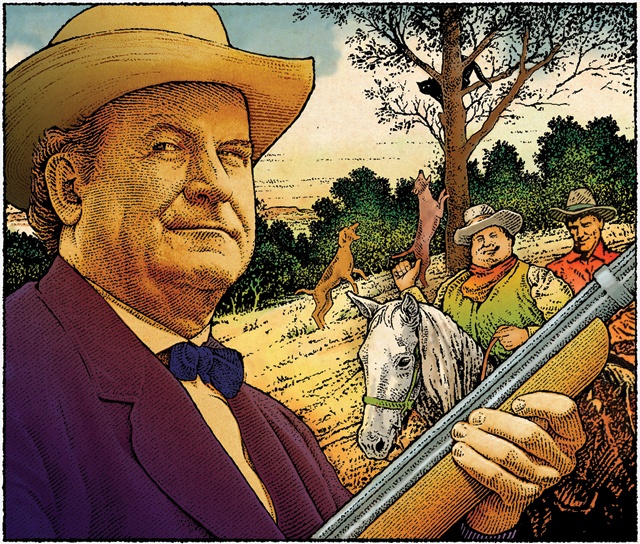

Whether a hoax served up for the newspapers or an elaborate practical joke on one of the country’s most famous politicians, the scene must have been something to behold. A hunting party of 100 men on horseback and 50 barking dogs set out from Austin to the hills—or “mountains,” as the newspaper tells it—west of the city on December 27, 1899, trailing a panther.

The guest of honor was William Jennings Bryan, who planned to secure the Democratic Party nomination for another run at the presidency. Former Gov. James Hogg led the hunters, his nearly 300 pounds astride a white horse, blowing away on his hunting horn as they headed into the rough country of scrub oak and prickly pear that lay between Austin and the little community of Oak Hill.

Hogg had been a strong backer of Bryan in the 1896 presidential campaign. Bryan also needed the support of Texas political kingmaker “Colonel” Edward M. House of Austin.

Bryan had been nominated in 1896, at the age of 36, a populist David out to slay the moneyed Goliaths, the northeastern bankers and hard moneymen who kept the farmers perpetually in debt. Although he lost to William McKinley, Bryan remained popular in his own Midwest and in what was then the solid Democratic South. Texas support was critical in regaining the Democratic nomination. Certainly for this reason, as much as for the mild winters, Bryan moved to Austin in November 1899 and stayed into April.

The day after the expedition, the Austin Daily Statesman reported under the headline, The Big Panther Hunt:

“They returned … with a live panther in their possession, having captured the same during the day. The … sport was reported as being quite lively throughout.”

Although the article hints that the prey was something less than a ferocious wild beast that had been “cooped up” and released as the hunters approached, the description of the hunt remains epic:

“The dogs took his trail at once, and after two hours rambling through heavy undergrowth and many acres of prickly pear came upon the panther, who had been forced to take refuge in a small tree. The dogs at once attacked him and during the melee several of them were knocked down … After about an hour’s skirmishing between the dogs and panther it was decided to attempt to capture the panther alive, and this was done by means of roping, and the beast was brought back to town in captivity.”

That might have been the end of the story, except as the years went by more details emerged. Bryan returned to Austin in March 1916, after losing the 1900 and 1908 presidential elections, to lecture at the University of Texas. The Austin American chose the occasion to recall the panther hunt with the added detail that the animal had been kept in a cage at a Congress Avenue saloon, where it was returned after the hunt.

Then, 24 years after the event and on the eve of yet another visit by Bryan, a letter appeared in the February 1, 1924, edition of the Austin American. The letter, written to Bryan by one of the hunt organizers, finally let the cat out of the bag, so to speak. The truth was that the entire incident was an elaborate, Texas-sized snipe hunt:

“After about a five-mile chase the dogs treed the panther and you all came up under the tree. There, upon a high limb, crouched the animal. Somebody, who was not in on the practical joke of which you were the principal victim, suggested that the cat be shot. Gov. Hogg and Weed objected however.

“Presently, you remember, that Gov. Hogg insisted in showing you some scenery nearby and led you away. When you came back the panther was gone.”

——————–

David Latimer is an Austin writer and instructor at Austin Community College.