Gayland Sorrells climbs aboard a big, oddly shaped yellow machine and pushes a button. The machine rumbles to life, its front attachment looking more like the pinchers of a gigantic, angular beetle than an invaluable piece of pecan-picking equipment. This machine is, in fact, a significant part of harvesting the Lone Star State’s favorite nut, a product that Gayland and his father, Kinley Sorrells, have been tending for three decades.

“Go ’head,” Kinley Sorrells says, urging his son to continue the starting-up process. “Fire her up.”

With the push of another button, hydraulic action forces the pinchers to separate. With the press of yet another button, they come together, the better to clamp on to a tree trunk and shake the living daylights out of it. Ripe pecans rain down. California-based Orchard Machinery Corporation claims to be the only company in the country that makes the Shock Wave Mono Boom, a wickedly efficient piece of equipment that helps the Sorrells harvest their crop. This is a far cry from the Depression years when pecan thrashing was done by hand.

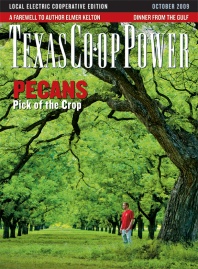

Every fall, during harvest season, a variation on a theme of the same scene is repeated throughout Comanche County, home to 10,000 acres of managed, or farmed, pecan trees—the state tree of Texas.

Once the shaker forces branches to release their fruit, another piece of machinery sweeps the pecans into rows, and a tractor-pulled harvester—complete with rotating rubber and wire fingers—gathers the pecans. After a vacuum fan blows out the trash, such as leaves and twigs, the pecans are carried by conveyor belt into a harvesting trailer and then hauled to a cleaning plant. Pecans consist of about 25 percent moisture when they’re shaken from trees; ideally, that number should drop to 4 percent during the drying process.

With a growing season that lasts from six to seven months and an average annual rainfall of 30 inches, Comanche County farmers produce a variety of agricultural products, including pecan, grain, hay, watermelon, cantaloupe and peanut crops. In 2008, the sales of dairy cattle and their milk, beef cattle, sheep and goats accounted for 86 percent of the county’s $143 million total cash receipts for agricultural commodities, with crops accounting for the remainder. Pecans, which typically produce about $5 million in annual sales, generated $2.7 million in a down year in 2008.

Sorrells Farms is one of the county’s farms that contributes a variety of agricultural products. Thirty miles southwest of Stephenville and five miles east of Comanche, just a quarter-mile past the point where blacktop gives way to a well-traveled dirt road, the farm is home to a 30-year-old family business that also includes cattle, hay, watermelons, cantaloupes, squash, zucchini, jalapeños, onions, peaches and tomatoes.

But it’s pecans where the farm really makes its mark, and patriarch Kinley Sorrells has been watering, feeding, harvesting and selling them since completing undergraduate and graduate studies in agricultural education and soil science at Tarleton State University in Stephenville. Gayland followed in his father’s tracks with a degree in agricultural economics.

Together, father and son tend their 1,200 acres. With 48 trees per acre, it is an exercise in continual vigilance. During the growing season, from April through October, the trees require one to two inches of water per week from rain and/or irrigation. One acre-inch of water, which would cover an acre of ground an inch deep, equals 27,154 gallons.

When the Sorrells aren’t irrigating, praying for rain to start or praying for it to stop (which hasn’t happened lately), they’re on the lookout for raccoons, deer, opossums and, of course, squirrels that can make short work of a crop if not strongly discouraged. Here and there are massive ruts where wild pigs rooting up the ground in search of food have made their presence known.

“When we’re not getting after the wild pigs, we’re on the lookout for the other pests—bugs and disease,” Kinley Sorrells says as he navigates corridors of trees in his dusty four-wheel-drive Ford pickup. In addition to guarding against such diseases as pecan scab, stem end blight, fungal leaf scorch and powdery mildew, farmers must also look out for aphids, stink bugs and the dreaded pecan nut casebearer, a moth whose larvae tunnel into pecan nuts.

“You really have to look out for casebearers,” Sorrells says. “They grow into moths and can really do you in. The adults come up out of the ground, get into the trees and deposit eggs on the tip of the nuts. They know just when the tree is pollinated. That’s when they hatch. Larvae burrow into the young fruit. They can destroy a whole cluster, so we have to spray at just the right time.”

The right time to spray pesticides, Sorrells says, is when casebearers start arriving on the scene and are lured into pheromone traps. The traps contain the female moth’s pheromone—the chemical she releases to attract the male moth—and snag the moths with a sticky, glue-like substance on the bottom. Coordinating spraying with the use of the traps lowers the use and cost of pesticides, he says.

Under Environmental Protection Agency regulations, pesticide sprays used in pecan orchards must pass registration requirement testing—for example, no pesticide residue may be found in pecan kernels—before they can be sold in the United States.

As he crisscrosses his orchard in his dusty pickup, Sorrells stops in a stand of trees, picking a pecan and slicing away a horizontal cross section to demonstrate the maturation process that will in time yield a fully formed pecan. The varieties that he grows include Cheyenne, Kiowa, Wichita, Pawnee, Mahan, Cape Fear and Kanza.

“Pecan growing has had its ups and down what with the fluctuating price of pecans, but things had been on an upswing until the economy tanked this year; then we had the same problems everybody else had,” he says. “The problem we’re facing this year, actually the past two years, has been the increase in fuel costs, and it hit us hard. Chemicals and fertilizers are tied to oil as well, so we’ve had increased costs.”

Pecans grow wild only in the United States and Mexico. Here in Texas, where pecans are grown in roughly 200 counties from the Panhandle to the Rio Grande Valley, the nuts are the state’s most important native horticultural crop, according to John Begnaud, a retired extension horticulture specialist with Texas A&M University’s AgriLife Extension Service.

The United States and Mexico remain the world’s largest exporters of pecans, with Texas ranking second only to Georgia in U.S. production. Sorrells sells locally, statewide, nationally and internationally, with mainland China, Hong Kong and Mexico as customers. Pecans as a cash crop have spread to 30 countries as far away as Australia, China, India, Israel and South Africa.

Because pecans are such a viable crop, there are active breeding programs to improve pest resistance, prevent disease and encourage early maturation to accommodate various growing zones. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Agricultural Research Service, oversees a high-profile pecan genetics and breeding program in College Station.

Despite their broad appeal, many in this country still think of pecans and pecan products as a seasonal treat for Thanksgiving or Christmas. Fortunately, we Texans know better.

——————–

For more information about Sorrells Farms, which is served by Comanche Electric Cooperative, call (254) 879-4677, go to www.sorrellsfarms.com.

Ellen Sweets, who wrote about Austin chef Hoover Alexander in the March issue of Texas Co-op Power, is a former food and feature writer for The Denver Post.