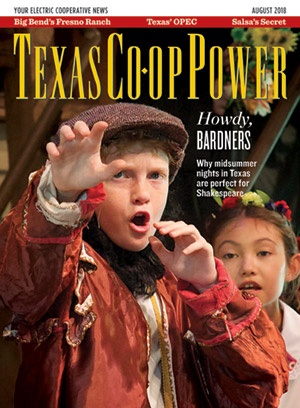

If we could, like Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “put a girdle round about the earth / In forty minutes,” and zip around the Lone Star State over summer and fall evenings, O, the Shakespeare we would hear and see!

A dozen festivals, all alike in dignity,

In fair Texas, where we lay our scene,

From famous texts, break to new creativity…

We begin in the West Texas city of Odessa. As the heat waves rise, is that a shimmering vision of Shakespeare’s Globe we see, sitting in the land of oil fields and Friday night lights? It is! The Globe of the Great Southwest, which, thanks to the vision and persistence of a brilliant high school teacher, appeared in the Llano Estacado a full 30 years before London put up its rebuilt Globe. Today, Odessa’s Globe Theatre hosts performances by the Odessa Shakespeare Festival.

Next, we fly west to El Paso and spy a group of local actors performing outdoors at Chamizal National Memorial, within shouting distance of the Rio Grande. As the players strut and fret their hour upon the stage with a touch of twang in their iambic pentameter, we soar from thence over parks filled with families sitting on picnic blankets and watching Shakespeare festivals in Dallas, Houston and Austin.

We hear comic prose, stirring verse and laughter along the Riverwalk in San Antonio, along the Concho in San Angelo and under a canopy of stars in the Hill Country nook of Wimberley, as well as on college campuses in Fort Worth and Kilgore. Last, above the gently rolling countryside of Winedale, we spy an old open-sided hay barn in the twilight, orange light spilling from inside, and we hear a voice cry out, in a timeless moment after the onstage murder of Julius Caesar:

How many ages hence

Shall this our lofty scene be acted over

In states unborn and accents yet unknown!

When it comes to the immortal Sweet Swan of Avon, all the state’s a stage. This is remarkable when you consider that Shakespeare was born almost four decades after Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, shipwrecked near Galveston in 1528 like a character out of The Tempest, became the first European to travel into the interior of Texas and wander amid its indigenous people. How did this Londoner from the time of Queen Elizabeth become our favorite playwright for a Texas midsummer night?

Shakespeare likely arrived in Texas first in an adventurer’s saddlebag or a settler’s trunk. As improbable as it might seem today, Shakespeare was a favorite of all social classes as America entered the 19th century, according to eminent Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro.

“There is hardly a pioneer’s hut which does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare,” wrote French diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville after his travels through the United States in 1831. Children learned Shakespeare’s verse from the ubiquitous McGuffey Readers, which began publication in 1836. Shakespeare’s plays—primarily the tragedies—were constantly in demand at theaters and opera houses and held their own against melodramas and farces. In October 1835, when James Butler Bonham organized a rally in Alabama to support Texas independence, he held it at the Shakespeare Theater in Mobile, a bustling town that held its first Shakespearean performance more than a decade earlier. Even Sam Houston knew his Shakespeare and quoted him often.

“Scholars and historians have now learned that language and dialect was very different during Shakespeare’s time than we thought,” says Bridget Farias Gates, artistic director of the EmilyAnn Theatre & Gardens in Wimberley. “Many consider it to be closer to the Texas dialect than to British. So, in a romantic way, this means Texans deliver Shakespeare more closely to original practice than most would think.

“I also like to think that the wide expanse of Texan land and the more laid-back nature of the Texan way of living is a closer representation to Shakespeare’s country folk characters,” she says.

The first notable professional performance of a Shakespeare play in Texas was held February 12, 1839, in Houston, when one Mr. Lewellen, who had scored a big hit in St. Louis with an equestrian melodrama co-starring his horse, Mazeppa, assayed the title role in Othello.

Competing theaters were built in Houston before the city’s first church; established actors arrived by boat from New Orleans. Theaters attracted a rough-and-tumble crowd looking for diversion—and not necessarily accustomed to the niceties of high culture. Touring actor Joseph Jefferson recalled in his autobiography that during one mid-1840s portrayal of Richard III by an aging local trouper named “Pudding” Stanley in Houston, a patron interrupted Richard’s wooing of Lady Anne to warn Anne that Richard already had two Mexican wives in San Antonio. “Nothing daunted at this public accusation of polygamy,” Jefferson recalled decades later, “ ‘Pud’ pressed his suit with ardor.”

In Texas’ early days, even soldiers performed Shakespeare, partly to stave off boredom. In the winter of 1846, shortly after Texas had joined the union, 4,000 troops of the United States Army under the command of Gen. Zachary Taylor were stationed near the village of Corpus Christi in preparation for the conflict that would later become known as the Mexican-American War.

While waiting for orders, the soldiers assembled at the Union Theater, large enough to hold 800, and began rehearsals for Othello. Out of necessity, as in Shakespeare’s London, men often played the female roles. James Longstreet, later a leading general in the Confederate Army, was up for the part of Desdemona, young wife of the noble Moor, but was deemed too tall. Longstreet’s good friend, young Ulysses S. Grant, nicknamed “Little Beauty” for his feminine good looks, took over the role, but eventually a professional actress was hired and brought in because the soldier playing Othello, as Longstreet later recalled, just could not work up the “proper sentiment” while gazing upon Grant.

After the Civil War, as Texas’ cities and towns began to develop civic traditions, the next wave of interest in Shakespeare came not from touring actors but from local citizens, especially women, with a focus on the communal enlightenment of group reading and discussion rather than performance. During the first half of the 20th century, there were at least 27 Shakespeare clubs meeting in the state, from Abilene and Calvert to Waxahachie and North Zulch; many continue proudly to this day. That same democratic impulse led to the spread of community theaters in the early 20th century as the touring system of the barnstorming-actor days faded. In the 1970s, the ripple effect from Joseph Papp’s Free Shakespeare in the Park in New York City led to a wave of park-based festivals around the state.

“Shakespeare would have loved Texas, both for its own energy and spirit and as a setting,” says Jon Mark Hogg, president of the board of directors of Be Theatre and producer for Shakespeare on the Concho. “So many of his works are set in historic or mythical places. The history, myths and wild spirit of Texas, both past and present, would have been fertile ground for the Bard.”

On the educational front, Texas scored a coup in 1946 when legendary British director B. Iden Payne, who previously had led the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Shakespeare’s hometown, Stratford-upon-Avon, came to the University of Texas as a guest professor in one of the nation’s first collegiate drama departments.

One of the country’s more unique venues for Shakespeare, the Winedale Theatre Barn, came about through a Texas miracle. In the fall of 1970, James B. Ayres, then an associate professor of Shakespeare at the University of Texas, happened to visit the Winedale Historical Center near Round Top and meet the legendary Miss Ima Hogg, who had restored the Winedale property, including a historic stagecoach inn, and donated it to UT in the late 1960s.

Hogg directed Ayres to peek into the property’s old hay barn, with its clay floor and handcarved cedar beams. “I want you to do Shakespeare in that barn,” Hogg informed him, and three weeks later, Ayres brought his first class. Now, the Shakespeare at Winedale program is one of the leading Shakespeare-through-performance programs in the country, with UT students studying and performing three plays each summer. Ayres, a professor emeritus, founded and continues to lead Camp Shakespeare, residential summer camps for children ages 11–16 who perform an entire play at Winedale at the end of each session.

The Shakespeare at Winedale logo perfectly captures this long love affair between a poet and a place. Known as “Cowboy Willie,” it depicts Shakespeare wearing a cowboy hat and a bandana, chewing a piece of straw, a wad of chewing tobacco bulging in his cheek. A few years back, the program printed T-shirts that read: “Rich History. Vast Countryside. Family Feuds. Shakespeare would have loved Texas.”

No doubt. In the meantime, we remain grateful for the gift of his words and characters and the chance to bring them to life. To lift a line from the noble Moor Othello, who was likely the first Shakespearean tragic hero to grace a Texas stage: He hath done the state some service, and we know’t.

Clayton Stromberger is the outreach program coordinator for Shakespeare at Winedale.