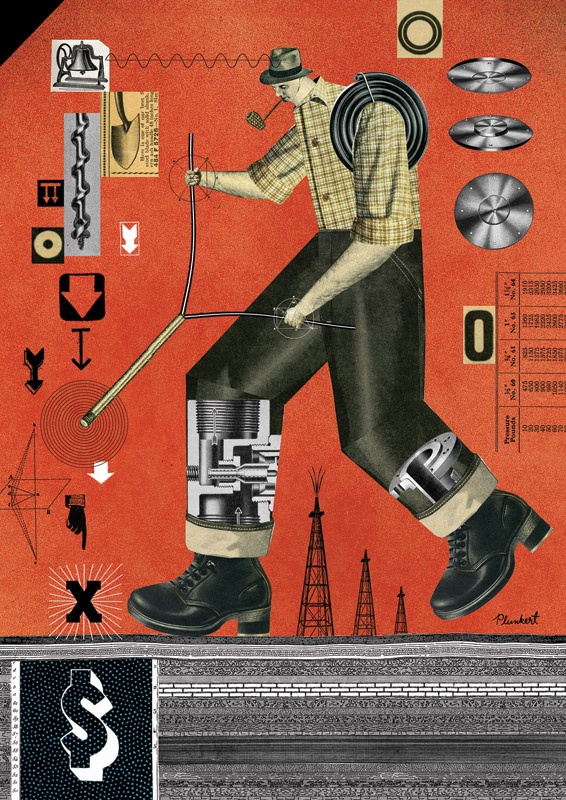

A Travis County farmer named Charles Rolff devised an apparatus in the 1930s he called a doodlebug machine, which he believed would locate large underground deposits of oil. “It was described as a secret tube, sealed at both ends,” United Press International wrote. “At one end, there was an opening to insert a 15-inch fork with two handles. In operation, a man takes the fork in both hands with the tube up and holds it over the land or leases, and by some way he can tell whether the land has oil-bearing possibilities or whether it’s dry.”

The doodlebug worked on generally the same principles as a divining rod that dowsers used to find water. Only certain people were believed to have the gift of sensing water or other deposits through the devices.

Rolff and a group of investors sued the Pearl Oil Company for proceeds and royalties in 1935, claiming the company used his doodlebug to find oil in Rusk County. A Williamson County jury decided that the presence of a doodlebug was irrelevant.

The jury didn’t say the doodlebug didn’t work, just that it didn’t matter.

An appeals court ruled against Rolff. In his written opinion, James McClendon, chief justice of the Court of Civil Appeals, said, “We take judicial knowledge of the scientific fact that there is no virtue whatever in the ‘doodle bug’ in locating oil or other substances underneath the earth.”

David Plunkert

In the early days of oil exploration, a doodlebug or divining rod made as much sense to some people as geology or seismology. In establishing the rule of capture as the water law of the land, the Texas Supreme Court in 1904 had deemed that underground water is too “secret, occult and concealed” to regulate. If the capricious behavior of underground water smacked of mysticism, so did underground oil.

Around the same time Rolff was promoting his doodlebug, two men, Ralph Malone and Vivian Buie, were hawking a gadget that operated on the same mysterious principles. In 1935 Malone and Buie found themselves in court, charged with swindling Houston investors out of $20,000. Buie was sentenced to five years for mail fraud. Malone got three years.

Lawyers Arthur Heemann and C. Ray Smith not only lost the case for Malone and Buie but also ended up as defendants on mail fraud charges. They hired their own lawyers who argued the two men were not swindlers, even though Heemann had been charged five years earlier for promoting a bogus outfit called the Oil Investors Company. Heemann and Smith were acquitted.

By the late 1940s, the Securities and Exchange Commission was investigating Malone for hawking a device he called a magnetic logger. The SEC concluded: “The claims made for its efficacy in discovering oil were the usual ones and were false.” A 1951 injunction put an end, once and for all, to Malone’s shenanigans.

But oil field fraudsters changed with the times. When America became fascinated with UFOs, Silas Newton and Leo GeBauer claimed to have a machine that “operated on the same magnetic principles as the flying saucers.”

They said they came across a device after an alleged spaceship crashed in Aztec, New Mexico, in 1948. Newton and GeBauer convinced author Frank Scully they were telling the truth, so he published a book called Behind the Flying Saucers in 1950 that sold 60,000 copies. True magazine checked out the book’s claims in 1952 and deduced that Newton and GeBauer were “oil con artists who had hoaxed a gullible Scully.”

A jury agreed. A headline in the The Denver Post announced the verdict: “ ‘Saucer Scientist’ in $50,000 Fraud.” Their UFO-inspired oil-finding machine turned out to be a box of radio parts with a bunch of cool-looking dials and switches.

In 1936 the Society of Exploration Geophysicists warned young geophysicists about employing “black magic” or “doodle-bug” methods based on unproven properties of oil, minerals or geological formations.

However, in the 1982 book Geophysics in the Affairs of Man, the authors noted that the term doodlebugger had taken on a new meaning by the 1950s.

“Twenty years later, it was a badge of honor to be known as a doodlebugger, i.e., the field personnel of geophysical crews,” they wrote. “Still later, the term was applied to everyone who worked in exploration geophysics.”

Clay Coppedge, a member of Bartlett EC, lives near Walburg.