It has been three decades since strife between Vietnamese immigrants and native fishermen shook placid Texas Gulf Coast fishing towns.

For some, that culture clash between newly arrived Vietnamese fishermen and the established fishing industry probably seems like yesterday. For others, it is a remote memory. The good news is that Vietnamese are now unquestionably a part of the larger community. Many coastal natives attribute this success to a cultural tradition that emphasizes family, education and hard work.

Leaving Vietnam

When U.S. military troops left South Vietnam in 1975, hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese who had fought with Americans against the North Vietnamese in the Vietnam War were prime candidates for reprisals. Many South Vietnamese escaped as best they could and scattered across the world. Some went to the U.S. immediately after the war. Next came waves of boat people from 1978 to 1990. This country began sponsoring an “orderly departure program” for Vietnamese who could find sponsors during the 1980s. And since 2000, Vietnamese have been able to come to the U.S. on student visas.

Vietnam is an S-shaped country with water to the south, west and east—the Gulf of Tonkin, the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. Many Vietnam refugees seeking a familiar landscape found their way to the warm sun of the Texas coast.

Early immigrants who took up fishing were welcome, but as numbers increased, Texas shrimpers, oystermen and crabbers, already territorial, became resentful.

The Vietnamese, many of whom didn’t speak English, were unfamiliar with established fishing protocols and unwittingly violated them. Texans, bewildered by this influx and unhappy about increasing competition, squabbled with the newcomers.

Tensions finally blew in 1981 when the Ku Klux Klan descended on the coastal hamlet of Seadrift. Vietnamese families were threatened, boats were burned, and an effigy of a Vietnamese fisherman was hung from a boat.

Federal marshals came in to calm the situation at the start of the 1982 shrimping season. Relations gradually improved with the healing power of time.

A second generation of Vietnamese residents remains in towns along the coast, but fewer and fewer of them are taking to the water—due, in part, to diminishing shrimp catches, escalating fuel costs, overseas competition and increased opportunity in other career fields.

Ho and Tammy Nguyen’s Family

Conversations with Vietnamese along the coast today invariably include the usual “firsts”: the first to attend West Point; the first to go to medical school; the first to play professional football.

The football trailblazer is Dat Nguyen, the former Rockport-Fulton High School and Texas A&M University defensive standout who starred at linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys as the first player of Vietnamese descent to compete in the NFL. Nguyen, now an assistant coach for the Cowboys, is the youngest of six children born to Ho and Tammy Nguyen. His roots extend from the village of Ben Da half a world away from Texas.

In Nguyen’s autobiography, Dat: Tackling Life and the NFL (2005, Texas A&M University Press), he writes about his family’s home along a small harbor near the Mekong Delta. Summers were miserable, not unlike those in Texas. As the war wound down and communist forces drew closer, Ho Nguyen and his extended family decided to leave.

At the time, Tammy Nguyen was pregnant with the son who would become a fearsome linebacker. They walked five miles through woods and along the coast to a fishing boat that was to ferry them to a ship and, ultimately, to safety. But they missed the boat and ended up in a camp in Thailand, awaiting dispatch to a receptive country.

Eventually, they made their way to the U.S., and after a brief stay on the West Coast, the family arrived at the Fort Chaffee military base in Arkansas in 1975. Dat Nguyen was born there that year on September 25. During the next year, the family zigzagged from Kalamazoo, Michigan, to Fort Worth, New Orleans and Biloxi, Mississippi, always in search of better weather and better lives.

They moved to Rockport in 1978 after hearing of good shrimping opportunities there. Ho and Tammy Nguyen worked before sunup and after sundown. With savings, they bought materials to build their own 47-foot trawler.

Today, Ho and Tammy Nguyen and their six children are engaged in fields far removed from the dangers and demands of shrimping. Most of the children are involved in the family’s five Hu-Dat restaurants that grew out of a small eatery near the Rockport waterfront where Tammy, the family matriarch, prepared Vietnamese meals for men who worked the boats.

Lyly

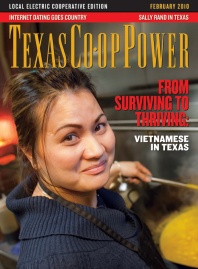

Lyly (pronounced “Lily”) is the oldest sibling and manages the popular Hu-Dat Noodle House in Corpus Christi.

“My aunt and mother did the cooking at the first noodle house. Area residents who weren’t Vietnamese became curious and started tasting our food,” Lyly says. “They already knew Chinese food so they thought Vietnamese food was the same. To get more local people interested in food, we started cooking with less garlic and fish sauce and lemongrass because some people considered the flavors too strong.”

The social climate has improved for Texas Vietnamese since Lyly’s childhood. “I grew up here and remember being picked on because I was Asian,” she says. “When I finished school, I moved away and lived in California for 10 years. When I came back, Corpus Christi was a different place. That was almost 20 years ago. I think people learned that we’re no different because of the color of our skin.”

The family now has restaurants in Rockport-Fulton, Ingleside and Portland as well as Corpus Christi. Each of the siblings manages restaurants except Dat.

Lyly, a diminutive, dark-haired dynamo, is in a constant state of alert as the phone starts ringing for lunchtime to-go orders on a weekday mid-morning. Making sure the phone is answered before a third ring, she catches an employee’s eye. He promptly lifts the receiver and greets the caller: “Hu-Dat Noodle House.”

Lyly greets some customers by name as she interrupts her conversation with a reporter, this time to help take orders behind the counter. The lunchtime crowd line is getting long now. Her smile is bright and genuine. Those she doesn’t know by name, she knows by what they like.

“You gonna do the pho bowl with beef today or you gonna try something different?” she asks a burly worker. “You know me too well, don’t cha?” he replies. He chooses his usual oversized bowl of pho dac biet, rice noodles, beef and beef broth. He pauses. “And give me two of those shrimp rolls, not the fried ones, the ones …” She knows what he means.

She nods and smiles. He nods and smiles back. She laughs. His smile broadens. She knows how to work her customers—in a good way.

The scene shifts at dinner. Workers are replaced by more families, older singles and a few young people clearly on dinner dates. Through a doorway and into the bar just off the dining room, businessmen are enjoying after-work drinks and an appetizer platter. Lyly finally relaxes at the bar with a tall glass of fruit juice.

“When we close I might have a cocktail,” she says. “Before that, too much to do. If I stop, I want to go to take a nap.”

Lynne Nguyen

These hardship-to-success stories repeat themselves with only minor variations: 31-year-old Lynne Nguyen and her husband, Phillip, co-manage Romantic Nails, an immaculate multi-seat manicure and pedicure salon in the La Palmera Shopping Center in Corpus Christi. Her family arrived in the United States in 1976, first living in Wisconsin, where her father rode a bicycle to his job as a janitor, even in the winter. Then the family moved to New Orleans where Lynne’s father worked as a butcher and her mother was a grocery-store bagger before landing a job at Café Du Monde. The family also lived in Michigan. Lynne remembers a time in Wisconsin when one hard-boiled egg seasoned with soy sauce and eaten with rice fed her entire family.

In 1997, the family moved to the Texas coast and eventually saved enough money to open a salon.

Dr. Tayson DeLengocky

Until recently, Dr. Tayson DeLengocky, an ophthalmologist who earned an undergraduate degree at the University of Texas and completed his medical training at the University of North Texas Health Science Center/Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Worth, frequented Vietnamese restaurants in Corpus Christi. His is a compelling story. His father, who worked as a secretary in the foreign affairs department for South Vietnam, gained political asylum in France in 1983. “We were in the second wave of immigrants who left some eight years after the fall of Saigon,” DeLengocky says. While he has settled in the U.S., the other members of his immediate family are still in Paris—except for a sister in China.

The youngest of four children, DeLengocky came to the U.S. on an immigration visa in 1990. He completed his Texas residency in eye surgery in Corpus Christi and in 2009 joined a practice in Peoria, Illinois.

DeLengocky recounts, “People went to different countries—Japan, Africa, Israel. In France you can have citizenship, but you are French only on paper. Here in America you can merge into the mainstream if you want to. You can achieve anything you want if you work for it.”

Father Hanh Van Pham

Such stories as DeLengocky’s are testimony to remarkable perseverance and resilience. Father Hanh Van Pham, who leads the 2,000-family congregation of St. Philip the Apostle Catholic Church in Corpus Christi, also has such a story.

He and the rest of his family have been in the United States since 1975, and they are scattered across the Gulf Coast, in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Father Hanh plans to stay seven more years at St. Philip, marking his 25th year in the priesthood, before returning to Vietnam to follow the teachings of Mother Teresa and work among the poorest of the poor.

“The people who come to this country are survivors,” he says in his almost whisper-soft voice. “We all have big families because you didn’t know how many the war would kill off. We help one another. We help ourselves. We save. When we buy, we pay cash.”

Once outsiders, those in the Vietnamese community have woven themselves into the fabric of coastal communities, just as they have in other parts of the country. Diane Wilson, a former shrimper who wrote An Unreasonable Woman: A True Story of Shrimpers, Politicos, Polluters and the Fight for Seadrift, Texas, witnessed Vietnamese refugees as they became part of coastal life. At one time, she says, hers was one of only two, maybe three, fish houses that would buy from Vietnamese fishermen.

“When the Vietnamese first came here, they weren’t all crabbers or shrimpers,” she says. “Some were scientists and teachers. Some became my neighbors. They worked incredibly hard and saved their money. They had what they called the Vietnamese village. You would see all these old trailers—I mean rickety old trailers where they lived. But when they decided to buy a house, they’d come with a suitcase full of money. Now they own their own homes. They own fish houses, too.”

——————–

Ellen Sweets has been a columnist for The Dallas Morning News and the Denver Post.