James Brown has a fascination with history.

For 23 years, the Texas native played the viola da gamba, a bowed instrument that resembles a cello but fell out of favor nearly 300 years ago.

“The whole thing was to put the listener in a time and a place,” Brown says. “When you’re hearing this music, if you closed your eyes, it’d be the same as being in Germany in 1735 hearing Bach conducting the chapel choir and orchestra on the same instruments.”

Brown specialized in music of that era, performed and conducted around the country, and was director of worship and arts for a church. But in 2016, he was looking into a second career.

Brown had been baking bread and pizza as a hobby (though he does have a culinary degree picked up among various music degrees). In pursuit of a better loaf, he happened upon a blogger in New Mexico who was touting the wonders of baking with locally grown grains from a co-op in Albuquerque.

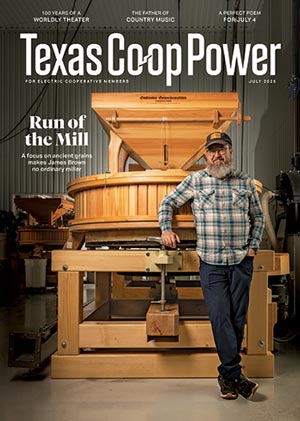

James Brown, owner of Barton Springs Mill in Dripping Springs.

Wyatt McSpadden

To his surprise, he couldn’t find a similar operation in Texas.

So Brown, who was living in Austin at the time, looked into establishing a small-scale mill that could process grains from local farmers. And, just as in his music career, he turned to the wisdom of the past, bringing those around him on a journey through time—this time by way of wheat.

Armed with historical documents detailing the grain varieties grown in Texas in the early 20th century and some hazy information about mills powered by Austin’s Barton Springs in the 19th century, Brown set out “to take people to a time and place” that no longer exists.

“What was growing in Texas? What were people eating? What was being milled in your hometown?” he wondered.

Brown got to work in 2017, and eight years in, Barton Springs Mill in Dripping Springs, about 20 miles west of Austin, provides freshly milled grains to a growing audience of restaurants, distilleries, bakeries and home bakers. It’s showing folks why they should care whether their flour is local and organic or an ancient, heritage or landrace variety.

Freshly milled grains are available for purchase on-site and online.

Wyatt McSpadden

The grains are selected with a focus on ancient varieties—those largely unchanged over time and still closely resembling how they looked and tasted before human intervention—and landrace and heritage grains—those developed in the 19th and 20th centuries, before more intensive hybridizing. Landrace grains are specifically adapted over time to the local climate where they are developed.

In addition to churning out flour, BSM offers tours of its 17,000-square-foot facility, which houses all the equipment to store, clean, mill and ship grains.

In a classroom opposite the mills, staff and guest instructors teach visitors to make breads, pastas and other baked goods. Through large windows in the classroom, visitors can watch the three stone mills.

The 7-foot-tall pine structures are fitted with a pair of 2,500-pound, flat composite stones. A pattern etched into the stones crushes the grain. The miller can control the result by adjusting the stones’ closeness, the speed at which grain is added and the speed at which the upper stone rotates. Power would have been provided by the water of a nearby creek a century ago, but today the mills get their energy from Pedernales Electric Cooperative.

The rumbling stone mills look like relics of the past. In some ways, they are. These days, most commercial milling is done with roller mills, which can produce flour much quicker.

Wheat sheaves from several heirloom varieties.

Wyatt McSpadden

Brown shows unmilled Sonora soft white wheat kernels.

Wyatt McSpadden

Brown’s goal is to show that flour can have its own incredible flavor and aroma. He wants the loaves of bread to transport them back in time, much like his music. Stone-milling preserves the germ and the bran, flavorful parts of the wheat kernel that are typically removed when milling white flour (though included in whole wheat).

“You pick up the aroma and the flavor and the characters of these wheats, and they become an equal player in anything that you make,” he says. “It becomes an ingredient that contributes those things, rather than just being neutral.”

TAM 105, a variety of hard, red wheat developed by Texas A&M University in 1976 and one of the mill’s more modern grains, smells to Brown like a wet dog while it’s being milled. Fortunately, that doesn’t translate when the finished flour is used for baking, and Brown recommends it for breads, pastas and pizza dough.

Barton Springs Mill’s warehouse. To keep the grain fresh in the Texas heat, oxygen is removed from each bag of wheat. Last year, the mill processed 650 tons of grain.

Wyatt McSpadden

On the other hand, rouge de Bordeaux, a 19th-century wheat, naturally smells and tastes of cinnamon, baking spices and molasses. “People will swear that’s in the bread,” Brown says. “No, that’s just the wheat—wheat, yeast, water and salt.”

Brown has gone to great lengths to track down seeds for wheat varieties he desires. He found farmers still growing marquis, which was popular in the U.S. in the beginning of the 20th century, in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Other seeds he could get only from the Department of Agriculture’s National Plant Germplasm System, a bank of plant material that conserves plant genetics.

When BSM was just an idea, Brown convinced 10 organic farmers across the state to meet with him. Over coffee or a meal, he presented his pitch: He’d provide the seeds and buy the wheat they produced. To his surprise, all 10 were interested, which meant he had to turn some down due to a lack of capacity.

Henry Martens has been growing wheat for Brown, in rotation with peanuts and cotton, at his farm in Tokio, about 40 miles southwest of Lubbock, since 2017.

A fifth-generation farmer, Martens always knew he wanted to farm. In 2015, when a piece of land became available that hadn’t yet been treated with chemicals, he couldn’t pass it up. He began organic peanut farming, which he rotated with cotton.

Today, Martens farms roughly 2,000 acres but likens his experience farming organic to tending a garden. The work is especially labor intensive—keeping up with weeds and caring for crops without the use of chemicals—but he says organic farming is worth it for him.

“It takes dedication and love,” he says.

When he met Brown, Martens had been looking to add another crop to his rotation. Crop rotation is particularly important for organic farmers, who rely on it to manage pests and diseases and keep soil healthy. Peanuts reintroduce nitrogen, a key nutrient, into the soil. Plant only cotton too many years in a row, and pests become a problem.

Wheat is a good rotation crop for Martens because it can be planted in winter, when weeds are less of a concern, and the tall grass provides cover to the ground, protecting it from high winds. As another plus, Brown pays his farmers significantly more for their crops than the market rate.

An additional benefit for Martens is getting to try the flour from his wheat.

“When you see it, it’s not what you’re used to seeing—the flour, where it’s so fine and perfect and white,” Martens says. “But I guess that’s never mattered to me and my wife. We care about it being organic and it being directly from the farm that we know, and it tastes amazing.”

The best way to test a grain’s flavor, Brown says, is to make a pancake with it. They’re simple, quick and allow the flavor of the grain to come through.

And since “nobody wants to eat a spoonful of flour,” Brown sends visitors next door to Abby Jane Bakeshop, which sells a variety of baked goods that use only BSM grains.

Brown is proud to help farmers, supporting what he calls the local grain economy. He works with four to five farmers each year (groups rotate in and out with their crops). Most are in Texas, but he has also worked with farmers in Oklahoma, Colorado and Arizona.

Brown says he gets a call from a farmer wanting to grow for him about once a week, but he’s at capacity. Last year, the mill processed 650 tons of grain. This year, it may take in a record 800 tons.

“I got into all this because I wanted a better loaf of bread,” Brown says. “That’s really the long and short of it.

“But along the way, I became more intimately acquainted with what’s going on with American farms and with American farmers and became quite passionate about how we treat farmers, regard farmers and our farmland.”

James Brown in front of one of his three mills, each fitted with a pair of 2,500-pound stones.

Wyatt McSpadden