Huntsville’s Lee Jamison has experienced art’s transformative power. In the 1980s he was teaching art in his hometown of Shreveport, a part of Louisiana he describes as “occupied East Texas.” A woman brought her teenage daughter, Kathie, to his class, hoping the artist might somehow rescue the young woman from a deep, dark depression brought on by an accident that left her with quadriplegia. “No request ever weighed more heavily on my soul,” says Jamison.

Web Extra: Evening Sun and Spanish Moss represents a composite from photographs made in Sabine National Forest, east of San Augustine.

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

After three weeks with no progress, the artist decided to try an experiment, painting with a semblance of the physical limitations experienced by Kathie. “I set up to paint with a brush in my teeth, my hands tied behind my back and my torso tied to the chair back by members of the class,” Jamison says. After three hours, Jamison had created two paintings: a simple seascape and a childlike sunflower under a sunny sky.

“That seemed to make a huge impact on Kathie,” Jamison recalls. “She became engaged in the class and signed up for more sessions.” In time she achieved a Bachelor of Arts and master’s degree and began work as a counselor at a local hospital.

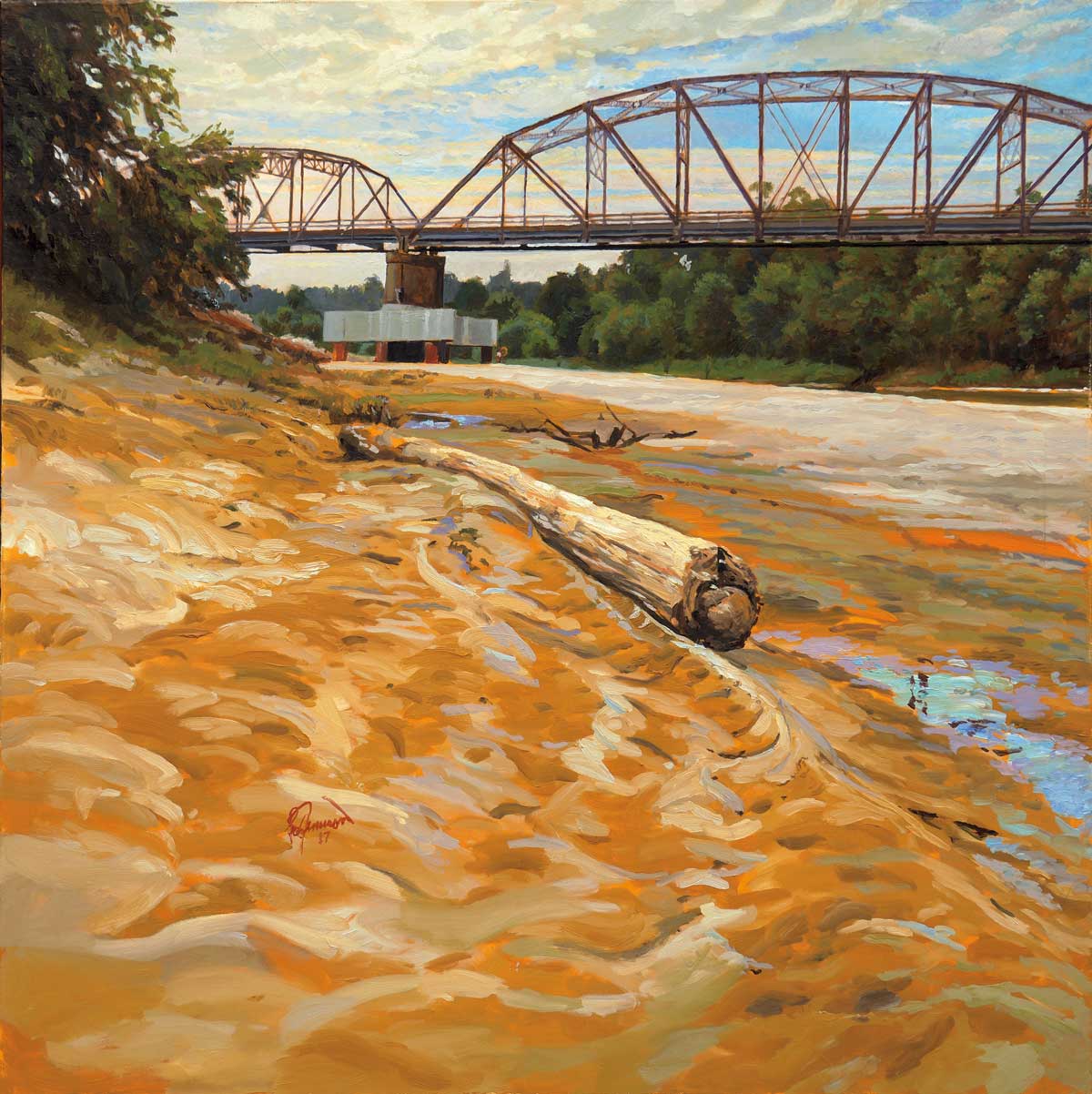

The Most East Texas: Burr’s Ferry Bridge, Sabine River shows the easternmost point in Texas, where Burr’s Ferry Bridge crosses the Sabine River as Texas Highway 63 becomes Louisiana Highway 8.

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

“Her mother thought I had hung the moon,” Jamison says. “Two little paintings helped her to separate the light from the darkness. How can I ever live up to the privilege of having been there to see that moment?”

Jamison answers that vexing question with each brushstroke in his Huntsville studio, creating paintings that help East Texans appreciate their region. His works depicting life and scenes behind the Pine Curtain gently lift a foggy haze that he believes has long obscured the cloistered realm. In Jamison’s view, to live in East Texas is, in many respects, “to disappear from the rest of the world.”

Connected, Downtown Lufkin, Texas shows the 100 block of West Shepherd Avenue in Lufkin.

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

Jamison got an eyeful of vanishing small towns, woods and prairies while attending Lon Morris College in Jacksonville in the mid-1970s. Singing with the college’s quartet, he traveled more than 10,000 miles for 111 performances. He continued to develop a deep and enduring sense of place when he moved to the Walker County hamlet of Dodge in 1984 and became a member of Sam Houston Electric Cooperative.

Though very few people appear in his paintings, local folks affected him just as much as did the landscape. “I need a human story,” he says, “to anchor a place—to make it real to me. Dodge is where I first thought of a field as having a personality and moods. There the earth itself seemed at times to become a part of me.”

Covered With Grace

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

Intensifying his regional experience, Jamison has painted scenes from the streets of Jefferson, one of Texas’ oldest towns, and the wilds of Sabine National Forest, Caddo Lake and the Big Thicket. Many of his paintings limn a distant past that still pulses through the region. A painting titled Journey to the Ancients depicts a dome-shaped grass house of the Caddo people built on a sapling frame. In a forested scene at Mission Tejas State Park included in the artist’s new book, Ode to East Texas, the artist works to encompass “the deeply rutted old path of El Camino Real,” one of many trails that followed “footpaths that had existed into darkest antiquity.”

Jamison has made more discoveries about East Texas since publishing his book in March. “Our region is really remarkably cosmopolitan,” he says. “It is full of well-educated, well-traveled people.”

Ghosts of the Atomic Age shows old trucks outside the Hilltop Icehouse in Point Blank.

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

More recent history is represented in paintings of the oil derricks in downtown Kilgore decorated for Christmas, the memorial for the New London school explosion of 1937 and a massive diesel generator that once powered the long-gone Love’s Lookout resort in Jacksonville.

Jamison’s canvases are comfortably yet dramatically readable. “People say I’m an impressionist or a realist,” he says. “I like to say I’m an abstract painter who makes his abstractions look like recognizable things.”

Web Extra: Isolation: Martin Dies Jr. State Park.

From Ode to East Texas: The Art of Lee Jamison | Courtesy TAMU Press

That perspective bolsters the mystical qualities inherent in the way Jamison depicts mist draping a stand of pines or shafts of sunlight assuming sculptural qualities. His paintings ask us to slow down and take another look.

“We normally fail to see past the veil of commonness,” he muses. But if we take our time, our best selves can discover the extraordinary in the ordinary.