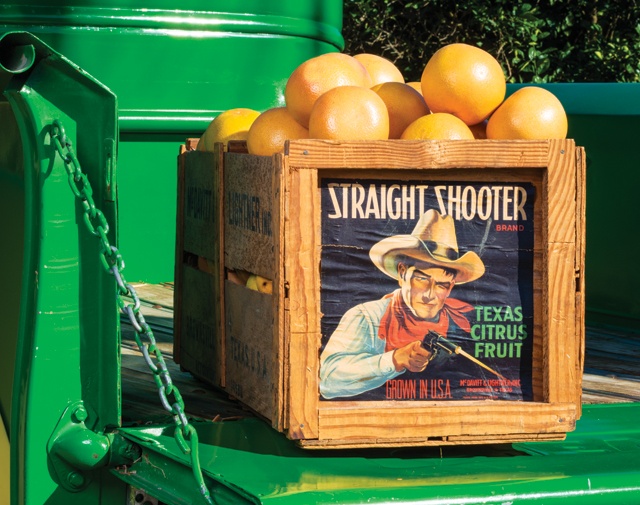

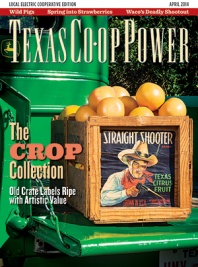

The vibrant colors and original art of the citrus crate label cradled in Dale Murden’s hands represent a cherished link to the past. “This is a cool piece of history that people have forgotten about,” says Murden, manager of Rio Farms, a private Rio Grande Valley agricultural research organization. “The colors are so brilliant it looks like it was printed today, not in 1938.”

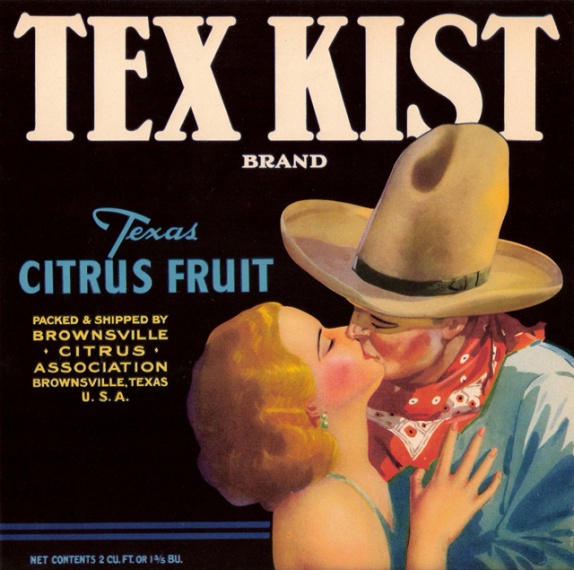

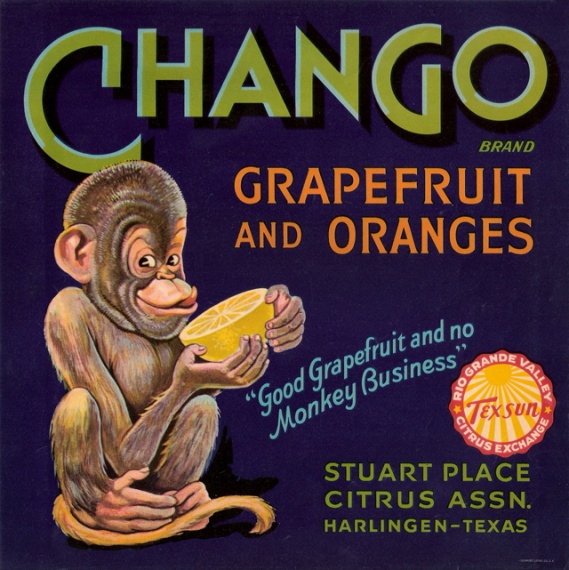

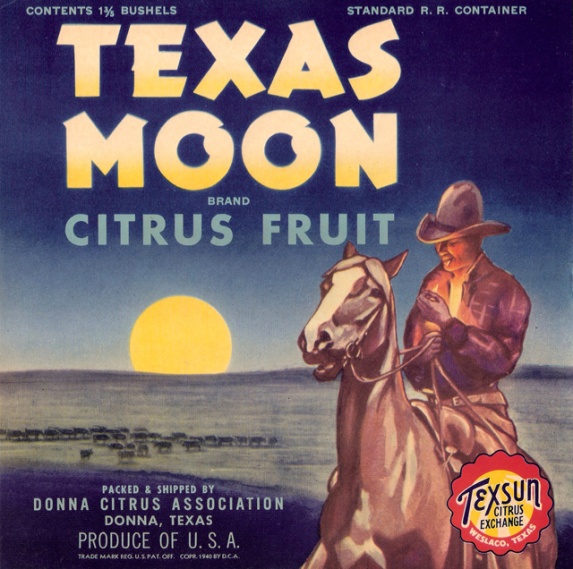

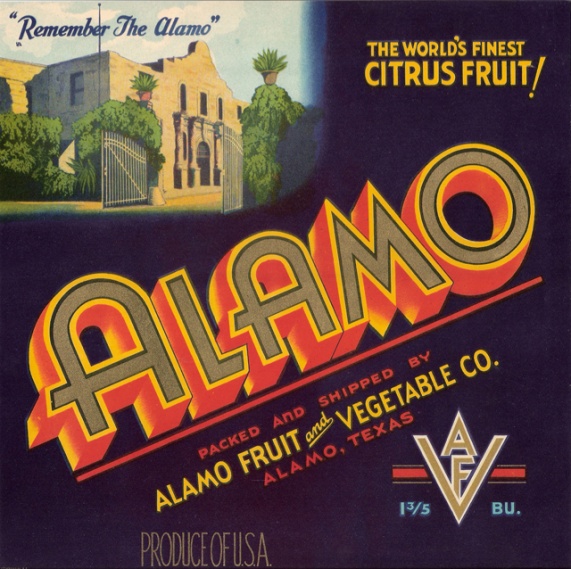

Glued onto the ends of slatted wooden crates packed with aromatic, sun-ripened citrus and shipped north, Texas fruit labels were an eye-catching marketing tool for almost 50 years. Today, the original labels rank as an American art form prized by collectors.

The glossy, square Sun Rich label from the Lindsay Gardens packing shed in Mission is one of 400 in Murden’s collection. After discovering label art and its history in the mid-1990s, he began searching the few remaining packing sheds for long-abandoned boxes of labels. “It’s a treasure hunt. For me it is all about Texas citrus, but they are getting harder and harder to find,” he says.

High on his wish list are citrus brands with a personal connection, such as Rio Farms’ elusive Rio Way and Rio Star labels. “Those would be my holy grail,” he says. “I’m always on the lookout.”

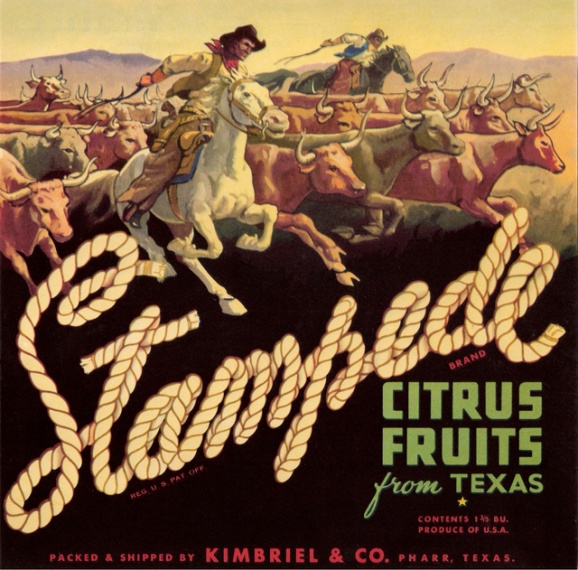

The 9-inch-square fruit crate labels, along with labels for tomatoes, yams and other produce, had their heyday from the 1910s to about 1960. The illustrations were designed to appeal to wholesaler buyers who frequented produce auctions in New York, New Jersey, Detroit and Chicago. Dazzling colors, picturesque images and stylized lettering made Rio Grande Valley packing and shipping brands easily recognizable.

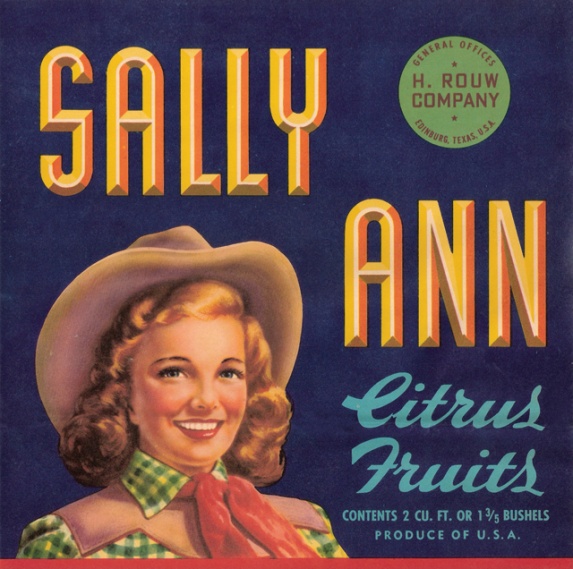

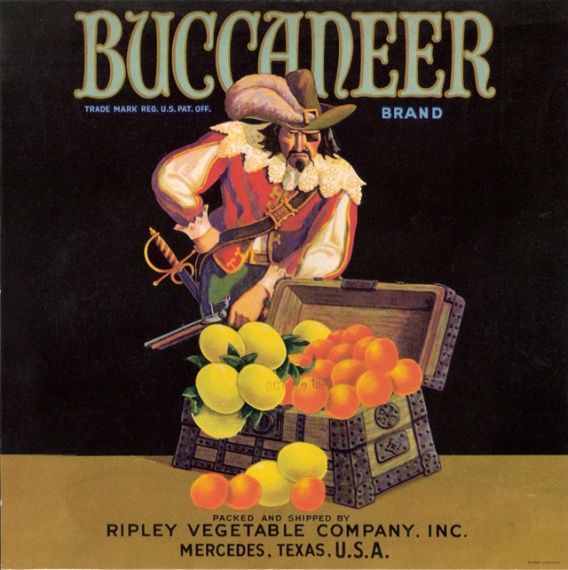

Citrus label art played up the appeal of Texas, the Rio Grande Valley and its tropical, exotic neighbor, Mexico. Bold men, cute kids, winsome women, lively animals and Mexican themes were more common images on the Valley brands than the fruit itself, an instance of selling the sizzle rather than the steak. The art frequently featured a cowboy on a bucking horse or with guns blazing or pictured on a lonesome, moonlit prairie. Some labels depicted exotic monkeys and parrots along with animals ranging from whitewing doves and deer to Assault, the 1946 Triple Crown-winning quarter horse from the King Ranch. Illustrations of men in wide sombreros, women with swirling skirts, Native Americans, old sailing ships, trains, planes and palm trees decorated labels of brands that, over time, have merged or disappeared.

In the Grove

The Rio Grande Valley once had dozens of citrus packing sheds located adjacent to rail lines. Many whistle-stop towns on the San Benito & Rio Grande Valley Railway, known as the Spider Web railroad (a precursor of farm-to-market roads), supported at least one packinghouse. Each packer used a variety of labels for its brands, with the illustrations and lettering tweaked and upgraded over the years. H. Rouw Company of Edinburg used the Rio Moon label, a Sally Ann brand that featured Norman Rockwell-style art with two children and a dog watching an orange moon rise above a citrus grove. Edinburg Citrus Association shipped under four brands: Tropic Valley, Tropic Moon, Edinburg’s Best and Mission Pride.

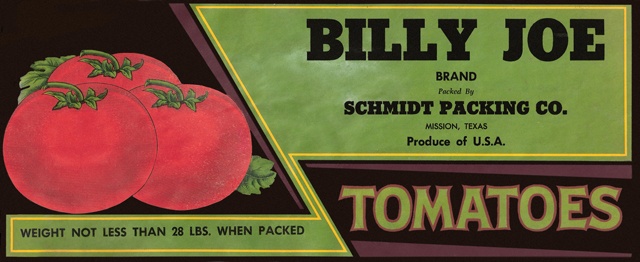

Growers and packers ordered labels displaying their children, pets, wives and houses. Family played a role in brand names, too, says Cyndie Haden, Murden’s wife. Her grandfather, who owned the Schmidt packing shed in Mission, named one label Billy Joe for his son, Haden’s dad. So Murden began hunting for a Billy Joe label, too.

The Art

Artists working for California lithographers, such as Schmidt Lithograph Company, Stecher–Traung and Louis Roesch, created almost all the fruit and vegetable labels used in Texas. The printers ran studios with as many as 100 commercial artists designing fruit and vegetable labels along with ones for soap powders, crackers and cereal boxes. Fruit label art did not rank as prestigious work and was not signed. Labels, in fact, were joint projects with illustrators, who added jazzy lettering.

By the 1930s, technical improvements in label production ushered in an era of attention-grabbing colors and more stylized, less realistic images. The four-color offset printing process created dazzling colors on cheap paper that nevertheless managed to withstand the heat and humidity of packing sheds and the cold, damp environment of refrigerated railcars.

Label artwork depicted the dancing señorita of Donnatex, the red and yellow spread-wing macaw of the Weslaco Citrus Association, the cloche-hatted beauty posed for the Stuart Place Citrus Association, the cocky rooster on the Mornin’ Judge label of the Donna Citrus Association, and the leather-helmeted pilot on the Tex-Ace label of Elsa. A few labels spotlighted Valley history: An early Monte Alto label featured the Delta Lake mansion where land developers sweet-talked visiting Midwesterners into buying Valley farms. Others like the Rio Moon label mimicked styles of famous artists.

Packing companies typically owned the rights to the label images, but the brand names rather than the art were registered. Building their brand, packinghouses used the same label design for their citrus and produce. The label art was ready-made for use in print ads and on billboards, but, truth be told, few consumers knew citrus brand names. Labels continued to be designed to catch the eye of the wholesale buyer. The sheer volume of labels shows how competitive and diverse the Valley citrus industry was.

Fruit of the Boom

By the late 1940s, with the growing popularity of the Ruby Red, the first patented grapefruit, the Rio Grande Valley was shipping 10,000 railcars filled with citrus annually. Texas supplied almost half of the grapefruit eaten in the U.S., the bounty from more than 5.5 million trees. Between 50 and 60 citrus packinghouses shipped to northern produce auctions, says Ted Brasch, whose grandfather started the Interstate brand in 1937.

Murden treasures three wooden citrus crates, dating from the 1950s, that he acquired from Mayer’s Market, a small family-owned grocery in Iowa. The crates evoked a bygone era for Sharon Mayer, who helped her parents run the store. “I have memories of opening crates like this and smelling that first whiff of citrus, then carefully setting up a display of fruit in the refrigerated cases,” she says.

Murden is not the only citrus label collector. In McAllen, Carol Pease safeguards the mother lode of Texas labels: 1,278 citrus and vegetable labels collected by her late husband, Ed. He saw the label collection as a way of preserving the history of the produce industry that he worked in for 40 years.

“Ed went through the old packing sheds searching for labels,” Pease says. “He would find labels pasted in old yearbooks of the Texas Citrus & Vegetables Growers and Shippers Association, too. The history behind them is what is fascinating.”

The abrupt switch in the late 1950s from wooden crates to cheaper, preprinted corrugated boxes left mountains of unused labels that were shoved into backrooms and attics of packing sheds. Despite the passage of time and packing shed fires, the supply of labels remains greater than the demand. While most labels today cost only a few dollars, rare citrus labels bring $225 and up.

When Carol Pease and Murden first met in November to look over Pease’s collection, they uncovered mutual friends, a shared love of label art and Murden’s holy grail, the Rio Farms labels. He also found the label produced for the packinghouse owned by his wife’s grandfather. “Did you see Cyndie’s face light up when she saw the Billy Joe label for the first time?” Murden asks, all smiles after finding the Rio Farms labels and several other gems in Pease’s collection.

Collectors such as Pease and Murden can determine a label’s age by the paper, subject, design and lettering. Western Lithograph’s labels often had a date stamp on the back. “Grown in the USA” was used from the 1920s to 1940s, while “Produce of the USA” was used from the 1930s to 1950s. Complicating label dating, Mexican fruit was packed by Valley shippers.

When Ed Pease started collecting labels, every piece was authentic. That’s no longer the case, Carol Pease warns, because people online are selling copies of labels without full disclosure.

Yet label collecting is contagious. I followed some leads, and, on the back shelf of a storeroom belonging to friends, I opened a box filled with Texas citrus shippers’ yearbooks dating from 1943 to 1983. Most of the early books had six to eight original citrus labels pasted on the pages of advertisers. Oh, my! I discovered the MarVLus label with a majestic bald eagle and the Texas Ranger label packed by McDavitt and Lightner of Brownsville. And vegetable labels, too.

Citrus crate labels chronicle the evolution and increasing sophistication of commercial design in the first half of the 20th century. The labels show history, scenic beauty and a changing society. But for Dale Murden and Carol Pease, they are pieces of Americana, beautiful in their own right.

——————–

Eileen Mattei is a Harlingen writer.