Elmer Kleb didn’t like school.

The truth is he didn’t like people much, either. What he did like were birds, trees and solitude. His preferred companion was a black buzzard with a broken wing that lived with him in his run-down house on 133 acres. The buzzard apparently didn’t mind that the century-old dwelling had no electricity or running water.

“When I first visited the property, I was immediately enchanted with both the site and the hermit who owned it, Elmer Kleb,” says Andrew Sansom, then executive director of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, who visited the home for the first time in the late 1980s.

Despite his eccentric and reclusive lifestyle, Kleb left something priceless for the people of Texas. “I learned that Mr. Kleb had inherited the land when it was a cultivated field,” Sansom says, “and he spent his life finding native trees and other vegetation and replanting them on his land so that when I got there, it was a lovely mature woodland.”

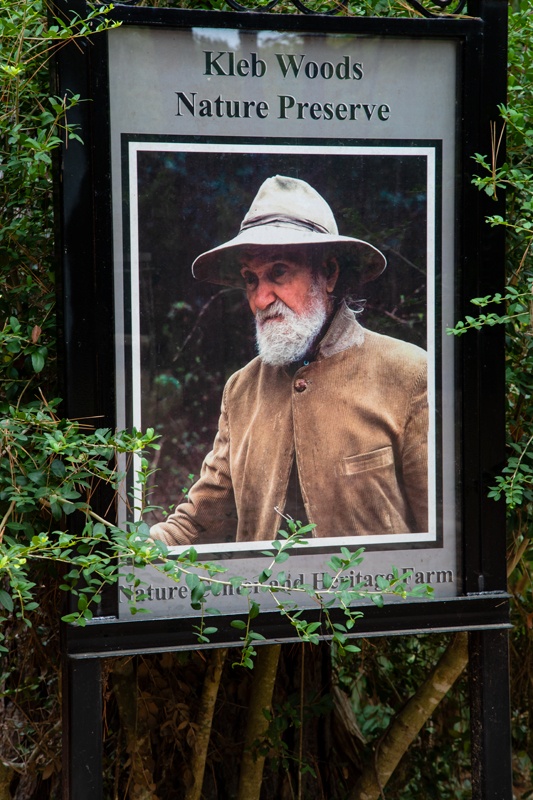

A sign shows Elmer Kleb, former owner of the property that became the nature preserve.

Larry Ditto

Today, Kleb Woods Nature Preserve, 8 miles west of Tomball and 40 miles northwest of Houston, offers a rare commodity: silence. Silence, lightly seasoned with birdsong. The preserve attracts bird-watchers, hikers and nature enthusiasts from around the world. The story of why this secluded hideaway exists at all is as eccentric as its former owner.

Kleb’s great-grandfather, Conrad Kleb, emigrated to northwest Harris County from Germany in 1846. He purchased 107 acres and established a family farm. Andreas, one of Conrad’s 14 children, bought a separate farm in 1871 for about $250 near Muschke Road, close to the German immigrant community of Rose Hill. Edward, Andreas’ son, and wife Minnie inherited the farm from Andreas in 1903, grew vegetables and cotton, raised cattle and sheep, and built a simple wood-frame house on the property. They had two children, Elmer and Myrtle.

Elmer, born in 1907, and Myrtle, in 1913, attended Rose Hill School, but Elmer didn’t get along with other boys and became the target of bullies who taunted him with the name “Lumpy.” He quit school sometime between the fourth and seventh grades (family stories are not precise) to help his parents on the farm. He rarely left the property thereafter.

“Elmer had a condition that was eventually recognized as a form of autism,” says Fred Collins, director of the Kleb Woods Nature Preserve. Collins has invested years researching the Kleb family and restoring the site’s dilapidated buildings. “When asked to do something,” Collins says, “Elmer would insist on an explanation of why the job had to be done. Without that explanation, he wouldn’t tackle the task.”

Pond at Kleb Woods Nature Preserve.

Larry Ditto

Kleb inherited the farm after his parents and sister died. With no one left to explain what jobs needed to be done, he stopped maintaining the property. Grapevines and trees, most of them planted by Kleb and his father, grew uncontrolled.

“Elmer no longer maintained the fences,” Collins says, “and allowed his livestock to wander freely, getting into neighbors’ crops and gardens. Eventually the county sheriff rounded them up and sold them.”

A small man with tangled gray hair and a long beard, Kleb was considered “peculiar” by neighbors, as his mother had been. His sister, Myrtle, endured periodic bouts with mental illness and died in her early 20s.

Kleb never married and had no children. With no source of income, he had to rely on relatives and friends for food and money, occasionally making forays into his neighbors’ gardens uninvited. Collins explains that although Kleb did drive as late as the 1970s, in later years, he walked wherever he went. When yaupon and pine trees grew up around the windmill and prevented the blades from turning and pumping water, even the single cold-water faucet stopped working.

As Kleb withdrew from the surrounding community, North Houston’s suburban population exploded. Property values and taxes soared. Kleb didn’t understand why he needed to pay taxes, so he didn’t.

A barn and flower garden on Kleb’s former farm.

Larry Ditto

When tax collectors came to the property, Kleb vanished into the thick woods until they left. Even though he didn’t open the tax statements—after his death, a collection of unopened tax bills was found in a trunk—Kleb knew something had to be done. In 1986, he wrote a letter to the Houston chapter of the Audubon Society asking for help. Members of the Audubon Society tried to raise the money to pay the tax lien that, in 1988, was $170,000—but the effort failed.

His property was worth an estimated $750,000, yet Kleb was penniless. Over the years, relatives tried to persuade him to sell a small part of his acreage to save the rest. He refused. After the Audubon Society failed to raise the funds to pay the past-due taxes, a county judge declared Kleb incompetent and ordered the property to be sold.

Steve Radack, a Harris County commissioner, intervened to prevent the immediate sale. That’s when Terry O’Rourke, Harris County assistant district attorney, contacted Sansom at TPWD.

“We managed to arrange a grant to Harris County, which paid the taxes, provided Mr. Kleb with the means to live out the rest of his life out of poverty and establish a wonderful park in his name,” says Sansom, now the executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University.

The grant from TPWD amounted to $737,500. With that money, Harris County purchased the land in 1991, paid off the tax bill and set up a trust to take care of Kleb. As Sansom notes, Harris County commissioners allowed Kleb to remain in the house for the rest of his life. Although plans to transform the Kleb woods into a nature preserve got underway during his later years, the acreage surrounding the house remained untouched until Kleb’s death in 1999 at the age of 91.

Bluejays

Larry Ditto

“Texas Parks and Wildlife contacted me at the beginning of this saga and asked me if I could try to meet with Elmer,” says Ted Eubanks, then president of the Houston chapter of the National Audubon Society. “I went out to the property and found him, and within a short time struck an unlikely friendship with him. He would call me at home—he would walk to the nearby store to use their phone—and talk endlessly about wanting to save his property as a preserve.”

Kleb left an indelible mark on Sansom, too. “For many years, I kept a photograph of the old gentleman on my wall in the executive office at Parks and Wildlife to remind me of his life’s work and the privilege of having known him and playing a small role in helping him accomplish his dream,” Sansom says.

Kleb Woods Nature Preserve, located in northwest Harris County on FM 2920, is open from 7 a.m. until dusk. Visitors may wander among the restored historic farm buildings or take shady trails that lead through towering pine and oak forests and scattered wetlands. A new nature center houses an auditorium and classroom, which attracts groups interested in birding and local history.

“Kleb Woods offers a unique sanctuary in the midst of an urban landscape,” says park visitor Cynthia Beeman. “Walking the trails, enveloped by the trees, birds and verdant heart of the woods, one can certainly understand Elmer Kleb’s tenacious hold on the land and can almost feel his presence. It is easy to picture him sitting on the porch of his home, completely at peace with his surroundings.”

Today, Kleb Woods opens a window into the environmental and cultural history of Harris County. The preserve exists because of an unlikely alliance of environmentalists, government officials and lawyers who helped a reclusive man save his beloved wilderness from becoming another subdivided housing development.

Martha Deeringer, a member of Heart of Texas EC, lives near McGregor.