It’s another sunny December day in West Texas, and Jim Crawford crosses the fifth and final cattle guard on his two-hour drive to the McManus Ranch from his home near Ballinger. Crawford is there to shoe horses, as he has been doing on this ranch since the early 1970s. He pulls his trailer to a convenient spot near the barn.

He wears denim, lace-up boots, suspenders and his signature red-and-white polka-dot welding cap. Last he ties on the leather farrier apron he stitched himself. Crawford is wearing the same outfit I remember him always wearing when he visited as I grew up on this ranch. My dad, Beaver McManus, a member of Concho Valley Electric Cooperative, says it’s the same uniform young Crawford wore the day he met him as a junior high boy when he came out to the ranch with his great-uncle Houston Crawford.

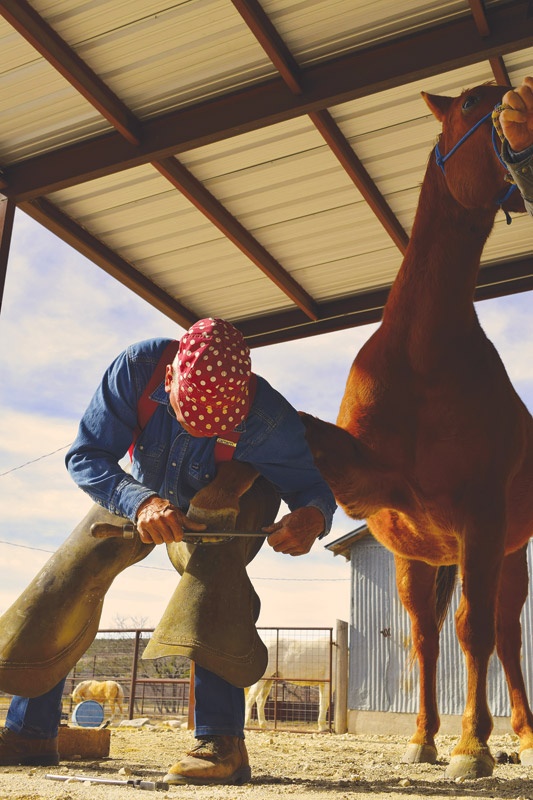

Crawford rasps one of Peanut’s hooves for a final fit at McManus Ranch in Irion County.

Kristin Tyler

When you live this far out, you look forward to visitors. The days that Crawford comes to the ranch to shoe horses are days filled with storytelling. More often than not, farriers become lifelong friends with horse owners. “I couldn’t have gotten along without him the last 30 years,” Dad says. “He’s more than someone who just came out to shoe our horses. He’s part of our extended family.”

Farrier, derived from the Latin word ferrarius, meaning blacksmith, is the professional name given to horseshoers. Many prefer to be called farriers, but others, like Crawford, prefer the simpler term “horseshoer.” No matter what they’re called, they’re necessary to the state’s equine industry.

Crawford recalls first getting the horseshoeing gig at the ranch. Houston asked him to meet at the mailbox before dawn, and the young shoer beat him there. “I think that impressed him, that he didn’t have to wait on me,” says Crawford, a member of Coleman County Electric Cooperative. Houston welcomed him to the house and made his signature extra-strong coffee. “It was boiling in the cup,” Crawford laughs. “I thought, jeez, how does his system handle that? Must be cast iron.” Nearly 50 years later, he still remembers the gray horse he shod that day.

Crawford loves his work, but he originally dreamed of becoming a calf roper.

“I had a lot of try, but I didn’t have the talent,” he jokes.

“I could win fifth if they were paying four.” The first horse Crawford shod was his own calf roping horse, Wimp, named after the horse’s grandfather, Wimpy P-1, born on the King Ranch and the first horse registered with the American Quarter Horse Association. Crawford hoped a regular horseshoeing clientele would enable him to stay at the roping gig longer.

The tools and nails he uses.

Kristin Tyler

In the spring of 1972, Crawford used his GI Bill benefits to go to horseshoeing school. An outbreak of screwworms in the summer of ’72 forced ranchers to ride their land daily to monitor their livestock. This created high demand for farriers. Crawford was getting calls to book his services before he’d completed the 10-week course. When he finished, he had a satisfying work schedule and a long list of clients. He became so busy shoeing horses he never returned to roping.

Crawford’s customers come to him through word-of-mouth recommendations. A stack of spiral notebooks tell the stories and names of most horses he’s shod through the decades.

“Showing up and having the shoe stay on made my career,” Crawford says. “When I first started, guys used their horses hard.” Originally, nearly 100% of his clients were ranchers with working horses. Now more than half are pleasure horses.

Texas ranks No. 1 in the nation for its inventory of horses, ponies, mules, burros and donkeys. Though there’s been a transition in the horse’s function from work to pleasure, horses are still big business in Texas and create a constant demand for farriers.

The tools and nails he uses.

Kristin Tyler

Why do horses need shoes? There’s an old saying, “no foot, no horse,” which speaks to the importance of a horse’s feet to its overall health. Each horse’s foot includes a mechanism that pumps blood back up to the heart, so each foot is like an auxiliary heart for the animal. A horse’s hoof is a living, growing part of that anatomy. Most components of a horse’s hoof are elastic, so they also act as shock absorbers.

When the growth of the hoof is balanced by equal wear and no disease or abnormalities are present, horseshoes are not necessary. Horseshoes are used for protection, traction and correction. Whether it is racing, ranching or rodeoing, a horse’s work is rough on its feet. That’s when shoes are necessary. Shoes also correct some problems with gait and lameness.

Horseshoeing is both art and science, and skilled farriers pride themselves on helping to keep horses sound. Farriers study the anatomy of a horse’s entire leg and are knowledgeable in the treatment of many hoof diseases, such as laminitis, navicular disease and thrush.

Crawford, who once dreamed of becoming a calf roper, found his calling in 1972.

Kristin Tyler

It’s believed that the horse was domesticated around 3000 B.C., and Egyptians and Persians are credited with creating the first horseshoes from woven reeds and grass. The horseshoe has evolved through the ages, though the steel shoe has not changed much since the mid-1800s, when Henry Burden patented a machine that could mass-produce horseshoes. Although many synthetic shoes have come on the market in recent years, the majority of farriers still put on a steel shoe that’s either hand-forged or ready-made and shaped either cold or hot and fitted to the animal.

Before a shoe is placed, the farrier will clean and trim the hoof to ensure a level and balanced foot. Even hooves that go without shoes likely need to be trimmed on a regular basis. The farrier will then customize the shoe to mimic the shape of that horse’s hoof wall. The shoe is nailed outside of the wall from the bottom, so the nails penetrate the portion of the hoof that has no feeling.

The Texas Professional Farriers Association comprises about 200 members that meet regularly for continuing education. Texas does not require farriers to have a license to practice, but the TPFA helps members achieve certification through the American Farrier’s Association. Certification exams include a written and a practical component. The TPFA also hosts clinics and competitions throughout the year.

“A shoe should be a complement to the horse, not an interruption,” says Danny Anderson, TPFA president. Anderson owns Indian Creek Forge in Whitesboro and is a member of PenTex Energy. He says the organization is growing, and there is an up-and-coming generation of farriers.

Crawford shows up for jobs with racks of horseshoes in the bed of his pickup.

Kristin Tyler

Veterans in the Industry are passing along their knowledge of the trade to new members, and they don’t all look like Crawford. Women have gotten involved.

According to the 2019 Farrier Business Practices Report produced by American Farriers Journal, 18% of farriers are women, up from 8% reported three years prior. In 2018 Cornell University admitted its first all-female class to its farrier program.

Nichole Smith co-owns SS Horseshoeing in Wichita Falls with her husband, Stephen, and is leading the way in the growing sector of female farriers. She was the first woman in the world to achieve multiple farrier certifications and has mentored other women.

“I’m really excited that so many young ladies are getting involved and doing so well,” Smith says. “Some ladies are small-statured, and they need to be prepared to use their brain to overcome some of the challenges. I’ve always been welcomed in this industry, like family, and I appreciate that.” Smith forges all the steel and aluminum shoes she sets.

Although technology like 3D printing is quickly advancing this industry, there’s no replacement for the friendly smile and personal care for horses a farrier brings.

Crawford smiles as he looks back at his career: “Having people know that I did a good job and knowing that I was appreciated—that’s the reward.”

Brenda Kissko is a native Texan and grew up on the McManus Ranch. Visit her online at brendakissko.com.