The tree that nearly everybody calls cedar is really Ashe juniper, except when it’s another kind of juniper or cedar. Nearly everybody knows this, but the tree is still—and will most likely always be—referred to as cedar, as will be the case here. In the Lone Star State, the cedar is native to the Hill Country and Central Texas, but it hasn’t always been as native as it is now. That is to say there is a lot more of it than there used to be, and sufferers of cedar fever will say there’s way too much of it. Landowners and scientists blame it for crowding out native hardwood species and lowering water tables. When it comes to cedar, familiarity has bred contempt.

At a time when most people living in Texas made their living from the land in one form or another, the cedar brakes were always there to be exploited. One of the earliest uses of cedar was the burning of it to make charcoal, which heated stoves and flatirons of the day. A hotbed of this kind of activity was along the banks of the Guadalupe River from about New Braunfels to Sisterdale, an area that came to be known as Charcoal City. German settlers first discovered the market for charcoal and took to burning it between planting and harvest. By the 1880s, charcoal burners from Georgia, Indiana, New York, Tennessee, and even Ireland and England had made their way into the Guadalupe River Valley and were turning cedar into cash.

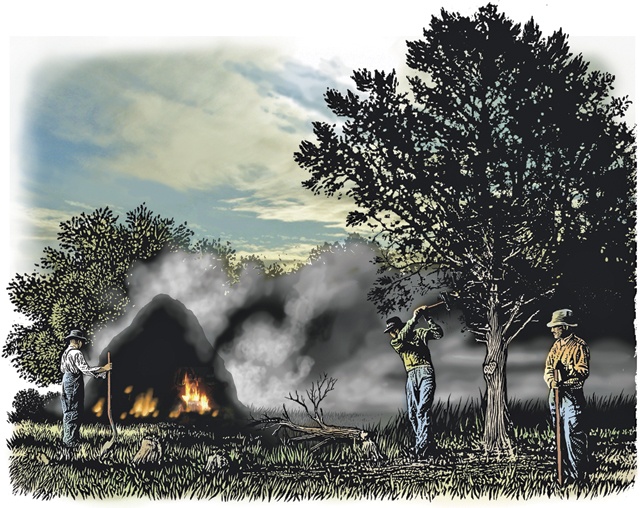

The cedars were cut while they were still green to ensure a slow burn and then chopped into poles and the bark peeled away. Two or three cords of wood were arranged in a pyramid in a kiln or pit, then covered with dirt. A hole was left in the top of the stack, tepee style, so smoke could escape. A hole at the bottom was closed after the fire was lit. After that, the charcoal burner had to “hurry up and wait” for the fire to do its work, which usually took a few days. The Guadalupe Valley became sort of the Smoky Mountains of Texas as a haze of smoke, redolent of cedar, hung over the valley for much of the year.

The whole process could go up in smoke if air got into the kiln and flames broke out. Flare-ups had to be extinguished quickly with dirt or water, or else the cedar would burn into ash rather than smolder into charcoal. When the cedar was charred to perfection, the fire was put out and the charcoal raked into sacks, put on wagons and hauled into town.

The best markets for Hill Country charcoal were San Antonio and Austin, so most of the burners loaded their wagons with charcoal and hauled them to those towns. Author J. Frank Dobie recalled hearing the burners call out, “Char-r-coal” as they drove their wagons through Austin in 1914. A wagonload could bring from $8 to $24, depending on supply and how many burners might be cut off from the market by high waters at a time when there weren’t a lot of bridges and Hill Country rivers ran undammed and untamed. Still, charcoal was money in the pocket any time of the year and could be counted on when corn and cotton failed.

Opportunities for the charcoal burner diminished quickly after World War I. Railroads and Model T trucks made it easy to haul cedar posts to market without going to all the trouble of turning them into charcoal first. Use of charcoal-heated flatirons had decreased, too, and the development of barbed-wire fences created a great demand for cedar posts.

Many of the descendants of those early charcoal burners changed with the times and became what were called, sometimes derisively, cedar choppers, who made many of the cedar fence posts you see in the Hill Country today. There was plenty of cedar for the choppers to chop.

Overgrazing played into the cedar’s hand, as did the practice of burning the prairies and clearing of cedar to allow shorter and more nourishing grasses to grow in their place. As the number of trees declined, excess runoff made the soils too shallow to support very much grass, which cleared the way for cedar and brush to take over the landscape. The cedar was back to stay.

Like their charcoal-burning ancestors, cedar choppers were noted for their independence and a lifestyle unencumbered by a lot of modern complications. Also like their ancestors, they have all but disappeared from the scene. The cedar, though, is still very much with us.

——————–

Clay Coppedge is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power and is the author of Hill Country Chronicles, available from History Press.