There’s a 15-foot-tall, 100-year-old mystery on the campus of the University of North Texas in Denton. In a tree-shaded area near the general academic building, a regal bronze sculpture of artist Diego Velázquez on horseback overlooks students and staff as they go about their days.

New Yorker Constance Whitney Warren sculpted Velázquez, a 17th-century painter, when she was living in Paris after World War I. The family of billionaire Harlan Crow donated the piece to UNT in 1994. Nobody seems to know why.

“I do not have the answers,” says Holly Hutzell, art registrar for the university. “We do not have a record as to why the donor gifted it to UNT. Nor do we know why the artist depicted the Spanish master on horseback.”

But 200 miles north and south of Denton, up and down Interstate 35, iconic Western statues by Warren on the grounds of the capitols of Texas and Oklahoma need no explaining. Both bronzes depict life-size wooly-chapped cowboys astride broncos rearing back over cactuses. Along the path of the former Chisholm Trail, these century-old works could not be more at home. Right?

It was 100 years ago—January 19, 1925—that The Austin Statesman reported several thousand Austinites, visitors and lawmakers gathered at the Capitol and watched as two men dressed in cowboy garb pulled a white sheet from the newly christened Texas Cowboy Monument—a “tribute to the rough and romantic riders of the range,” reads a weather-worn plaque at its base.

It was the day before Texas’ first female governor, Miriam A. “Ma” Ferguson, was sworn into office, and crowds were swarming in anticipation.

“There is not another place where the statue of a cowboy can with such fitness and such propriety be placed,” said a representative of the sculptor’s family, Charles Cason, at the unveiling. “Texas was the cowboy’s home, and the very name ‘cowboy’ brings to every American’s mind the name of Texas with all her glorious traditions and romance of the endless ranges.”

Warren was born in 1888 to an affluent New York family, and despite a weekslong honeymoon through the American West after her marriage to a French count, in 1912, there’s no evidence that she ever set foot in Texas.

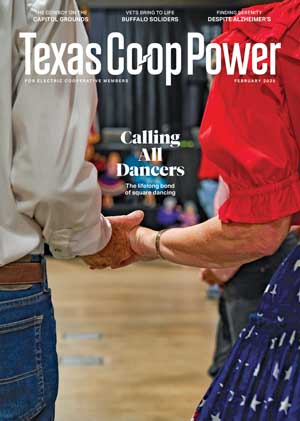

The Texas Cowboy Monument on the grounds of the Capitol.

Caytlyn Calhoun

Constance Whitney Warren’s Cowboy No. 2 was sculpted in Paris in 1921. The State Preservation Board cleans the bronze work each fall.

Caytlyn Calhoun

“At an early age, she gained a fascination for the West from stories told by her father of his experiences as a mining engineer on the frontier,” writes An Encyclopedia of Women Artists of the American West. Warren moved to France after the honeymoon, and when World War I broke out, she chauffeured English officers.

After the war, she poured herself into sculpture, executing some 100 pieces—mostly horses—between 1920 and 1930.

“A sharp observer of anatomy and a vigorous modeler, she was at her best with figures in violent action,” Stuart Preston of The New York Times wrote in 1953.

Among those works was Warren’s Cowboy No. 2, sculpted in 1921. It was exhibited at the 1923 Paris Salon, a premier annual art exhibition, and missed a bronze medal by two votes, instead claiming an honorable mention.

“This was prestigious recognition for an American woman artist,” wrote the late Scott Sullivan. “The Cowboy was praised in the French press and highly popular in Paris. Cason told Gov. [Pat] Neff that the artist wished to donate the bronze to a western state. The governor agreed to accept it on behalf of Texas.”

No one has done more to unravel the mystery of Warren than Sullivan, former professor of art history at UNT and later dean of Texas Christian University’s College of Fine Arts.

Cowboy No. 2 was shipped to New York from Paris several months before the dedication in Austin.

It wasn’t long before Oklahoma decided it needed a Warren bronco. Its Tribute to Range Riders, installed in 1928, was that capitol’s first art piece.

The dedication of Constance Whitney Warren’s bronze statue January 19, 1925.

Courtesy Cattle Raisers Museum

Warren and the count divorced in 1922, she returned to the U.S. a few years later and in 1930, she committed herself to Craig House, a discreet asylum in upstate New York. Almost nothing is known of Warren’s later years. She died in 1948.

After UNT received the Velázquez piece in the 1990s, Sullivan went to work solving its mysteries.

He made contact with some members of Warren’s family in Massachusetts, and during the course of his research that formed the basis of a 3,000-word article published by the Gilcrease Journal in 2015, he discovered that a sculpture of Velázquez by French artist Emmanuel Frémiet was installed at the Louvre from 1893 to 1933, likely inspiring Warren’s Velázquez in Denton.

Sullivan’s research brought much-deserved detail to Warren’s life. She was among few female sculptors of the early 20th century with the skills, means or ambition to produce art that typified the American frontier. She was a pioneer accepted by pioneers of another sort.

“Warren deserves greater recognition for her work,” Sullivan wrote, “and for her willingness to follow her imagination into a male-oriented and male-dominated arena largely unexplored at the time by female artists.”