In many ways, Willis was on a roll at the turn of the 20th century. The International and Great Northern Railroad had rolled into the new town in the 1870s, allowing local growers to ship their products—especially timber and cotton—to faraway markets for the first time. Willis held several steam-powered saw and grist mills, two cotton gins, a brickyard, a saloon and gambling house, numerous grocery and dry-goods stores, schools and churches for black and white inhabitants, even a college. By 1890, it was home to 700 people—and growing.

The arrival of the railroad also opened up distant markets to another familiar product of the Old South: tobacco. The crop had been a cultural attribute among East Texas Caddoans and other Native American tribes for centuries. Early Anglo arrivals to East Texas brought along tobacco they grew for their own use, using varieties they knew “back home” in states like Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Some Montgomery County planters experimented in the 1870s and discovered that the East Texas soil and climate also could successfully grow premium tobacco. Success even included the esteemed Vuelta Abajo variety grown in Cuba, recognized as one of the world’s finest. Adoption of premium Cuban varieties got a boost when the U.S. imposed high tariffs on tobacco from Cuba, around the time revolution on the island disrupted the international cigar market.

Cuban Quality

With prized Cuban cigars hard to come by, planters around Willis launched the state’s first attempt to grow tobacco on a commercial scale. In 1891, local farmer John Blum had a good year growing the Vuelta Abajo variety using seeds brought from Cuba. With support from tobacco leaf packers and dealers in New York City and Florida, other growers hopped on the bandwagon and produced a bumper crop the next year.

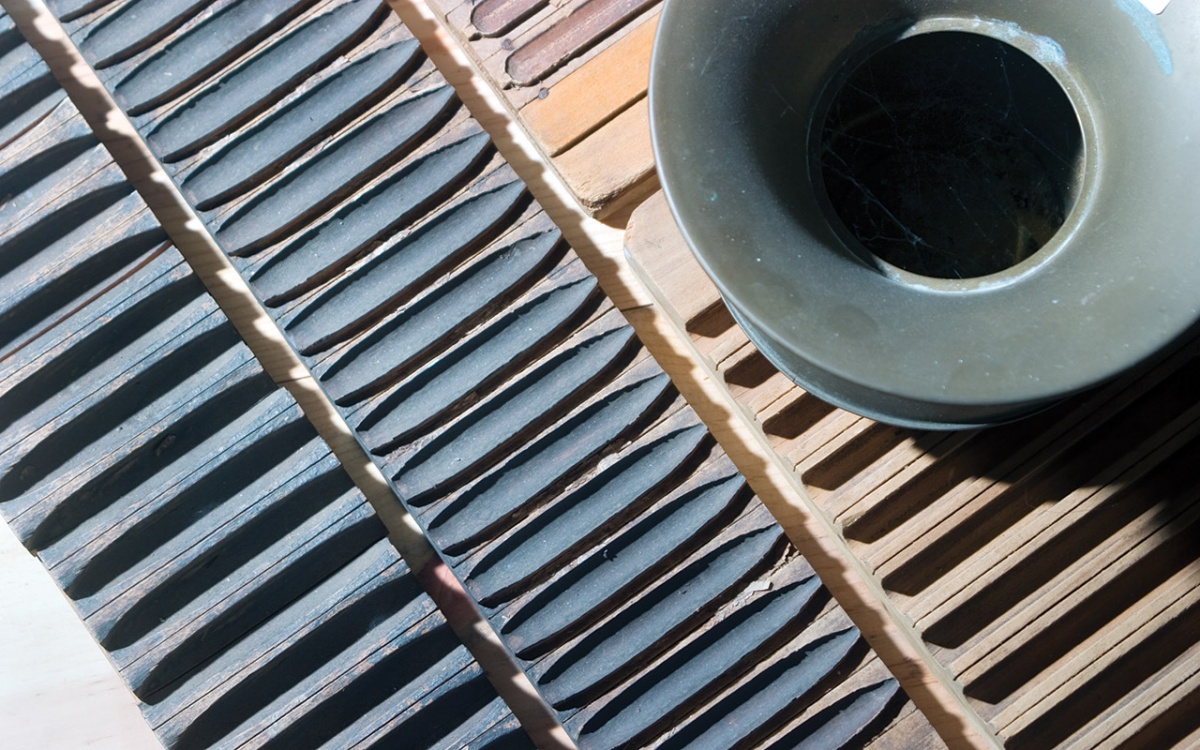

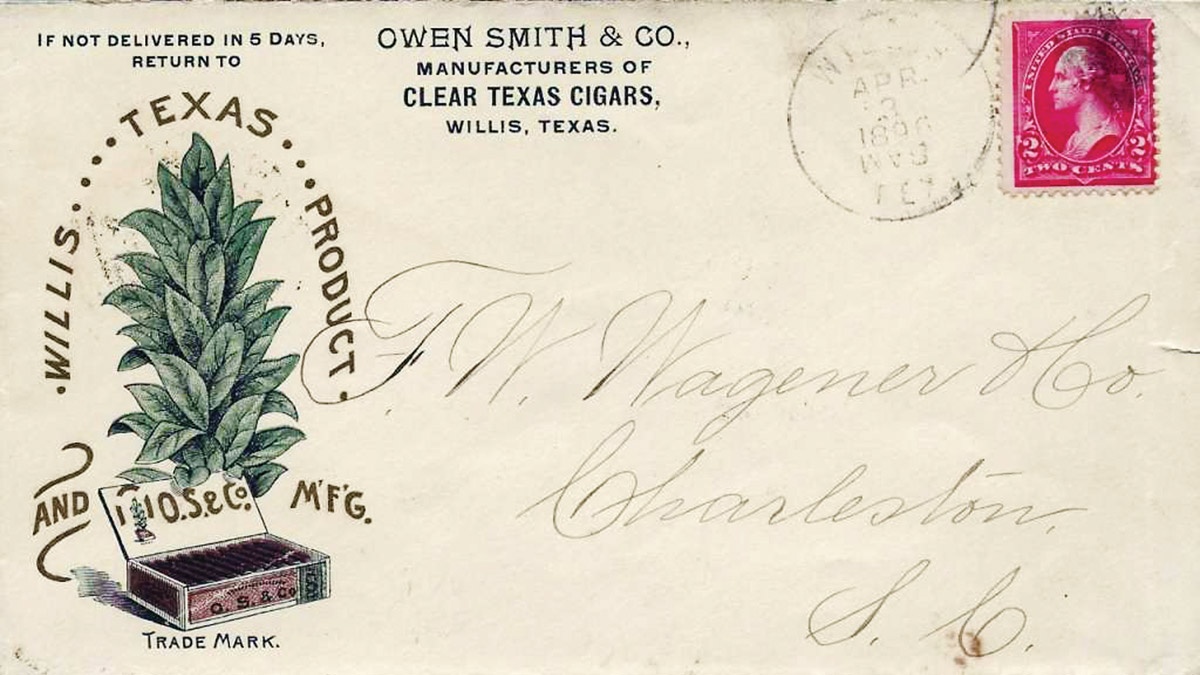

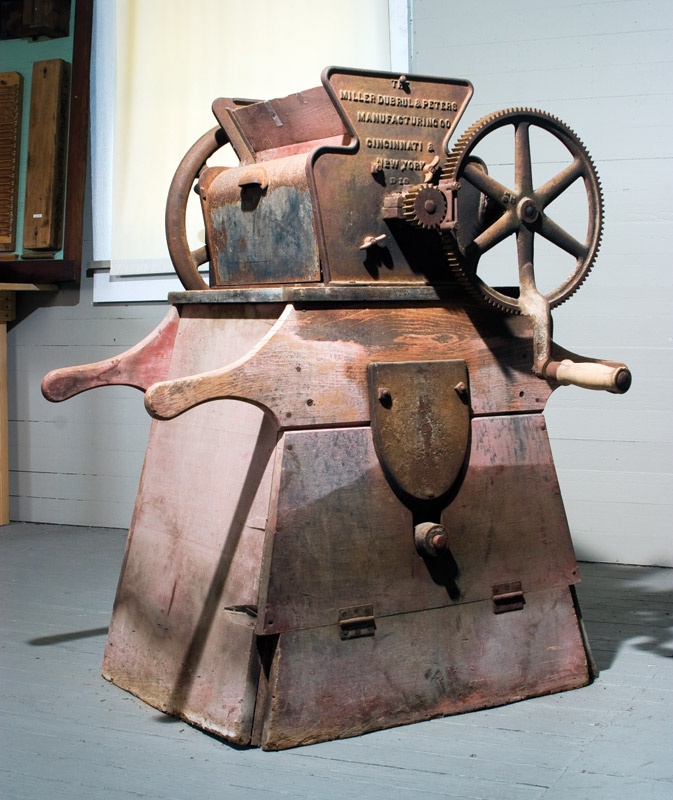

Tobacco barns popped up near Willis for drying the harvested bundles, or “hands,” of tobacco leaves. East Coast markets wanted a high-quality, Cuban-style product, so Willis manufacturers hired workers to hand-roll the cured tobacco into fine cigars. (Cigars were made entirely by hand until around 1920, when the first cigar-making machines appeared.) As many as seven cigar factories opened in Willis, transporting boxed top-quality cigars via steam-powered trains to Galveston’s busy port, where sailing vessels shipped them to U.S. and foreign markets.

For talented entrepreneurs, there was money to be made.

Most well-known among the Willis tobacco kings was Thomas Wesley Smith. The Kentucky native arrived as a boy in 1845, the year of Texas statehood. By age 21, he was elected Montgomery County sheriff, and after service in the Civil War, he settled into the mercantile business in Montgomery. The railroad bypassed his new hometown, however, and instead established a station at Willis. Smith followed the business and relocated to Willis.

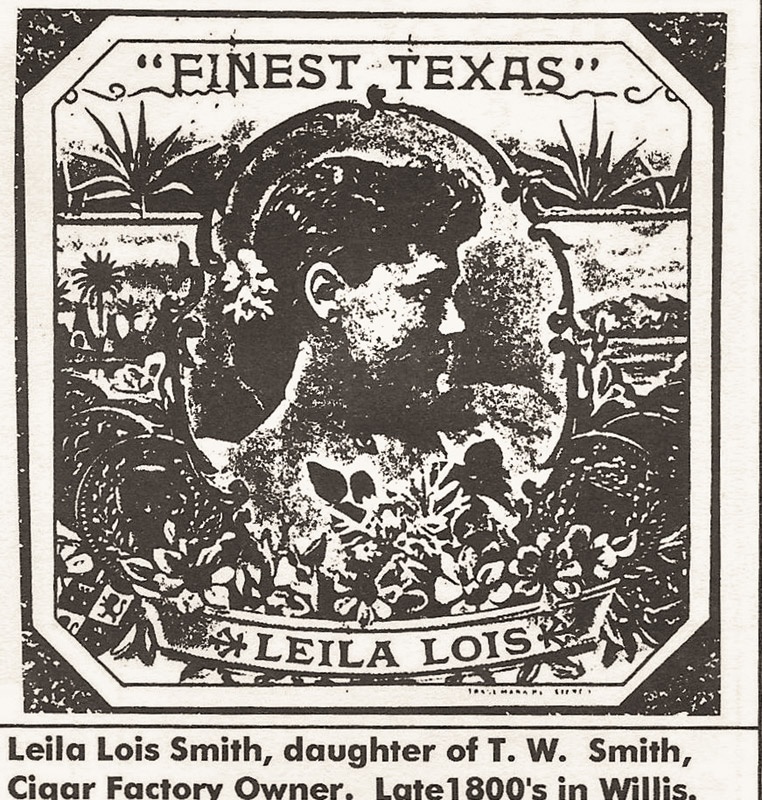

When the prospect of tobacco arose, Smith and son Owen went all in. They founded the Willis Cigar Factory, the largest of the town’s manufacturers. The imposing brick factory covered a large lot on Bell Street facing the rail line and employed some 100 workers. Cigar smoking was a widely accepted habit in the late 19th century, more widespread than cigarette smoking. So it was natural that Smith proudly displayed a photo of his daughter, Lelia Lois Smith, on boxes containing one of his more popular cigars. The family was somewhat scandalized, however, knowing that her picture would grace the interiors of “saloons and other places of ill repute,” said Smith’s grandson, Tom Smith, in a 1980s interview with local historians.

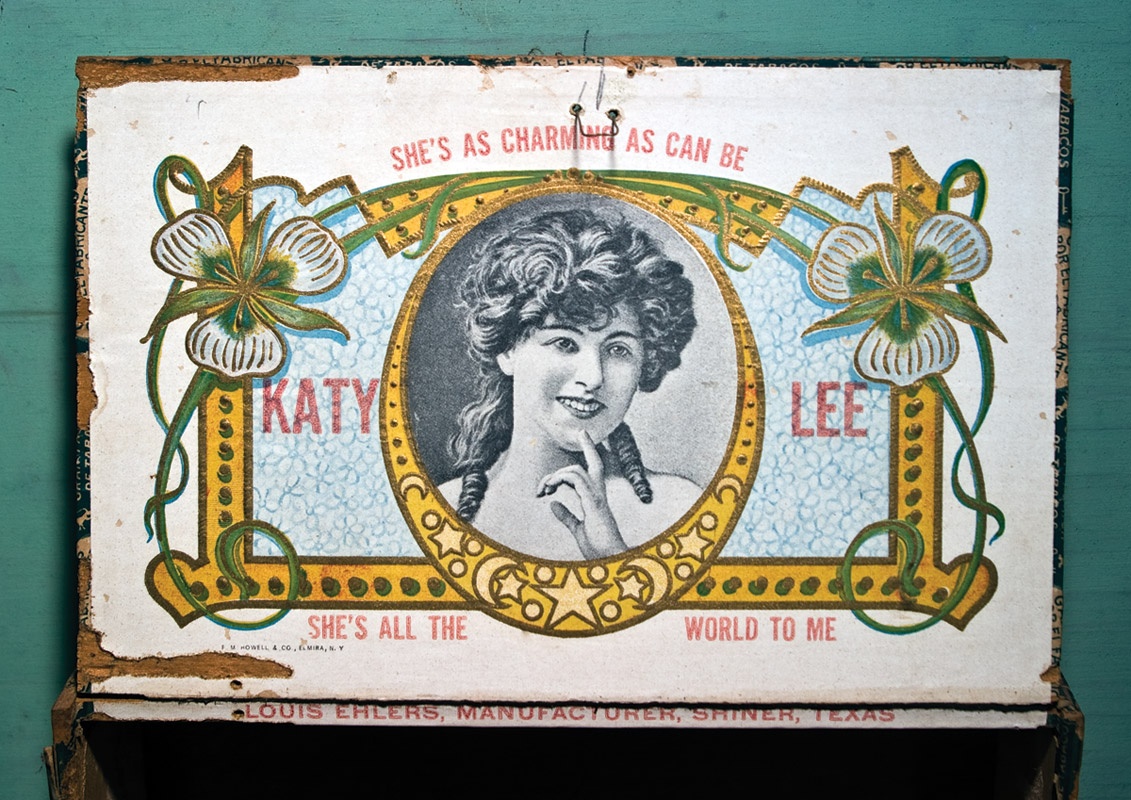

A few other Texas towns joined the cigar-making craze. In Shiner, part of the German-American area of south-central Texas, the Louis Ehlers Cigar Factory produced three popular cigars: the Becky Brown, Katy Lee and Good Company. The factory employed five labor union men who were paid 1 cent for each cigar they rolled. By 1900, Willis remained the mecca of Texas tobacco, cultivating as much as 1,500 acres within 5 miles of town. East Texas producers benefited from proximity to state prisons by contracting for low-cost field hands available through the state’s convict leasing system. On the heels of successful contracts with the Willis cigar manufacturers, in fact, the superintendent of Texas penitentiaries proclaimed the birth of a new industry, using inmates to grow Cuban-quality tobacco.

Hope for Prosperity

One grower, William F. Spiller, founded a town called Ada near his cotton and tobacco plantation 7 miles north of Willis. In 1898 or 1899, he changed the name to Esperanza (“hope” in Spanish), in hopes that his town and plantation would prosper. He built a 16-room mansion in the antebellum style of his Virginia birthplace. With 10 fireplaces and a metal roof, Esperanza Plantation was a showplace, says Willis historian Sue Ann Powell, who remembers the mansion from visits as a youngster in the 1950s.

“We took my grandmother to visit Mrs. Spiller,” says Powell, the great-granddaughter of pioneering Willis physician Dr. William P. Powell. “I recall seeing Spanish moss hanging from the trees in front of the fine old plantation home. Tobacco brought a very refined life to Willis.”

There was, indeed, good reason to hope for prosperity at Esperanza and other local plantations. Willis-area tobacco won first prize at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, then again at the Paris World’s Fair in 1900, Powell notes. Cigar magnate Smith stoked more civic pride when he built an opera house in Willis. But changing market conditions fizzled hopes for long-term tobacco riches. The Spanish-American War in 1898 temporarily halted political turmoil in Cuba, and the U.S. government dropped tariffs on Cuban tobacco products. Tobacco acreage in the Willis area dropped from 1,000 acres to just 70 by 1901.

In an attempt to revive Texas tobacco, the U.S. Department of Agriculture studied the region and estimated that 425,000 acres of East Texas could grow high-quality tobacco. The federal agency helped establish a demonstration tobacco farm in Nacogdoches and experimented with tobacco planting across East Texas. Tobacco packing houses popped up in Palestine and Nacogdoches, which also housed a cigar factory. (An old Nacogdoches warehouse has been restored as an event center, called the Old Tobacco Warehouse, in downtown.)

By the end of World War I, rising cotton prices lured East Texas growers away from tobacco. They also turned to truck farming, transporting locally-grown fruits and vegetables to a growing Gulf Coast market.

The once-explosive Willis tobacco business ended unceremoniously in what now seems like a vaudeville act. In an era of labor unrest, some disgruntled tobacco employees loaded gunpowder into some of the last shipments of Willis cigars, Powell explains. The Willis Cigar Factory building was abandoned by 1910 and burned by vandals in the 1930s.

“Tobacco was so instrumental in the growth of Willis,” Powell says, “that I hope more people will learn to appreciate this interesting part of our past.”