After the Civil War ended, Union Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday landed in Galveston in 1866 to command federal forces in that important Texas city. He surely didn’t think that his mission would lead him to one day being wrongly credited with inventing the game of baseball.

A baseball game during recess at a San Augustine grade school, photographed in 1939 by Russell Lee for the Farm Security Administration.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Two decades earlier, a New York sports enthusiast named Alexander Joy Cartwright invented the game by writing new rules for the old English game of rounders, thus formalizing the basics of modern baseball. Doubleday, like many Civil War leaders on both sides, endorsed “base ball” (originally spelled as two words) as a way for troops to exercise and build morale.

On April 11, 1861, a Houston newspaper announced the formation of Texas’ first team, the Houston Base Ball Club. Players who joined the club were asked to meet at an open field in town at 5 a.m. three days a week, weather permitting, for “field exercise,” The Weekly Telegraph wrote.

The day after this newspaper account, Confederate troops bombarded Union forces at Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina. The war was on, and the effort to start baseball teams ceased. At prisoner-of-war camps during the war, however, Union troops taught the game to captured Confederate soldiers.

After the war, those Confederates brought the game home to Texas and other Southern states. A few games might have been played during the war, pitting Union against Confederate troops, but the first baseball diamond in Texas was drawn on Galveston Island’s east end, according to the Galveston Historical Foundation.

Bats and balls take a different shape at the 2008 Texas Forts Trail Vintage Base Ball Tournament.

Randy Mallory

That’s where the newly formed Galveston Base Ball Club held its first game, in early 1867. A year later, The Daily Telegraph reported the first intercity game in Texas. The Galveston Robert E. Lees took on the Houston Stonewalls (both named for Confederate generals) at the San Jacinto Battleground near Houston.

The April 21 game was part of the state’s annual celebration of Texas’ 1836 victory over Mexico and was later described in a 1940s book sponsored by the Harris County Historical Society.

A 1939 night baseball game in Marshall, photographed by Russell Lee for the Farm Security Administration.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

The teams traveled by boat to the battleground turned ballfield. The Stonewalls left their Houston dock after a rousing send-off complete with German band music and a few San Jacinto battle veterans aboard. The team wore “showy uniforms consisting of red caps, white flannel shirts and black pants,” The Daily Telegraph reported. Their boat also pulled a barge suitable for celebratory dancing, an act that proved providential as the Stonewalls romped the Lees, 34-5.

Sandlot Revolution

Baseball’s early players were amateur members of local clubs, competing mainly for exercise and camaraderie. Today’s top players are professionals, of course, vying for fame and fortune. Yet that original spirit of camaraderie—tempered by a healthy dose of competition—remains alive and well for those who play an increasingly popular version of the sport: sandlot baseball.

Hal Rochkind, who runs an insurance agency on Galveston Island, is one such player. Wearing No. 14, Rochkind plays second base for a 10-year-old sandlot team called the Gulf Coast Sugar. Its players are baseball lovers of various ages from Galveston and Houston. Like many sandlot teams, the Sugar play only a few games a year. Team members do have families and day jobs, after all.

Camaraderie is key for the Gulf Coast Sugar, a sandlot team made up of players of varying ages from Houston and Galveston.

Jessica Wochner

They play at a city park not far down the island from that first Texas ballfield. They also play on fields of varying quality at away games and the occasional tournament.

“We all grew up playing baseball as kids, some in Little League and some even in high school or college. Most of us grew up following the Astros,” Rochkind explains. “Sandlot is a way we hold on to our baseball memories while enjoying a healthy activity out of doors. We bring our families to watch the games so maybe they’ll keep the tradition alive.”

Gameplay at the home field of the Gulf Coast Sugar on Galveston Island regularly stops to let kids run the bases and, during this game at Halloween, to collect candy.

Jessica Wochner

The Texas sandlot revolution began to take off in 2006 after architect and baseball fan Jack Sanders and friends formed a team in Austin called the Texas Playboys, named after Texas music legend Bob Wills’ Western swing band. They challenged friends in Austin and other cities to form pickup teams to play the game they loved.

After several years of rising interest in sandlot, Sanders built a field just east of Austin called the Long Time. His 5-acre field of dreams hosts games played against a family-friendly backdrop of Austin-style live music and beer. The games are generally played on the second Saturday of the month from March to October.

The sandlot phenomenon remains a relatively unorganized loose-knit group of teams that play largely by standard hardball rules. The goal is to keep play flowing in a fun-loving way without runaway scoring or injuries.

Home-field rules, for example, stipulate that if a player hits a home run, then that player should bat from the other side of the plate on his or her next at-bat. If a team hits five homers, each additional homer is ruled an out and everyone gets a chance to hit. Pitchers may wear a cowboy hat if they so choose.

Players of the Memorial Moonshots and the Gulf Coast Sugar celebrate during a sandlot baseball game.

Jessica Wochner

Fans spread out on picnic blankets eating barbecue as a horse watches beyond the left field fence. Fun overrides winning, but a sign at the Long Time still warns onlookers that “foul balls are real.”

Over the past decade or so, other sandlot teams have formed across Texas and beyond to join in on the fun. In addition to the Gulf Coast Sugar, other Southeast Texas sandlot teams include the Houston Buffs, Memorial Moonshots, Houston Gamblers, Space City Baseball Club and the Texas Oil Dawgs. Several of those teams play at the Long Time on May 14.

The Memorial Moonshots and the Gulf Coast Sugar play a sandlot game on Galveston Island.

Jessica Wochner

The newly formed Texas Oil Dawgs generally follow Long Time home rules, says Houston photographer Mark Champion, the team’s manager and a player. “We have players 50 years or older, so if former college players show up, we ask them to tone it down,” Champion says. “We don’t want anyone to get hurt. Fun is the name of the game.”

Vintage Baseball

Another small group of baseball aficionados play by even older rules and jargon that differ delightfully from the modern game. Vintage baseball, as it’s known, calls for original 1860s rules. Players wear period uniforms and use vintage-style bats and balls. You make an out by catching the apple (ball) on the fly or after one bounce—a pain-saving rule for ballists (players) who play without gloves. Hurlers (pitchers) throw underhanded from 45 feet away, and the Blind Tom (umpire) calls no balls or strikes—though he may do so if the striker (hitter) unduly delays the game.

There’s no sliding into base—that’s too undignified for the 1860s. Nor can one overrun first base (though that rule is sometimes overruled out of concern for older, less agile ballists). A welcome rule change allows a fielder to put a runner out by tagging him rather than “plugging” (hitting) the runner with a thrown ball, as was once common.

The number of vintage baseball teams has dwindled in the past few years. A remaining Dallas-area team, the Farmers Branch Mustangs, still plays a few games a year at Farmers Branch Historical Park, including two upcoming spring demonstration games April 2 and May 7. San Angelo’s historic Fort Concho hosts occasional games, including one December 3 at the early Texas frontier fort, which was deactivated in the late 1880s.

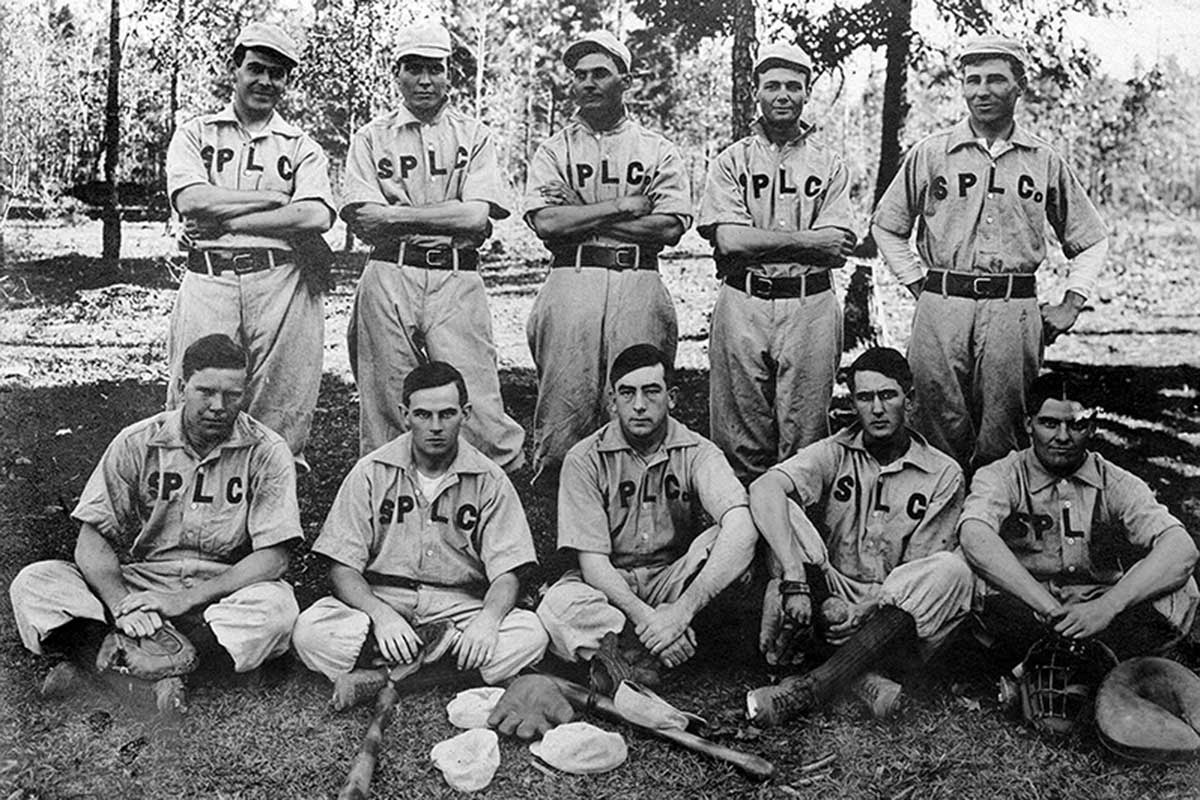

The Southern Pine Lumber Co. baseball team of the Diboll Athletic Society gather on the baseball grounds in November 1907. According to the January 18, 1908, edition of American Lumberman, the athletic society was created by the company for young men with “semiexecutive positions such as office work and the various positions that are given out to young men of quality.”

Photo courtesy the History Center in Diboll

About the same time West Texas forts like Fort Concho were closing, baseball activity was heating up across the state. Almost every town had an amateur ball club, sometimes sponsored by a local industry, such as a sawmill or oil company.

As baseball was spreading like wildfire, some promoters saw the chance for profit. The Texas League formed in 1888 as the state’s first professional baseball league and held its first game between the Houston Babies and the Galveston Giants. The era of rapid industrialization saw many farm families moving into towns for jobs that brought disposable income that allowed leisure time for watching minor league games. The Texas League lasted off and on until 2020, when it became part of Major League Baseball’s Double-A Central.

The Longview Cannibals baseball team in 1903.

Photo courtesy Longview Public Library

Even smaller towns could support semipro teams, such as those in the East Texas League of the early 1900s. Those teams bore names such as the Lufkin Lumbermen, Kilgore Drillers, Longview Cannibals, Nacogdoches Cogs, Rusk Governors, Texarkana Twins and the Jacksonville Tomato Pickers.

The East Texas League, like other minor leagues, survived the tough times of the Great Depression and World War II. But during the 1950s and 1960s, it was the easy times of modern life—brought about by TV and air-conditioning—that caused their demise. “East Texans turned on the window unit and plopped down in front of a television set,” writes historian Bill O’Neal in a study of the East Texas League in the East Texas Historical Journal.

The Port Arthur Sea Hawks’ 1915 opening game against the Beaumont Exporters. The stadium is located on the southwest corner of Orange Highway (16th Street) and Stadium Road.

Photo courtesy Port Arthur Public Library

The rise of youth baseball also reduced minor league attendance. “Parents who took kids to practice and games two to three times a week were less likely to attend a minor league game as well,” O’Neal writes.

A couple historical relics of the East Texas League still host baseball games—Tyler’s Mike Carter Field, built of red bricks during the Great Depression, and Kilgore’s Driller Field, built of oilfield pipes and boilerplate in 1947.

Family Game

Rochkind looks forward to another season of starting at second base for the Gulf Coast Sugar down on Galveston Island. He comes by his love of baseball naturally. As a board member of the Galveston Historical Foundation, he sees himself as part of baseball history. His father, Barry Rochkind, was a batboy for the Houston Astros, where he bumped into baseball greats such as Mickey Mantle and Ernie Banks. Later he called ballgames as a sports reporter for a local radio station and managed to get press passes for major league games in Houston.

“As a kid, I got to watch the games from the press box,” Rochkind says. “My dad put me into baseball, so he still comes to watch me play. I have two young boys, so it’s very special to have three generations together at the ballfield. That’s one way we can keep America’s pastime going.”