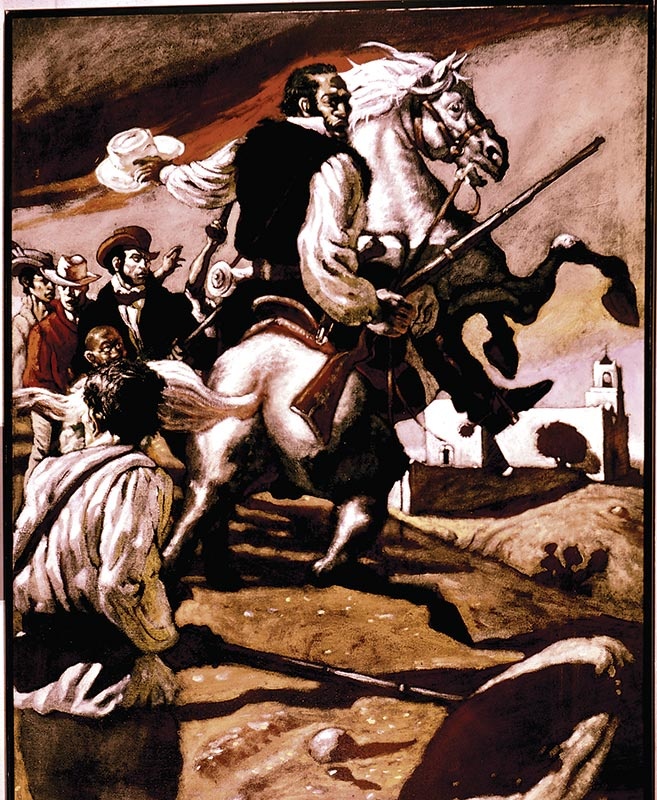

Samuel McCulloch Jr. was biracial but considered a free Black man when, as a soldier with the Texian army, he was wounded during the Battle of Goliad on October 9, 1835, and considered the first casualty of the Texas Revolution. A musket ball shattered his right shoulder, and despite his injury and service, the postwar Texas government ordered him and all other free Blacks to leave.

Then, in a series of conflicting legislative moves, things got confusing. Could he stay, or did he have to go?

McCulloch was born in 1810 in South Carolina. His father was white, and his mother was Black, but no other records of her status exist. McCulloch Sr. moved his son and three daughters, all considered free, to Texas, where they settled near the Gulf Coast in what is now Jackson County in May 1835.

The Battle of Goliad was the second skirmish of the revolution, coming one week after the brief skirmish known as the Battle of Gonzales and just four days after McCulloch joined the Texian army as a private with the 50-man Matagorda Volunteer Company. When the force attacked a Mexican army camp, McCulloch was first to enter the fort and the lone soldier wounded. The injury left his shoulder permanently disabled.

Kermit Oliver painting courtesy UTSA Special Collections | University of Texas at San Antonio

After the war McCulloch’s residence status quickly began to twist and turn. Initially, the republic’s constitution, adopted in September 1836, prohibited citizenship for “Africans and the descendants of Africans and Indians” and required all free Blacks to apply to the Congress for permanent residence.

McCulloch made the required application for himself and his sisters in 1837, recounting his military service and stating that he had been “deprived of the privileges of citizenship by reason of an unfortunate admixture of African blood.”

On June 5, 1837, the republic passed a law that permitted free Blacks to keep their residency if they had been living in Texas before the Republic’s Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836.

With his petition still pending, McCulloch saw his residency status further imperiled on February 5, 1840. That’s when an act was passed to prohibit the immigration of free Blacks and demand that all free Black residents vacate the republic within two years or be sold into slavery.

McCulloch filed a successful second petition, likely because of the Ashworth Act, passed December 12, 1840. This legislation provided that the Ashworth families, Black relatives in Jefferson County, could remain in Texas after influential whites intervened.

As a disabled veteran, McCulloch was eligible for a land grant and was awarded one league (4,428 acres) of land, two-thirds of which he chose to ranch and farm near Von Ormy.

Despite his land and his disability, McCulloch soldiered again, fighting in the battle of Plum Creek in 1840 against Comanches and serving as a spy during the Mexican invasion of San Antonio in 1842. He died in Von Ormy on November 2, 1893.

Michael Hurd is an author, historian and journalist who has written for publications such as USA Today, the Austin American-Statesman and The Houston Post. He is a noted expert on football at historically Black colleges, and as director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University, his research focuses on the 500-year history of African Americans in Texas. His most recent book is Thursday Night Lights: The Story of Black High School Football in Texas. A native Texan, he lives in The Woodlands.