Randy Deming often walks his 10 acres of rural land in Callahan County, near Abilene, always on the lookout for a flower, insect or bird he hasn’t spotted before.

Using an app called iNaturalist, he documents the native grasses, yuccas, Ashe junipers, live oaks and other plants that grow there. Thanks to the app, Deming learned in 2021 that one of his flowering species could be one of only a few remaining populations in Texas.

“I took pictures of a pretty flower and forgot about it,” recalls Deming, a member of the Texas Master Naturalist Program and Taylor Electric Cooperative. “A few months later, I was skeptical when someone contacted me through iNaturalist and asked to see my large-flower beardtongues.

“When they told me how rare they are, I was excited,” Deming says. “I could have mowed them down! Now I’m watching over them.”

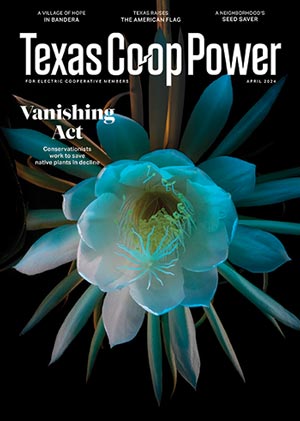

Texas Poppy-Mallow

Anna Strong | TPWD

In the future, large-flower beardtongues—a tall, erect perennial with tubular purple blooms—could be legally protected if researchers collect enough ecological data to substantiate the designation. In the meantime, 437 other Texas plants have already been designated by the state as “species of greatest conservation need,” meaning they’re in decline and need attention. Some of those species require even more urgent measures. These are further labeled as threatened or endangered.

The two legal terms stem from the Endangered Species Act, a federal law enacted in 1973 to protect and help recover the nation’s imperiled plant and animal species and their habitats. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service oversees the federal list and partners with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, which manages the Texas list. A species can be federally and state protected, such as shrubby Texas snowbells in the Hill Country, or just one or the other.

However, the process for federally listing a species can stretch out for years. Consider the bracted twistflower, a tall annual with lavender flowers that has been increasingly lost to urban sprawl and hungry herbivores. Found only within the Edwards Plateau, the wildflower has been marked as imperiled since 1975 and was petitioned for federal listing in 2014. In May 2023—nine years later—the USFWS finally listed the bracted twistflower as threatened. In Coryell County, the imperiled Texabama croton faces similar challenges.

Plants of all kinds in Texas face many pressures. Every year, development scrapes away one natural area after another. Invasive plants, agriculture, poaching, mining, weather, loss of pollinators, and land and water management also negatively impact the state’s flora.

But does it really matter if a few of Texas’ estimated 5,000-plus native plant species go away? The answer is yes.

“We have biodiversity for a reason,” says Anna Strong, a rare species botanist with TPWD. “Each organism interacts with others in specific ways. Regardless of whether it’s rare or common, if we take out one organism, we don’t know the implications amongst all the organisms. If we take out one flower, we may take a food source away from a specific insect that relies on that species.”

At the San Antonio Botanical Garden, botanist Michael Eason works to conserve and propagate rare Texas plants. “We have more than 90 species in our collections,” Eason says. “Some are displayed in our gardens, which helps to educate the public. Others are seed collections, which haven’t been propagated yet.”

One of those species, prostrate milkweed, a low-growing perennial, is endemic only to Starr and Zapata counties and northeastern Mexico. Since at least 1980, invasive buffelgrass, road construction and development have drastically reduced its numbers. After several petitions to the USFWS, prostrate milkweed—an important monarch butterfly host plant—was federally listed as endangered in March 2023. The agency also designated 661 acres as critical habitat needed by the species to survive.

Turner’s Cliff Thistle

Michael Eason | San Antonio Botanical Garden

Texas Snowbell

Chase Fountain | TPWD

For his part, Eason spent five years tracking down the scarce milkweeds and collecting seeds, then having a milkweed specialist grow the plants to maturity. “We ended up with 150 plants,” he says. “We passed some to other botanical gardens. We’ll install some in our rare plant gardens. The remainder will be kept for perhaps reintroductions in South Texas and donations to other institutions with the Center for Plant Conservation.”

Headquartered in Escondido, California, the CPC is a nationwide network of organizations working together to save imperiled native plants. The San Antonio Botanical Garden partners with the CPC, as do the Botanical Research Institute of Texas at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, Mercer Botanic Gardens in Humble and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin.

As part of its conservation efforts, the wildflower center stores seeds of 575 Texas plant species for research and sharing with botanical gardens and conservation organizations. The seed bank, housed mostly in freezers, also serves as an insurance policy against the loss of imperiled species.

“We visit wild populations that we have permission to access, either on public land or through contacting landowners,” explains Jonathan Flickinger, conservation collections manager at the wildflower center. “We harvest seeds from plants, but we don’t take too many because our priority is to conserve the plants in their natural habitat.”

In some cases, researchers may rescue plants by digging them up. That happened with the Texas poppy-mallow, listed as federally endangered in 1981. The tall perennial with reddish purple flowers grows in deep sandy soils along the Colorado River in four counties.

In 2010, some conservation-minded landowners asked that a population of poppy-mallows be removed from a future construction site on their property. That summer, wildflower center staff and other colleagues extracted 54 plants and fostered them in pots for three years.

“We harvested more than 3,000 seeds from them for our seed bank,” Flickinger says. “Then we identified another site where they were reintroduced.”

Bracted Twistflower

Michael Eason | San Antonio Botanical Garden

Prostrate Milkweed

Michael Eason | San Antonio Botanical Garden

Landowners play a huge role in plant conservation, namely because about 95% of Texas’ land is privately owned. When threatened or endangered plants grow on private land, landowners are not legally required to manage them under the Endangered Species Act (the law differs for listed birds and animals).

Botanists and other officials must always ask permission before accessing private land. Typically, they want to survey plant species, perhaps harvest a small amount of seeds and collect plant material for herbarium vouchers.

The Fish and Wildlife Service offers a program that provides property owners with free technical and financial assistance for improving wildlife habitat on their land. “We’re always looking for opportunities to work with landowners,” says Chris Best, USFWS botanist. “Most of the ones I’ve met want to protect their land’s natural resources.”

That aptly describes attorney Liz Rogers, a Medina Electric Cooperative member. For more than two decades, she’s welcomed researchers onto her family’s 8,000-acre cattle ranch in southeastern Brewster County, along the Mexico border. “They always show me cool things, which has made me appreciate our ranch even more,” she says.

Eason has been among many plant conservationists who have botanized the ranch’s Trans-Pecos deserts, canyons and mountainsides. “Liz has an assortment of rare plants found along cliff faces and other protected areas,” he says. “We’ve collected plants such as Turner’s cliff thistle, rockdaisy and Barton’s dalea. She also has a small population of night-blooming cereus.”

Whether rare or not, showy or inconspicuous, every native plant matters. “We shouldn’t focus conservation merely on species that have declined so far that they’re teetering on the brink of extinction,” Best says. “We should be working to keep common plants common.”