Learning to drive is a rite of passage for most ranch kids. We drive before we’re old enough to carry a driver’s license, before we can even reach the gas pedal. We learn by trial and error. It’s a bonding experience—and free child labor—for many families.

I started driving from my dad’s knee when I was about 3, and by second grade, I was steering solo in low gear while he shoveled out cottonseed from the bed of the truck.

I learned on a stick shift, gripping the wheel as my dad yelled from the passenger seat or my mom watched through split fingers over her eyes. Driving a standard transmission is a two-legged job. You need two legs, two hands—“at 10 and 2,” as Dad always reminded me—and at least four eyes to watch for a cow or deer that may decide to wander into the road in front of you.

Starting out with a standard is not as easy as an automatic. There’s a certain finesse that comes with hours of practice—and a lot of engine stalls.

My mom was definitely the more patient of my parents, but she had such fond memories of her father teaching her and her two sisters how to drive on their ranch that she felt that was how it should be for me and my sister with our dad. My mom was a self-described “Daddy’s girl,” and every time she heard Alan Jackson’s Drive (For Daddy Gene) on the radio, her eyes teared up. Drive came out around the time my grandpa entered an Alzheimer’s care facility. He could no longer remember those summers he let his three girls steer through the pastures for hours, giggling as he grinned back at them over his horn-rimmed glasses.

So she left the driving lessons to Dad.

I had my first crash at age 8. Dad was trying to get some cattle to go through a gate, but the ’76 Chevy my sister and I sat in was too close, so he hollered to me to back it up a bit.

“But I haven’t learned how to back up yet,” I yelled.

“Just put it in reverse,” he shouted with eyes that added “—common sense.”

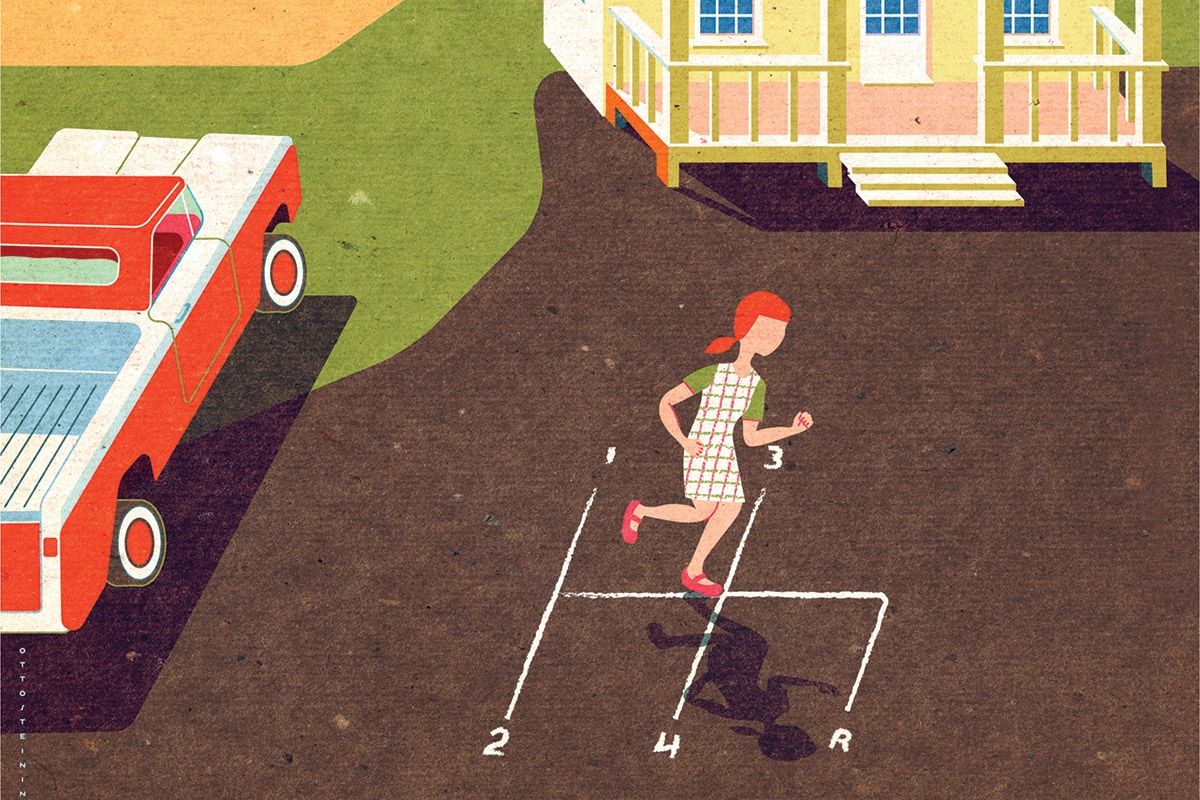

“Ooookay,” I thought, “this shouldn’t be too hard. Just put it in reverse. Reverse. R. Over to the right and down.”

I was so focused on remembering “R” that I forgot to push in the clutch before turning the key. When you forget to push in the clutch, your truck leaps forward really fast. And your life flashes before you. All 8 years. We headed straight for a corner fence post. The cows leapt to get out of our way. My younger sister was crying and yanked at her seat belt to get it buckled before we wrecked. We went through part of a fence and over some mesquite trees before ramming into the post with a loud thud.

That thud felt like my last heartbeat. It was followed by total silence. When I finally mustered up the courage to peer over the steering wheel, thinking since the crash didn’t kill me, my father would, I was shocked to see Dad laughing. The trial-and-error method of teaching had backfired.

All the trucks we drove on the ranch had personalities of their own. They had names like Goldie, Crew Cab and Sammy. All of them very old. We needed hardy vehicles that could climb rocky hills, traverse muddy draws and take being slapped around by thorny mesquites all day. Most didn’t have a working air conditioner, so we rolled the windows down to smell the countryside. If you hit the seats too hard, dust clouded around you. Duct tape patched a cracked dashboard, and headliners sagged with age. We had grill guards to protect us from deer, headache racks to hold our gear.

When we got older, my sister and I started taking turns driving home from the mailbox—about 20 minutes down the road—where the bus dropped us off in the afternoons. Our rule still stands today: Shotgun gets the gate!

Dad made me learn how to change a flat and check my oil before I could get my driver’s license. To this day, if I get a flat, I don’t need to call a man to come save me. By gosh, I can fix it myself. My husband thinks that’s pretty cute, too.

Why was learning how to drive so important to me as a kid? It was the freedom it promised. I knew that if I could drive, I could arrive anywhere. This narrow dusty road connected our ranch house to the highway that led to interstates and metropolises, beaches and mountains. This road led to friends’ houses, to all the parties we would go to, to all the dates we would have. These roads led to a world of possibilities.

Now, I choose to drive in the opposite direction down these caliche roads. Back to the ranch. Back to where it all began.

Brenda Kissko is a native Texan who writes about nature, travel and our relationship with land. Visit her online at brendakissko.com.