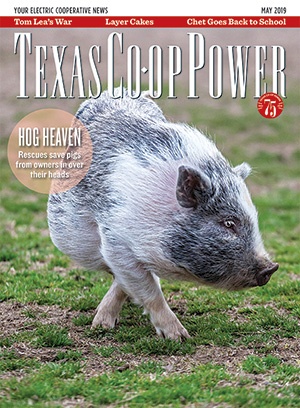

The stories always seem to start the same: with a precious photo and a short conversation. Melanie Bolling’s pet pig story began exactly that way.

“I saw a cute little piglet on Facebook, and I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I need one,’ ” she said of when she and her husband, Stephen, added weeks-old Pearl, a miniature potbellied pig, to their family in 2015. “It just kind of snowballed from there.”

Soon Bolling found an online community of Metroplex-area pet pig parents, many of whom were looking for new homes for their animals. Since the Bollings live on 10 acres in Wills Point, east of Dallas, she felt compelled to help. She took in three pigs in 2016 and another 30 in 2017. Then 90 in 2018.

That’s when Bolling realized most of the stories end the same way. Miniature pigs only start out that way, often outgrowing their owners’ lifestyles and expectations—sent instead to the wilds of the internet or worse. Miniature pigs, so named because they’re smaller than farm pigs, which can weigh up to 500–800 pounds, comprise more than a dozen breeds and can reach 200 pounds or more.

Experts estimate 90 percent of mini pig owners end up finding new homes for their pigs in their first two years. In response, dozens of rescues have cropped up across the state.

Web Extra: Melanie Bolling snuggles baby Holly at My Pig Filled Life.

Eric W. Pohl

The Bollings started one of them. My Pig Filled Life, powered by Trinity Valley Electric Cooperative, is home to more than 130 pigs across three barns. It’s a big commitment that’s only getting bigger.

“I could take in a hundred [pigs] today and not make a dent in the amount of calls,” Bolling said.

The Problem

Mitsy Wempe will be the first to tell you that she and her husband, Jason, made a mistake.

The two animal lovers were looking to share their 10-acre plot in Gilmer when they came across miniature pigs for sale in 2014.

“I saw the piglets, and I’m like ‘Oh my gosh.’ They were so stinkin’ adorable,” Wempe said. “As soon as my eyes laid upon them, I literally was hooked to the pigs.”

Mitsy Wempe interacts with P.J., one of the rescued pigs at Oinkin’ Oasis in Gilmer, which she operates with her husband, Jason.

Eric W. Pohl

They brought home Abigail first. Then many other pigs followed when friends and friends of friends realized the Wempes had space and were “the pig people,” she said. “So then it turned into, ‘Hey, I know somebody who has a pig and doesn’t want it anymore, do you want it?’ ”

Soon the Wempes had their first male pig. That’s when they slipped.

“We thought it would be interesting—fun, cool—to bring in an unneutered male and let him get my smallest pig pregnant because, of course, we were so ignorant,” Wempe said. “Because, you know, if you mate it with a small pig, you’ll have small pigs, right? Of course, that’s not how it works.”

Instead, unbeknownst to the Wempes, Magnus bred with four of their pigs, which led to 22 piglets in 30 days. He was neutered the next weekend, and the couple founded Oinkin’ Oasis, a sanctuary served by Upshur Rural EC that houses more than 90 pigs, which will live out their days there.

The Wempes weren’t the first to experiment with breeding, but they’re among the few to decline the easy money it can bring in. “It really opened our eyes to—we are the problem,” Wempe said. “That’s when we decided we were going to rescue.”

Since the 1980s, when Canadian farmer Keith Connell brought 19 straight-tailed potbellied pigs to the U.S. from Europe, untold thousands of breeders have taken a less noble path than the Wempes, breeding miniature pigs at runaway rates. Celebrities fueled a pet pig craze in the 2000s, when Tori Spelling, Denise Richards and Paris Hilton had reality TV shows that included leashed potbellies. The animals can fetch thousands of dollars each—prices that can be inflated with false descriptors, such as “teacup” and “micro.”

Pigs move through the grounds at Oinkin’ Oasis.

Eric W. Pohl

“I try to remind people that it is very uncommon for a healthy pig to weigh less than 80 pounds as an adult,” wrote Dr. Evelyn MacKay, a veterinary resident at Texas A&M University, in an email. “Although we have all seen pictures of cute, tiny pigs on the internet, the average pet pig is usually over 100 pounds.”

Over many generations, dogs have been bred to take on a range of looks and sizes. Unscrupulous miniature pig breeders have claimed similar progress over mere decades.

“They sell this micro teacup lie,” Bolling said.

Some unscrupulous breeders are worse, said Dan Illescas, who co-founded Central Texas Pig Rescue, a member of Bluebonnet EC, in Bastrop in 2016. Some breed pigs that aren’t fully grown—to give the illusion of tiny mothers—and even advise owners to underfeed pigs to keep them small, he said. Buyers who succumb to these tactics have few options.

“If I told you to only feed it a tablespoon of food a day, and you did that and it died—it’s on you,” Illescas said. “You either feed the pig and it gets bigger than you wanted, or you don’t feed the pig and it dies.”

In Search of Solutions

It was Pearl’s cute features that got Bolling’s attention, but it was her personality that forged a strong bond between them.

“When people reach out, I tell them my greatest need is always belly rubbers,” Bolling said. “These animals are super social, and physical contact and connection is what they crave most.”

According to findings published in the International Journal of Comparative Psychology, pigs live in complex social communities. They are adept at solving mazes and other tests, have excellent long-term memories, feel a range of emotions and respond to one another’s emotional states. Some experts claim pigs can outwit dogs, but don’t confuse their behavior.

As animals that live their life as prey, not predators, “pigs have different drives than dogs do,” Illescas said. “I have to tell people five times that pigs aren’t dogs. … I explain it: ‘I know you know that pigs aren’t dogs, but what you don’t know is that your brain is telling you to look for dog behavior.’ ”

Owners frustrated by their pigs often turn to the internet, where misinformation abounds.

“When you have this big pig, but you have this information you found on the internet that says pigs don’t get big, you get kind of confused because you’re not really sure what you’re dealing with,” Illescas said. “The truth is really mystified.”

CTPR, which houses more than 250 pigs, fights misinformation with likes, shares and adorable photos. The rescue’s Facebook and Instagram accounts count more than 35,000

followers, who are exposed to the realities of pet pigs. Still, it’s an uphill fight, Illescas said.

“The people who have the information—us, other rescues, people who have pigs and learned the hard way—we have enough to do,” he said.

Pet pig owners who do manage to find harmony at home know it’s a lifestyle. Pigs can’t be boarded like dogs, and they can live much longer. They’re sensitive to the weather because they can’t sweat and have hair, not fur. They require special attention. That’s why Bolling, who specializes in rehoming pigs, requires a rigorous process for prospective adopters.

“We have a great facility here, so if [a pig is] leaving here—and they may have been rehomed one, two, 10 times before—I need to know that it’s a permanent place where they’re going,” she said. “I try to tell people, ‘Think about the life you would have with a 3-year-old, and if you can’t accommodate that life for 20 years, then don’t take a pig.’ ”

Worth the Work

A pig can change a person. Wempe stopped eating meat when pigs came into her life. A chance sighting of Wayland, one of her rescued farm pigs, through a kitchen window struck something in her.

“I literally was standing there frying up some bacon, and I just saw him and it killed me,” she said. “We used to hunt. I got a rifle for Christmas one year. We were on a deer lease. We were those people.”

Web Extra: Mitsy Wempe rubs bellies at Oinkin’ Oasis.

Eric W. Pohl

Illescas stopped eating meat, too, and has forged a relationship with the vegan community in Austin, which helps with fundraising. CTPR spent more than $85,000 on operations in 2017, Illescas said, before its population more than doubled. CTPR, which adopts out pigs in good health, focuses on pigs in greatest need—those with health issues that may have suffered from abuse or neglect. Veterinary students at Texas A&M benefit from caring for CTPR’s pigs, which aren’t always a focus of vet curricula.

“All veterinary students receive education on swine health, diseases and management practices, though this is a smaller part of the curriculum compared to dogs, cats, horses and cows,” wrote MacKay, who helps care for CTPR pigs. “The focus has traditionally been on production-type swine medicine.”

Mini pigs are a big commitment, a message Bolling, Illescas and Wempe hope to spread among veterinarians and the public. They’re not quitting on their pigs.

“I’m a big believer in the Lord, and I felt like this was the place he was calling me to be, and it’s opened so many doors,” Bolling said.

Their stories won’t end like the rest.

Chris Burrows is a TEC senior communications specialist.