is almost tiny in comparison to a towering Tyrannosaurus rex just a few yards away, it’s the 68-million-year-old Mary Ann that immediately gets museumgoers’ attention.

Neal Naranjo poses next to the fully intact skeleton of a hadrosaur, discovered on one of his archaeological digs in Montana.

“We were on a dig in Montana when we first started finding pieces,” Naranjo said. “It’s a very slow and tedious process, done by hand, slowly scraping away millions of years of fossilized clay, all the while being careful not to break any pieces. This one was particularly exciting because we found a femur, then another, then a rib and eventually the whole skeleton.”

Naranjo said that it is very unusual to find a dinosaur intact, especially one that is all in the same place. “Most times they’ll be spread out over a football field-sized area,” he said. “This one must have just dropped dead in that spot and was never disturbed for almost 70 million years.”

An upright dinosaur that greets visitors upon entry to the museum is a precursor to what they’ll find among the other exhibits.

While the digging and discovery was exhilarating for Naranjo and his three assistants, getting the bones out of the ground and back to Lufkin was anything but easy.

“Because of the location, we were not able to get any motorized vehicles within a couple of miles of the dig site,” he said. “So we rolled the pieces up in a tarp, and with two of us in the front and two in the back we’d carry it a hundred yards, set it down, catch our breath, and repeat the whole process until we got to the truck. Oh, we also had to cross a river, which was about chest deep, so part of the time we had the bones hoisted above our heads.”

The frontal view of the hadrosaur shows one of its horns and its eye sockets.

The leg of the hadrosaur was fossilized with skin intact, showing the texture of the hide. Finding bones with skin is extremely rare, and this is one of only a few such specimens in the world.

One unique feature of the hadrosaur is its feet. No one had ever before found enough of a hadrosaur to know what kind of feet it had, so it was assumed that like most dinosaurs of its size, it had claws. Naranjo proved otherwise.

“We X-rayed the feet to see more of the backstory, and we can tell from even using the naked eye that her feet were very padded and covered with skin about an inch and a half thick. They were more like hooves. The soles were also very prickly, almost like touching a bed of nails, so she was almost walking on air. I like to say other dinosaurs had cheap sneakers and Mary Ann had Air Jordans. It made it much easier to get around in what we believe was a swampy environment, due to the number of fossilized leaves, pine cones and fly larva we found near her.”

Naranjo took one of the feet of the hadrosaur to be X-rayed, along with several dinosaur eggs he found. The hadrosaur had padded feet rather than claws.

Inside the museum, in addition to the T. rex and Mary Ann, there are other dinosaurs, whole or in part, that were found on Naranjo’s numerous digs over the past half-century.

Despite the comprehensive trove of data on prehistoric life derived from bones, remains and even fossilized excrement (also on display at the museum), the mystery remains: What caused the sudden demise of the dinosaurs?

“I can answer that one pretty easily,” Naranjo said. “The answer lies in the Chicxulub crater off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The meteor was the size of the city of Lufkin and hit the earth at 22,000 miles per hour 66 million years ago, long before any humans were around. When it hit, it shot tons of stuff into the atmosphere, things like iridium, which is not of this Earth, and caused a tidal wave and fires across the entire planet. Little chunks of meteor continued to fall, and most folks believe that is what killed off the dinosaurs. It happened very fast; it wasn’t an evolutionary thing. It was like, BANG, and they’re gone.”

The hadrosaur isn’t the only prehistoric fossil on display at the museum. Visitors can also find a Dunkleosteus, more than likely the first and most powerful fish ever to exist. It was the dominant carnivorous predator during the Devonian Period, and while it was around for about 50 million years, it eventually became extinct and left no discernible descendants.

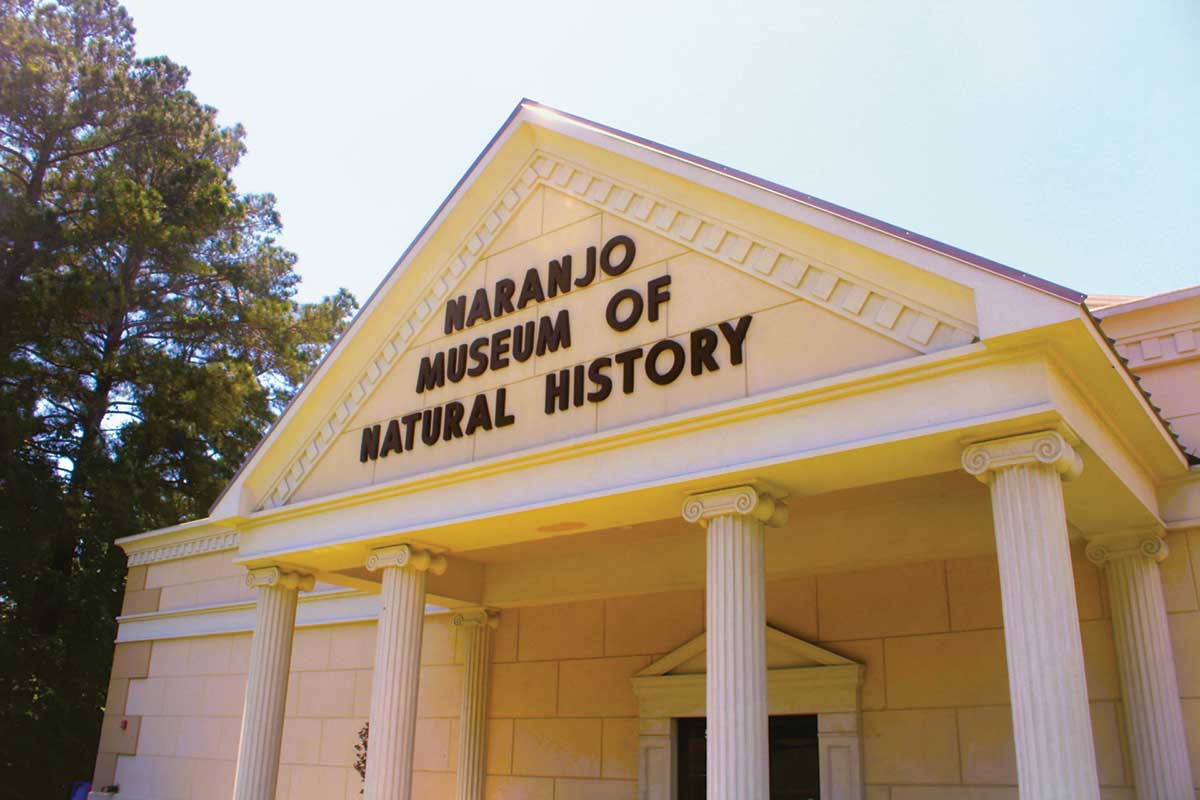

The museum is located on U.S. Highway 59, just south of Lufkin.

Another display at the Naranjo Museum shows the Carboniferous Period. It was during this time that giant dragonflies, centipedes and cockroaches roamed the earth.

“If you think today’s cockroaches are scary, just imagine a flying one about a foot long,” Naranjo said. “The oxygen levels were so high during that period that everything was substantially bigger. Some of the dragonflies were the size of eagles, and centipedes the size of dogs.”

Even though the prehistoric insects on display at the museum are just models, they can still be pretty intimidating. “These are replicas of ones that are in the Smithsonian,” Naranjo said. “They’re scary but were fun to make.”

Many of the specimens in the museum were discovered with their teeth still intact, showing just how dangerous they were for anything that got in their way.

The woolly mammoth in the museum’s collection is part of an extinct group that survived until about 10,000 years ago. It had a thick layer of fur that helped it survive the ice age. It lived alongside early humans and became extinct, probably due to climate change and hunting by humans. It grew to be the size of modern-day elephants and is most closely related to the Asian elephant.

A mammoth had four large molars that it would use to grind its food, mainly grass and other vegetation. These molars could be replaced by the animal up to six times in its lifetime.

A Smilodon, perhaps better known as a saber-toothed tiger, is also on display. Smilodons lived during the ice age and became extinct about 10,000 years ago, along with the woolly mammoth. The Smilodon hunted large animals, such as bison and camels. Scientists believe that the loss of a food source could have been a factor in its extinction.

Prehistoric animals aren’t the only thing that draws crowds to the museum. The Gem Room at the Naranjo houses a collection of precious stones, money and jewelry that Naranjo has collected over the years.

Confederate currency was printed just before the outbreak of the Civil War. After the Confederacy lost the war, the money was worthless, but it is still a collector’s item for some history enthusiasts and antiques dealers. An 18-karat gold necklace once owned by British writer Rudyard Kipling is another prized item in the Gem Room.

These terra cotta water jugs were unearthed in the Holy Land and date to the time of Moses. They are fully intact and more than 5,000 years later still hold water.

The collection of pottery and coins from thousands of years ago are remarkably intact. Coins that were used during the time of Jesus are displayed inches from visitors, as are water jugs from the time of Moses.

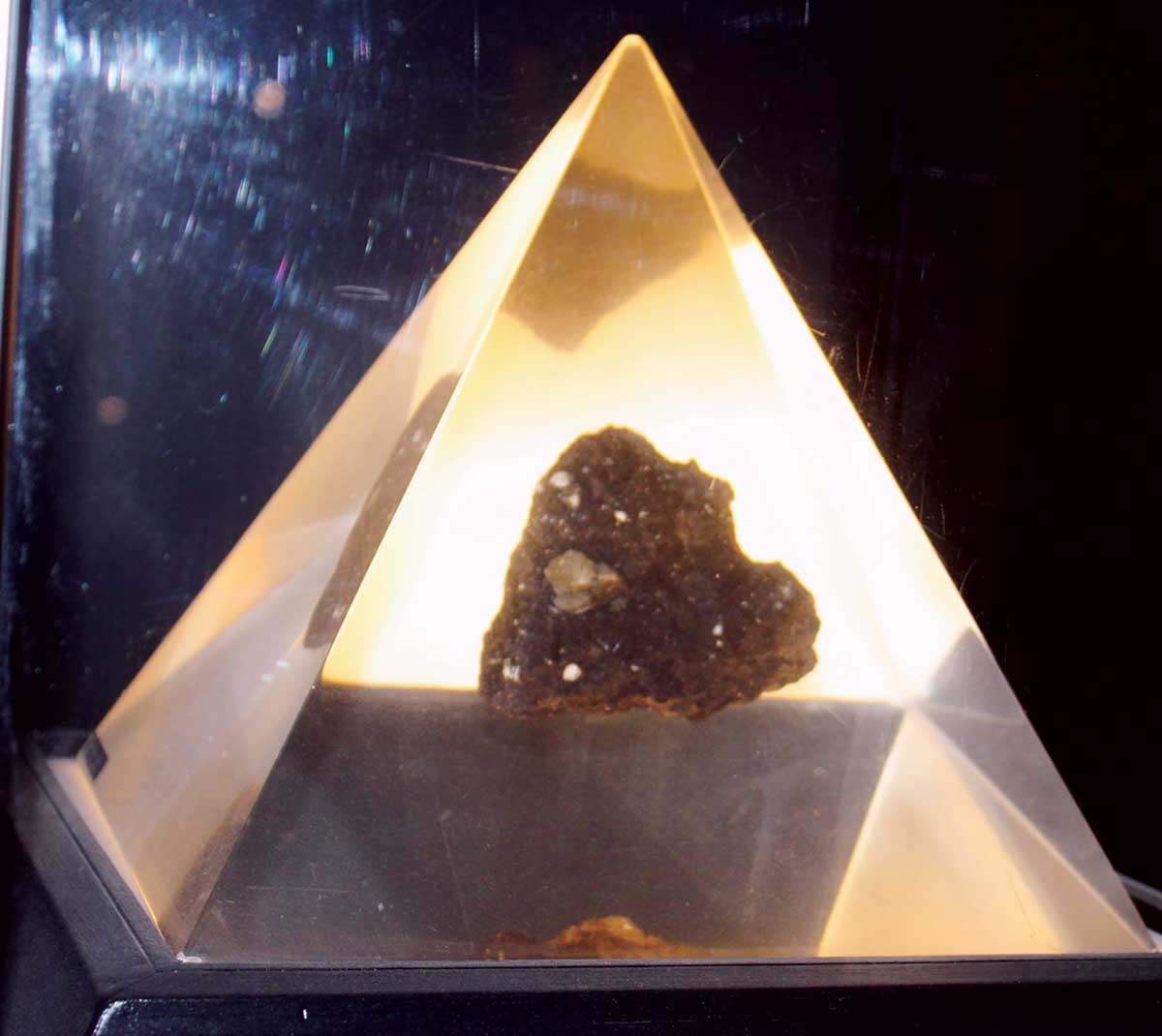

Bringing vistors into the present—and perhaps offering them a glimpse of the future—is an exhibit from NASA, which includes the largest moon rocks brought back by the crew of the Apollo 14 mission. There is also a replica of the Mars rover, along with vehicle tires and a spacesuit that have done duty in space and a photo gallery dedicated to the East Texans who helped retrieve pieces of the doomed space shuttle Columbia, which exploded upon reentry into the atmosphere over East Texas.

This moon rock, brought back by the Apollo 14 crew, is the largest piece to have returned from that mission.

The museum encourages teachers to bring their students. “Field trips are a great way to encourage students to study the world around them and allow children to interact with what they are learning in the classroom,” Naranjo said. “When we built the museum, we wanted to provide a place for the students of East Texas to learn about science and natural history that was closer and more accessible.”

The museum is located at 5104 S. First St. (Highway 59 South) in Lufkin. It is open 10 a.m.–6 p.m. Mondays–Saturdays and 1–6 p.m. Sundays. Admission is $7.50 for adults, $5 for children 4–18 and free for children under 3. For more information, call (936) 639-3466 or email [email protected].