By 6 a.m., my roommate at quilt camp sits at her sewing machine, stitching some of the 1,272 tiny pieces of fabric that will become a twin-size quilt. Obsessive, yes, but our five days away from daily chores of cooking, cleaning and dog-walking free us—members of the Frontera Quilt Guild—to concentrate on quilt making. We have to make the best of this time.

This obsession, neither fattening nor illegal, brings the joy of creating useful, eye-catching quilts and results in gifts for family and friends, veterans, and children in foster care.

The John Newcombe Tennis Ranch in New Braunfels has hosted annual Frontera Quilt Guild retreats for 20 years, nearly since our guild was founded in Harlingen in 2000. In fact, the resort hosts 25–30 quilting and stitching groups like ours every year, providing the essentials—breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, ironing boards and large worktables.

The constant whir, hiss and “zzzzzt” of sewing machines provide the playlist. Creativity is limited only by our own imaginations and skills and driven by limitless fabric, design variations and advice from fellow quilters. I remind myself of a favorite saying: “There are no quilt police.”

Our 40-member guild, one of hundreds in Texas, includes a robotics engineer, a nurse, a grandmother and her grandchildren, retired educators, and Winter Texans. About half began quilting after being inspired by family members.

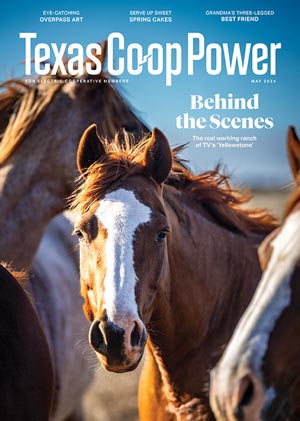

“My great-grandmother made quilts,” says Deb Carlile, a member of Magic Valley Electric Cooperative. “I always knew I wanted to make quilts.” Carlile taught herself to quilt from books, throwing away her first attempts. Now she fashions contemporary wall hangings and traditional quilts, drawing inspiration from TV shows like Yellowstone and instructional online videos.

But family tradition isn’t the only gateway. Dentist Nyla Gordon wandered into a quilt store 10 years ago and met the owner—“a woman with the most beatific smile,” she says. “I wanted to know what made her so happy.” Gordon signed up for a beginner quilting class.

At quilt camp, she hones her skills. “This is a vacation from a demanding job,” she says, flashing her own beatific smile as she pins yellow binding on a double wedding ring quilt.

While many quilters are retiring baby boomers who find they have time to immerse themselves in the time-consuming hobby, the craft attracts all ages. A.J. Simpson, 17 and wearing noise-canceling headphones, is at camp working on her first quilt. “Everybody’s helpful and supportive and not judgmental,” she says. Generosity identifies quilters as much as their clothing flecked with thread snippets.

Linda Villarreal says getting advice, seeing what other people create and fabric shopping are the camp’s big draws, along with “making quilts to give to people I love.”

Do you cherish memories of grandmothers and aunts gathered around a quilting frame? That’s sweet, but if our grandmothers had long-arm quilting machines, they would have used them.

The long-arm is one of the inventions that, beginning in the 1970s, modernized quilting, making the craft less tedious and more accessible. The rotary cutter (like a razor-sharp pizza cutter and better than scissors), the cutting mat and the long-arm—when combined with a boom in cotton fabrics, easier-to-use patterns and pre-cut materials—brought about a quilting renaissance.

Fabric and pattern designers and instructors became quilting’s rock star equivalents.

Those changes didn’t happen miraculously but came about because of determined women like Houston quilt shop owner Karey Bresenhan. She parlayed her store into what is now the International Quilt Festival in Houston—the nation’s largest quilt show—which will mark its 50th anniversary when it runs October 31–November 3 at the George R. Brown Convention Center.

Count me among the show’s 41,252 visitors last year, standing mesmerized by the fabrics, long-arm machines and countless accessories in the 635 booths. I’m also among the nearly 3,000 who attended some of the show’s hundreds of formal classes and lectures.

I heard quilt-maker and teacher Charlotte Angotti, known for her comical lectures, confess to stitching buttons over quilt block intersections to hide mismatched seams. Fourth-generation quilter Jenny K. Lyon gave practical tips on good lighting and sewing posture.

In addition, the show provides countless free demonstrations, mini workshops and the thrill of talking with quilting celebrities.

“Quilts are really the fabric of life. They tie us to the land,” says Cinde Ebeling, a member of Swisher Electric Cooperative who grew up sewing in Dimmitt, in the Texas Panhandle. “It was what you did.”

In 2014, during her treatment for breast cancer, Ebeling, a member of the Ogallala Quilters’ Society, created a chemo connection quilt. “I want people to think about the shock of diagnosis, treatment, hair loss, the heartaches and remissions,” she says. Some pieces of the quilt are the actual plastic bags that once held her chemotherapy pills, bringing you face-to-face with the scary reality of cancer and its effect on the patient and everyone around them.

After the Houston show, the Texas Quilt Museum in La Grange, between Austin and Houston, showcases some of the show’s prizewinning quilts through May, allowing many more people to discover and appreciate quilts as art. The museum’s changing exhibits include collections of antique, traditional, portrait and themed quilts.

Fostering the next generation of quilters, the museum offers storybook quilt time and, of course, runs a children’s quilt camp.