Years ago Scooter Cheatham asked a classroom of high school sophomores to figure out how plants play a role in everything around them. As an example, he challenged them to connect plants to a pair of scissors. The Austin students, hoping for an easy answer, contacted the manufacturer. “There are no plants in our scissors,” a representative emailed back.

The response forced the teens to do their research. Ultimately “they learned that the manufacturing of steel to make scissors requires coal,” Cheatham says. “The orange plastic handles are derived from petrochemicals. The students also realized that the company representative was as ‘plant blind’ as everyone else about the importance of plants in our lives.”

They matter so much, in fact, that Cheatham has made them his lifelong mission. Plants support our food, health and industry—even contributing to the formation of coal and petrochemicals. For more than 50 years, he and his collaborators have worked to compile the ultimate reference encyclopedia: The Useful Wild Plants of Texas, the Southeastern and Southwestern United States, the Southern Plains, and Northern Mexico.

Since 1995, Cheatham’s nonprofit Useful Wild Plants has published four volumes, each counting 600 or more pages and collectively weighing nearly 20 pounds. When completed, the set will include at least 20 volumes and document the economic uses of more than 4,000 plant species, both native and naturalized.

“There’s nothing else like our volumes in the world,” says Cheatham, seated at UWP’s office in East Austin. “They’re the most comprehensive, interdisciplinary treatment of plant species ever done, going back to their prehistoric uses and forward to the most recent chemistry.

“People ask if this is our passion,” adds the self-educated botanist. “I say it’s our obligation to the planet. We’ve got to do this, or we won’t be ready when we run out of oil and gas. The smallest single plant on our planet has more promise for our future than anything we could study in outer space.”

Whenever his time allows, Cheatham, an architect and community and regional planner by profession, returns to Cuero, where he grew up gardening, milking cows and riding horses. As a boy, he explored and hunted on his grandmother’s nearby ranch along the Guadalupe River, a portion of which he owns today. Back then, he didn’t pay much attention to the live oaks, native grasses and other plants.

The sweet, slightly tart berries of an agarita, an evergreen shrub with many medicinal uses, can be made into wine and coffee.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

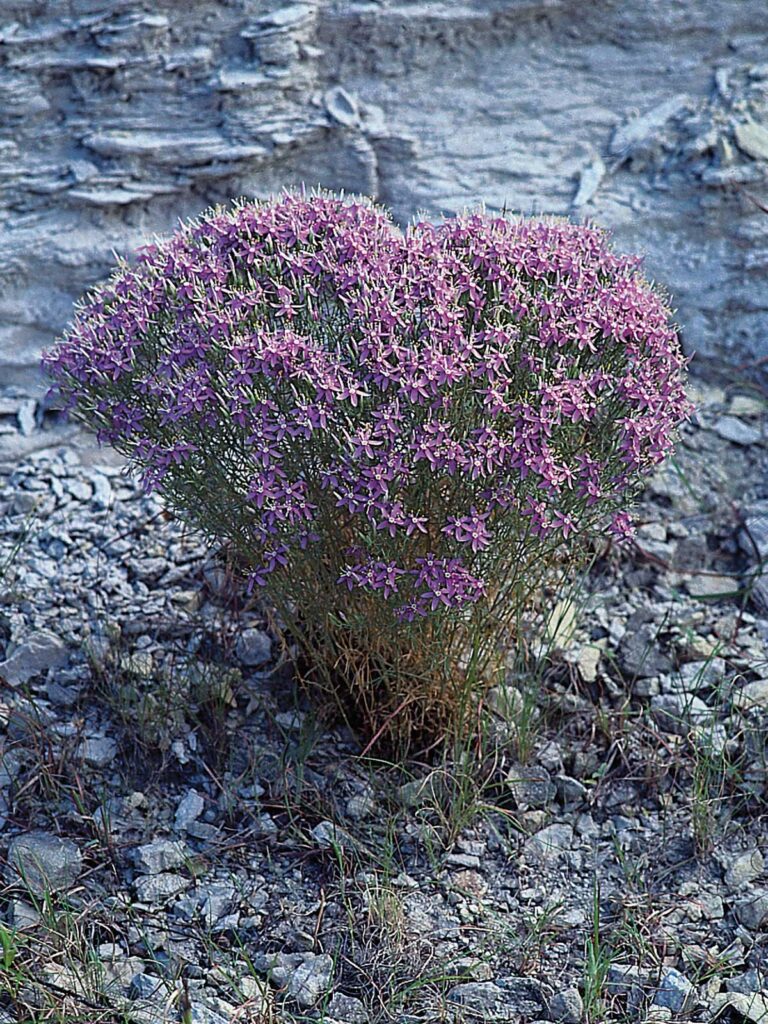

Mountain pink is a great plant for rock gardens.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

A honey-scented agarita in bloom.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

That was, until 1971, when he and a pal, both students at the University of Texas, embarked on an “experimental” archaeology project. During spring break, they lived off Cheatham’s family land like Indigenous peoples once did, using tools they’d made themselves. The experience profoundly impacted Cheatham.

“For 10 days, all we ate was a possum and an armadillo,” he recalls. “Out there, we were surrounded by plants. But I knew only a few common ones, like pecans and dewberries. That’s when I realized how much we rely on plants.”

The lightbulb moment inspired a yearning to learn more about the value of flora. Back on campus, Cheatham visited botanist Marshall Johnston, who the year before had co-written and published the 1,881-page Manual of Vascular Plants of Texas. Cheatham asked the professor if there was a comprehensive resource on the usefulness of plants.

“No,” Johnston told the younger man. “You should do it.”

So in 1971, at age 26, Cheatham began what would turn into a monumental, decadeslong undertaking.

Alongside the project, Cheatham, an accomplished artist and photographer, taught architecture and watercolor classes at UT for 10 years. He also led classes that taught students how to forage for wild edibles.

In 1977, a recent UT anthropology graduate named Lynn Marshall signed up for the foraging class and agreed to pay for half her course fees by volunteering with UWP.

She never left. Like Cheatham, she has dedicated herself to the endeavor.

At the project’s start, compiling just the species list and project parameters took a year and a half. Then Cheatham and Johnston traveled extensively, photographing plants in various stages of life. Filing cabinets in UWP’s office contain their 350,000 slides. More filing cabinets house thousands of manila folders, each labeled by plant genus and packed with notes, printouts and research.

The drought-hardy damianita boasts aromatic blooms in spring and summer.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

Prairie paintbrush blossoms attract hummingbirds and bees.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

A Texas redbud’s young seedpods are edible.

Courtesy Useful Wild Plants

In 1995, Cheatham; Johnston, who has since retired; and Marshall published their first volume. Subsequent volumes followed in 2000, 2009 and 2015. They may be ordered through the UWP website at usefulwildplants.org.

The tomes are made to last. “We believe people will need them for several hundred years,” Cheatham says. “So we don’t use cheap paper that would turn yellow in 18 months.”

Altogether, the four volumes published so far document 833 species. Organized alphabetically by genus, Volume 1 begins with Abronia (sand verbenas) and ends with Arundo (giant cane). Volume 4 covers Cenchrus (grassburs) through Convolvulus (wild morning glories). Still in progress, Volume 5 will begin with Conyza (horseweed).

Each genus section includes species descriptions, range maps and color images. Subheadings enable readers to quickly find specific information, such as “Native American food uses,” “chemical components” and “author dye tests.”

Entries run from less than one page to dozens. For example, Bowlesia (Bowles parsley) is a scant page, but Carex (sedges)—the largest genus in Texas flora—fills 76 pages.

Most people know about grassburs. When stepped on, their spiny seedheads hurt like the blazes to pull out—hence their reputation as a detestable weed. But surprise: “Some members of the genus Centhrus are highly valued as range grasses that increase the lease value of grazing lands,” according to The Useful Wild Plants of Texas. “Native Americans of the Southwest and prehistoric people of Texas used Centhrus for food, therapy and utilitarian purposes.”

With more than a dozen volumes and thousands of entries still to publish, Cheatham hopes to recruit and train more staff.

“Lynn and I are spread extremely thin,” he says. “Right now, we’re in a phase to raise consciousness about the importance of plants and publicize what we’re doing so we can raise the funds necessary to build a team that will finish this project. With a full staff, all the volumes could be completed in seven years.

“People need to know about Useful Wild Plants so they’ll carry it on after we’re gone,” he says. “This project belongs to the world.”