The three 50-year-old Mason jars of canned green beans clinked together in a box of family mementos my husband-to-be brought with him when we got married in 1993. They were the last of several jars salvaged from his grandmother’s storm cellar near the community of Old Glory, where she had stashed them in the late 1940s.

These jars were miniature monuments to the virtue of hard work, the backbreaking processes of planting and harvesting and subsequent days of canning in a hot kitchen. It was part of farm life. But to me, a child of the city, the jars sloshing with murky liquid and stems eerily waving among the beans were scary. I wondered how fast I would die if I opened a jar and ate its contents.

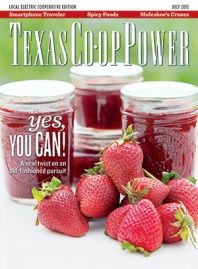

My disconnectedness from the past is typical of a post-World War II generation that looks askance at food preparation. So much easier to go out to eat. But in the past five years, that default setting has changed. “2014 was a record year in the jar sales industry,” says Steve Hungsberg, director of marketing for Jarden Home Brands. The statistic is meaningful because Jarden owns Ball, the leading manufacturer of Mason jars. The Ball brothers founded their company in 1880 and in 1884 began making home-canning jars, which could be easily sterilized and visually inspected for flaws. Mason jars have remained the most popular jars used for canning to this day.

Part of the reason for the sales explosion in Mason jars is the DIY boom, the do-it-yourself juggernaut whose culinary equivalent translates into food preservation. The phenomenon of eating healthier has tracked the same trajectory as the surge in popularity of farmers markets, where locally grown food is the main draw. “It’s all about having control over what goes into our bodies,” says Elizabeth Comiskey, who has monitored the tandem trends. She is the membership and outreach coordinator for the Farmers Market Coalition, which has staff in states all over the country, including Texas. “There is a movement toward more healthy eating; and that is not a trend, it’s a paradigm shift.”

Canning is a symbol for this quiet revolution. “We started to see the revival of canning from people interested in local food,” says Comiskey, who notes that there has been a 76 percent increase in farmers markets since 2008, with Texas showing one of the biggest increase in numbers. It’s not just among urbanites, either. Rural enthusiasts are eager to know more, too.

Amy Wagner is the county extension agent for family and consumer sciences for Randall County, in the Panhandle. Wagner started teaching canning five years ago. “Before that,” she says, “there was no audience for it.” She now turns people away from her classes, which vary from six to eight hours a day to two days. “People come here to refresh their knowledge,” she says, “or to learn what they watched their grandmothers do.”

Wagner’s counterpart at the other end of the state is Connie Sheppard in Bexar County, whose job it is to revive what she calls “heritage” skills—all those things your grandmother did to keep the family going. Sheppard works with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service’s Backyard Basics, an initiative that promotes healthy living by providing information about the benefits of homegrown and homemade foods.

“A lot of people aren’t handing down those skills any more,” says Sheppard. “So we teach classes, sponsor weekends at a ranch where we reintroduce heritage skills, and conduct expos in an eight-county region around San Antonio.”

There’s a lot to learn—or relearn. Canning can be quite complicated for an endeavor where the rules have hardly changed since 1880. Canners have two options: hot-water bath and pressure canning, which is suitable for processing low-acid or no-acid foods such as pumpkins, potatoes, meats, poultry and fish. Fruits, jams and pickles require the hot-water bath method.

Supplies for each are similar. The short version of the hours-long process: Clean the jars, line them up on the counter and get the equipment ready. Prep the ingredients, fill the jars, wipe the rims, and screw on the lids and bands. Boil. Remove and cool. When the lids make a popping sound, the seals are forming, which is the sign that the process is complete.

And for those, like me, who wonder how long the product will be safe to eat, Wagner has the answer: “You should consume what you have canned within the year.” Those 50-year-old green beans from grandmother’s cellar? “Definitely not safe,” she says.

Safety in numbers is another of Wagner’s mantras. “I like to can with a group of friends,” she says, “because it’s more fun.” But it’s also a good idea because safety is always a concern. (The pressure cooker could explode, for instance.) “There’s so much to think about,” she says, “If you forget something, someone else will remember it.”

Communication is a huge factor in the endeavor. One of Wagner’s students is Joann Terrell, a homemaker who lives in Borger. She joined the class with her teenage daughter. “I wanted to make healthier meals for my family,” she says. But the community aspect beckoned. “Nobody talks to each other any more,” she says. “When we get a group together to can, it’s better than the Internet.”

In fact, the Internet has been instrumental in bringing old-fashioned values to a different audience. Austin-based Kate Payne could be the poster child for the new generation of food preservationists. Her wildly popular blog, “The Hip Girl’s Guide to Homemaking,” has revved up the 1,200 subscribers to her blog, the 4,000 recipients of her weekly email updates and the 25,000 other viewers who click in every month. Payne spreads the word about pickling, fermenting, making jams and jellies, and pressure canning (back by popular demand) in her classes—two a month in Austin (“Except last month I taught five,” she says). She’s also on the road with a daunting travel schedule that includes upcoming trips to Marfa; Nashville, Tennessee; and Saratoga Springs, New York.

Payne developed a following after she wrote her first book, “The Hip Girl’s Guide to Homemaking” (Harper Design, 2011). That was followed by “The Hip Girl’s Guide to the Kitchen” (Harper Design, 2014). Payne expected her fan base for both books to be 20- or 30-something women, but that didn’t turn out to be the case. “It’s really 20- to 60-somethings, and that includes men,” she says. She attributes the surge in interest to several factors, but one in particular. “Canning is a way for people to get together,” she says, “to share time and food.” It’s also a bonus that some of the do-or-die rules of canning have been relaxed.

Changes in the canning process are rare, but when they do happen, people take notice. A recent announcement from Jarden that it is no longer necessary to sterilize lids caused a stir in the canning blogosphere. You also are no longer required to seal your jams and jellies with paraffin wax seals—a messy process that didn’t always work, anyway.

Payne notes that new equipment, such as small-batch canning baskets, is now available that enables the cook to make more manageable serving sizes. But the real revelation was that it was possible to make smaller batches—that what you canned wasn’t dependent on preserving the fruits of a big harvest as in bygone days. Had Payne known that when she plunged into her first canning adventure six years ago, she would have been spared the enormous yield she achieved from the 14-pound box of peaches.

Perhaps most important, though, is that canning is less laborious now. Sheppard still remembers some of the preliminaries to a weekend of canning, like picking blackberries along the side of the road when she was a young girl. “That was not fun,” she says. Now you can go to the farmers market and come home with your bounty.

“It’s also become more user-friendly,” notes Sheppard. Canning was never a means to instant gratification, but time-saving options are available. For example, the website mrswages.com now offers two ready-to-use mixes—salsa and jalapeño pickle relish. “You only have to stir and you’re done.” Sheppard says. “And you can still say you made it.”

Canning is not necessarily an all-day project. Payne cans 2 to 4 pounds of fruit or vegetables in a couple of hours or so. That represents a manageable commitment for a clunky process that’s survived against plenty of cultural odds. “Canning is here to stay,” predicts Sheppard, citing practical reasons such as health.

But canning is also about something else, such as how you spend your time, who you spend it with, and what’s important to you. Maybe that’s the real reason it’s booming now. As Hip Girl Kate Payne says, “I can’t imagine my life without it.”

——————————-

Read more of author Helen Thompson’s work at seeninhouse.com.