The kids show up for their riding sessions right on time. They strap on their helmets and calmly lead their horses from the cool shade of the barn into the hot, dusty arena at REACH Therapeutic Riding Center in McGregor, 20 miles southwest of Waco.

Twelve-year-old E.J. works on cinching a saddle strap. “Pull, pull, pull,” cheers side-walker Jesse Allen. E.J. grimaces with the effort as his horse, Jessie, a 22-year-old black-and-white paint, stands quiet and calm. With just a little more oomph, E.J. maneuvers the leather strap into the correct hole and breaks into a wide grin. “He couldn’t do that at all five months ago,” Allen says.

Offering health and mobility gains with the aid of horses is the mission of Larry Barnett, a retired U.S. Air Force pilot who became a therapeutic riding instructor in 2004. He founded REACH in 2007 to use equine therapy, or hippotherapy, to improve the physical and mental well-being of children and adults with special needs.

“This was his dream,” says Kristin Bolfing-Volcik, REACH executive director. “He went to a bunch of different riding centers to study what they did, and he had a lot of mentors from around Texas.” The result of that research and dedication is the REACH Therapeutic Riding Center, opened in 2008 and situated on 30 acres of pastureland donated by Gary and Diane Heavin, the founders of Curves International fitness studios. The REACH barn has stalls for 10 horses, an office, a viewing room, therapy room, tack room, wash stalls and wheelchair-accessible restrooms. The center has recreational use of the rest of the Heavins’ 400-acre property, which includes an extensive network of riding trails for therapeutic group rides.

Bolfing-Volcik, a Waco native and Heart of Texas Electric Cooperative member, started volunteering with the nonprofit organization in 2008 and went on to become certified by Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International as a therapeutic riding instructor. She helped the operation grow to its current size, serving 130 kids as young as 3 as well as adults and veterans of all ages. The center helps people with varying needs and disabilities, including those with muscular dystrophy and autism, trauma survivors, and patients in addiction recovery.

Greek physician Hippocrates was the first to write about the “healing rhythm” of riding horses in the fifth century B.C. In modern times, equine therapy was developed to treat soldiers wounded during World War I and came to the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s after a Danish rider disabled by polio won a silver medal for dressage riding in the 1952 Olympics.

Equine therapy is a tool rather than a profession. Licensed therapists—physical therapists, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists, for example—become certified by PATH International or the American Hippotherapy Association to use equine therapy as part of their practice.

According to PATH International, hippotherapy provides three-dimensional movement that mimics human walking. “You could work out every single day, and you’re still sore when you get off that horse because you’re moving all those different muscles,” Bolfing-Volcik says. The movement of the horse provides stimulation to the parts of the body involved in walking, provides a sense of rhythm and gait, and allows for more repetition per session than using machines in an office or gym setting. Performing regular barn chores and grooming can be healthy exercise for those building dexterity, balance or strength.

Horses are prey animals and are sensitive to the emotions of those in their herd, Bolfing-Volcik explains. This makes them an emotional mirror for humans working through anxiety, trauma, addiction or other emotional disturbances. Because horses don’t hide their emotions, people learn to identify and correct their own behaviors to further their relationship with the animal.

“If I have a hard day, I know I have to present to the horses in a calm manner,” says veteran Dalyse Mayo, brushing Jessie.

Julia Robinson

Horses also provide motivation for those who are otherwise bored, daunted or disengaged. “Some of these kids are in clinic a lot and they don’t want to do the work, but then they come out here and they’re riding a horse and they don’t even know they’re working,” Bolfing-Volcik says.

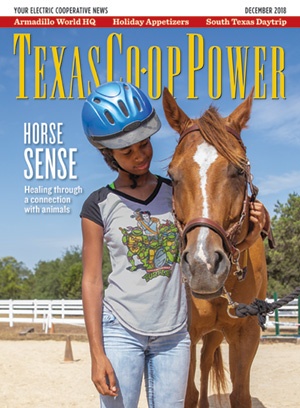

Brooklyn knows that feeling. The 12-year-old was diagnosed with cognitive and speech delays at a young age. “Every day, she went to school, went to her [speech] therapy and then came home. There was no excitement, and she fell into a rut,” explains her mother, LuCretia Denkins. School was a source of depression and struggle for Brooklyn, but she always loved horses. “She’s obsessed and wants me to buy her one,” Denkins says.

An insurance liaison discovered the REACH program and applied for Brooklyn to attend. She was approved for seven lessons last summer. “She has blossomed so much,” Denkins says. “It’s really amazing to see.”

Out in the arena, Brooklyn and the other students check their saddle girth and the length of their stirrups. Unlike E.J., Brooklyn has plenty of strength to tighten the straps. Her struggle is with memory. “If you tell her three things, she can remember one, maybe two,” Denkins says. “But with the horses, she has memorized everything. She knows what it really means to want to learn something.”

The students mount up from a mobility-assisted platform, the horses patiently waiting for the riders to find their stirrups. They warm up slowly, the side-walkers taking the reins as the kids circle their arms out to the side and make torso twists from the saddle. The movement of the horse adds a level of difficulty for kids who are building muscle and improving mobility.

After a few more exercises, the kids take the reins and lead the horses around cones and barrels and through a short maze made of poles on the ground. Then they perform a 360-degree turn inside a box marked on the dirt. An instructor gives directions and encouragement, but the kids are in charge of these animals more than 10 times their weight.

“There’s no words in the human vocabulary that can explain the emotional and spiritual experience going on between you and that 1,200-pound creature,” says Charity Martin, a barn assistant. “You are trying to trust, and it’s trying to build trust with you.”

Brooklyn, 12, maneuvers 20-year-old quarter horse Newt around the arena at REACH Therapeutic Riding Center in McGregor.

Julia Robinson

Allen agrees. He became involved with REACH as a participant in a post-traumatic stress disorder treatment program through the Waco office of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Allen was a firefighter and paramedic before joining the Army and experienced the effects of PTSD after his service ended.

“I came home from Afghanistan in 2010, and I didn’t care anymore,” Allen says. “Eight years of PTSD therapy, medication, groups, blah, blah, blah. … You’re never fixed, but this is the one thing that helped me the most.”

Allen was anxious on that first trip to the barn in the summer of 2017. “Horses can feel your energy,” he says, “so when you calm yourself down and then the horse calms down, it’s like looking at yourself in the mirror.” Allen kept coming back and developed a special bond with Kit, a paint with a large white blaze down his forehead. When his program ended, Allen asked to continue on as a volunteer, first with veterans, then with kids. Allen began enjoying life again, and other people saw it. “People said they had their old Jesse back,” he says. “My enthusiasm came back, and I’m back to helping people.”

Allen credits the staff but mostly the horses for his transformation. Now he gets to see the same transformation in those he helps. “We have kids in this barn right now who in the last five months have gone from little bratty little kids who are in their shells and shut down or no emotions at all to the sweetest, kindest, hardest-working little people,” Allen says.

Christopher, right, leads Stanley from the stable to the arena. REACH students learn to care for horses as well as ride them—grooming the animals and helping with chores around the stable.

Julia Robinson

Earlier this year, Allen took on a paid position as veteran program director and hosts Horses for Warriors, a Monday veterans-only program with unstructured riding time, optional group activities and a catered dinner. “The amount of good and help it does—people don’t realize,” he says. “I’m all about Western medicine as a paramedic. I’m not a naturopathic person, but this is an unused resource that can seriously help people out—kids and veterans.”

Near the end of Brooklyn’s session, the instructor tells the kids it’s time to trot. Brooklyn emits a small yelp and raises her arms with excitement. The students form a line at the end of the arena and one by one get their horses up to speed. The side-walkers jog along with them, and the kids beam as they bounce along in the rising dust.

At the end of class, they dismount, wiping the dust from their jeans and hands. Brooklyn pets the face of Newt, a 10-year-old quarter horse, and gives his cheek a scratch. It’s only been an hour, but the students walk taller and lighter than when they entered the arena. “I haven’t seen her that happy in a long time because school has beaten her down so much,” Denkins says. “She talks all about horses all the way home. She went from not talking at all to nonstop talking, and that’s amazing.”

Learn more about Julia Robinson at juliarobinsonphoto.com.